The next time you travel through a city, see if you can find many four-, five-, or six-story buildings. Chances are, nearly all of the buildings you see will be either low rise (three stories or less) or high-rise (seven stories or more). If you do find any mid-rise, four- to six-story buildings, chances are they were either built before 1910, after 1990, or built by the government.

Before 1890, most people traveled around cities on foot. Only the wealthy could afford a horse and carriage or to live in the suburbs and enter the city on a steam-powered commuter train. Many cities had horsecars—rail cars pulled by horses—but they were no faster than walking and too expensive for most working-class people to use on a daily basis.

Most urban jobs were in factories and most factories were located in transportation hubs where the factories could get easy access to raw materials and easy shipment of their finished products. Single-family homes were not particularly expensive: a Chicago homebuilder named Samuel Gross sold them for under $500, or about $15,000 in today’s dollars—but building enough single-family homes for all of the factory workers in major cities would mean that some of those workers would have to walk long distances to and from work.

Mid-Rise Before 1900

The alternative was mid-rise apartments. Unlike high rises, mid rises did not require expensive construction methods and could be built with wood and bricks (“sticks and bricks”). Some residents had to climb four or even five flights of stairs to get to their apartments, but that would have been easier than walking an extra mile or two.

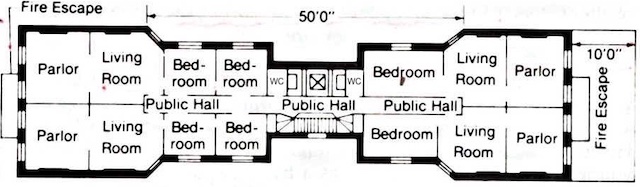

As documented in an 1890 photo book, How the Other Half Lives, the living conditions in these apartments could be pretty bad. Many were built with only two toilets per floor, with the intention that each floor would have four separate three- or four-room apartments. But sometimes families crowded into these buildings so that each room would house a single family, meaning a dozen or more families might share two toilets.

The floorplan of a typical New York City mid-rise apartment building of 1890. Notice that the public hallway extends deep into the apartments so they can be subdivided into smaller apartments.

These crowded conditions weren’t found everywhere and no doubt many mid-rises had, as intended, one toilet per two families or even one toilet per family. Still, quarters were small and noisy, privacy was minimal, and sanitation was questionable.

In 1892, the high-speed electric elevator was perfected by Frank Sprague, the same man who perfected the electric streetcar in 1888 and electric rapid transit, also in 1892. Rapid transit and streetcars made it possible for more people to live in single-family homes and elevators made people less willing to live in multi-story, walk-up apartments without an elevator.

Also in the 1890s, fire departments began to question the construction of wooden mid-rise buildings. Although wood was a strong enough material to support five-story buildings, those buildings could easily become fire traps, with a fire on one floor sweeping into the higher floors and trapping people from escape. Soon, fire codes were written to require concrete floors as fire barriers, and the extra weight of the concrete meant that mid-rise buildings required more steel. Add that to the cost of elevators and developers stopped constructing mid-rise buildings.

Read the rest of this piece at The Antiplanner.

Click here to download a five-page PDF of the policy brief (PDF opens in new tab or window).

Randal O’Toole, the Antiplanner, is a policy analyst with nearly 50 years of experience reviewing transportation and land-use plans and the author of The Best-Laid Plans: How Government Planning Harms Your Quality of Life, Your Pocketbook, and Your Future.

Nice hole-poking

in the New Urbanists' shorthand. It must be noted, however, that the war on "free" parking continues. Maybe the (unsubsidized) construction of parking garages goes a long way to properly pricing that privilege.