The long awaited and highly touted Santa Monica extension brought an approximately 50 percent increase in ridership of the Los Angeles Expo light rail line between June 2016 and June 2015. The extension opened in mid May 2016. In its first full month of operation, June 2016, the line carried approximately 45,900 weekday boardings (Note), up from 30,600 in June 2015, according to Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) ridership statistics.

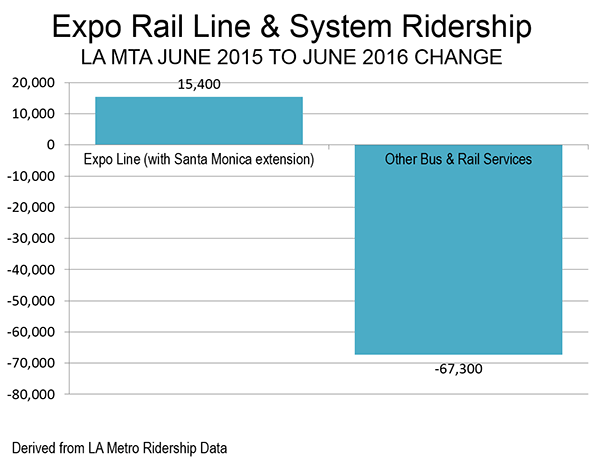

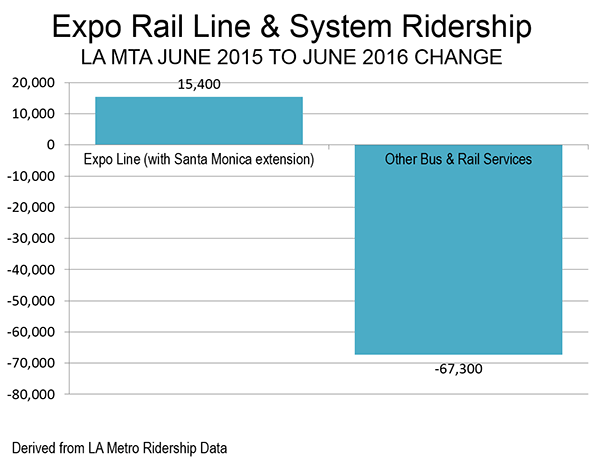

However MTA ridership continued to decline, with a 51,900 loss overall. Bus and rail services other than the Expo line experienced a reduction of 67,300 boardings (Figure).

Between June 2015 and June 2016, rail boardings rose 30,500, while bus boardings declined 82,400. In other words there was a loss of 2.7 bus riders for every new rail rider over the past year. Los Angeles transit riders have considerably lower median earnings than in the cities with higher ridership, and lower than the major metropolitan average (see the analysis by former Southern California Rapid Transit District Chief Financial Officer Tom Rubin and "Just How Much has Los Angeles Transit Ridership Fallen?" and ) here and here).

Note: A passenger is counted as a boarding each time a transit vehicle is entered. Thus, if more than one transit vehicle is required to make a trip, there can be multiple boardings between the trip origin and destination. Because the addition of rail services, as in Los Angeles, can result in forcing bus riders to transfer because their services can be truncated at rail stations, the use of boardings as an indicator of ridership can result in exaggeration, as the number of boardings per passenger trip is increased. This may have produced a decline of as much as 30 percent in actual passenger trips since 1985, as a number of rail lines have been opened in Los Angeles.