Andy Kunz of the U.S. High Speed Rail Association commented to Fox Business News on the recently announced record ridership on Amtrak that, "At the very least, the increased demand offers another sign travelers are getting fed up with soaring airline fares and fight cancellations." In the article, which read more like an Amtrak or high speed rail press release than a news story, reporter Jennifer Booton made what Gulliver, in The Economist, called "a fairly convincing argument that Americans are turning to trains as an alternative to driving and air travel." The Economist should have known better.

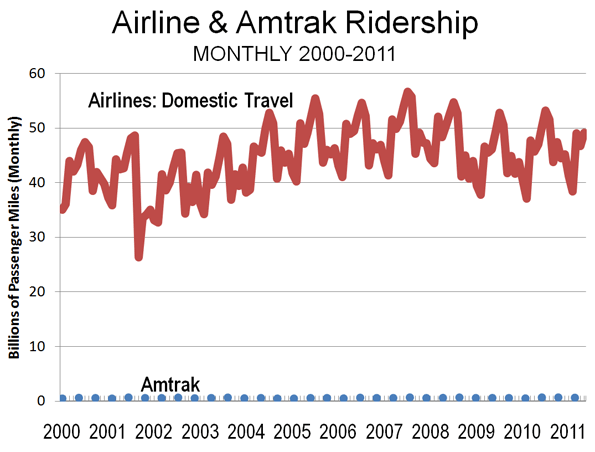

Yes, Amtrak ridership is up and airline patronage has been up and down in recent years. But, trains as an alternative to air travel? In fact, Amtrak's ridership is so small that distinguishing between the bottom of the graph below and the Amtrak ridership is difficult (see Figure). While Amtrak ridership rose five percent last year, the same number of new airline passengers would have constituted only 0.06 percent increase (or nearly 1/100th the impact on Amtrak). Amtrak's ridership is so low that the monthly change (increase or decrease) in airline patronage has exceeded total 2011 Amtrak ridership in 120 of the last 125 months.

Booton and Gulliver may imagine business travelers abandoning frequent airline service to board trains slower than cars that run once daily. Or perhaps they imagine faux-high speed rail service that will still be too slow or too infrequent. Airline executives aren't losing sleep over potential losses to trains.