By Richard Reep

Investment in commercial development may be in long hibernation, but eventually the pause will create a pent-up demand. When investment returns, intelligent growth must be informed by practical, organic, time-tested models that work. Here’s one candidate for examination proposed as an alternative to the current model being toyed with by planners and developers nationwide.

Cities, in the first decade of this millennium, seem to be infected with a sort of self-hatred over their city form, looking backward to an imagined “golden era”. The most common notion is to recapture some of the glory of the last great consumerist period, the Victorians. During this time, from the 1870s to the early 1900s, many American towns and cities were formed around the horse-drawn wagon and the pedestrian. This created cities with enclaves of single-family homes and suburbs that seem quaint and tiny in retrospect to today’s mega-scale subdivisions and eight-lane commercial strips.

One bible for the neo-Victorians was “Suburban Nation,” a 2000 publication seething with loathing and anger over urban ugliness. In a noble and earnest effort to repair some of the aesthetic damage, the writers proposed a grand solution. Their goal was essentially to swing the development model back to the era of the streetcar and the alleyway, the era when cars were not dominant form-givers and families lived in higher density and closer proximity.

In the last decade, this movement gained traction with hapless city officials often tired of hearing nothing from their citizens but complaints over traffic and congestion. They embraced the New Urbanist movement which promised to turn the clock back to an era of walkable live/work/play environment of mixed neighborhoods. In the new model, the car would at last be tamed.

Yet, looking at most of these communities, the past has not created a better future. More often they have created something more like the simulated towns lampooned by “The Truman Show”. These neo-Victorian communities ended up with some of the form of that era, but devoid of employment and sacred space. They also created social schisms of low-wage, in-town employers and high-salary, bedroom community lifestyles marking not the dawn of a new era but the twilight of late capitalism as the service workers commute into New Urbanist villages while the residents commute out.

Meanwhile, planners who believe that practical design solutions and the vast quantity of remnants from the tailfin era are “almost all right” have remained quietly on the sidelines. This silent retreat, a natural reaction, now puts many good places in jeopardy as the activist planners try to “fix” neighborhoods and districts that were not broken to begin with. We risk losing some of the important postwar building form that well serves the needs of its users and, rather than being blacklisted, should be held up as a valid, comparative model for use by developers seeking to build good city form when the pent-up development demand returns.

It is time to hit back. Midcentury modern – the era from about 1945 to 1955 – has become a darling style of the interior design world, has yet to be recognized as a valid model for urban development. For too long, neighborhoods built in this era have been treated poorly by the planning community. Yet this period created a critical transition between the archaic beloved streetcar suburbs and the 1980s commercial car-must-win planning. They provide a valuable, forgotten lesson when the middle class’s newfound prosperity was expressed by low-density, car-oriented mixed-use districts that were still walkable and expressed through their form a certain heroic optimism about the future.

With building fronts set back just enough for parking, yet still close together to give a pleasant pedestrian scale, these little districts remain abundant in the landscape of our towns and cities – nearly forgotten in the fight over form, perhaps because they are doing just fine. They were built when everyone was encouraged to get a car, but before the car became a caveman club pounding our suburban form into big box “power centers” and endless, eight-lane superhighways of ever-receding building facades. These districts were developed before the local hardware store was replaced by Home Depot and many remain intact, thriving, and chock-full of independent business owners. Many of these are true mixed-use districts – with light industrial, second floor apartments, retail and other uses peacefully coexisting.

In small commercial districts developed in the late 1940s and early 1950s, a balance was struck between the traditional town form and the car, a balance that has been forgotten in the planning war being waged today. This era produced many neighborhoods and districts that are “almost all right”, in the words of noted Philadelphia architect and thinker Robert Venturi, when defending Las Vegas to the prissy academic community.

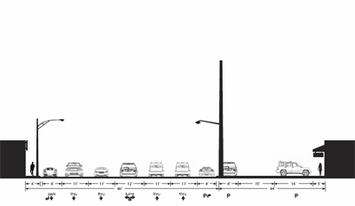

To go right to a case study, take the Audubon Park Garden District in Orlando, Florida. Adjacent to Baldwin Park, a Pritzker-funded New-Urbanist darling of 2002, this district is a vintage collection of mixed-use commercial, residential, and industrial buildings constructed in the 1950s. Set back from the curb approximately 42 feet, the mostly one-story storefronts allow parking in front yet are visible and accessible to pedestrians. The car is accommodated in the front of the store, making access easy and convenient, yet the pedestrian can walk also from place to place without long, hot trudges. Drivers see the storefronts. Scale is preserved. (See attached file for street elevations).

The architecture, instead of recalling nostalgic, Victorian styles, is influenced by the art deco and populuxe styles of the Truman era, when America was united, self confident, and victorious. And the businesses reflect an organic mix serving neighborhood needs, their storefronts and facades created by themselves, not by some Master Planner, theming consultant, or fussy formgiving designer. Here, one finds customers in dialogue with shopkeepers, blue collar and creative class mixed together, a few apartments over their stores, and a localism that has endured for fifty-odd years, largely forgotten because it works.

Places like this three-block district, and others like it, need to be championed. Decoding just what works here, and how it elegantly accommodates the car and the pedestrian, is critical to counterbalance the coercive impact of the New Urbanist movement and present a working model to future developers.

When New Urbanism was a fledgling movement, it represented a necessary alternative to car-dominated planning principles, and offered a choice where there previously was none. Today, the rhetoric of this movement has sadly forced out all other choices and emphasized one form – that of the streetcar era – over all others. This increasingly authoritarian movement shuts out all other choices today, and now threatens places like Audubon Park with its singular vision by sending in planners to “workshop” an ideal, Victorian makeover. Such actions, if implemented, will destroy the healthy, functioning connective tissue that makes up vast portions of our urban environment for the sake of a romantic notion of form over substance.

Instead of enforced, and often overpriced, nostalgia, we would do better to seek out districts planned after the car and have worked through time, and hold them up as valid choices to implement when planners are considering a development. These districts, whether a single building, a collection, or a whole community, will become important models as the pendulum swings back from the extremes that it reached by 2007 and 2008.

For too long, planners and developers have chosen to be silent in the face of the often strident rhetoric espoused by “smart growth” and New Urbanist ideologues. Meanwhile, a tough analysis of New Urbanism’s successes has yet to be seriously undertaken, and alternative models presented. Cities across the nation are considering a move to form-based codes which would lock out districts like Audubon Park and doom existing ones to Victorian makeovers. Useful, diverse and workable places will be destroyed to fit a “one size fits all” ideology.

So before midcentury modern becomes just another furniture style, a window of opportunity exists to fight back. These kinds of districts dot the cities and towns of America and deserve to be held up as alternative models for new development. Instead of a dogmatic slavishness to nostalgia, planners and developers need to stand up to the preachers of preapproved form, and look for multiple solutions for future urban form. Smart growth should not supersede the arrival of a more flexible, diverse approach of intelligent growth.

Richard Reep is an Architect and artist living in Winter Park, Florida. His practice has centered around hospitality-driven mixed use, and has contributed in various capacities to urban mixed-use projects, both nationally and internationally, for the last 25 years.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Audubon_street_elevations.pdf | 3.49 MB |

I went over this website

I went over this website and I think you have a lot of excellent information, saved to fav (:.

Hop Over To This Web-site

I love what youve got to

I love what youve got to say. But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better. Youve got an awful lot of text for only having one or two pictures. Maybe you could space it out better?

Go to First Finish Contracting

Diversity Design does alot

Diversity Design does alot more than just tattoos! They offer a variety of different services.

Interior Designers in Gaziabad

I am kind of late to this

I am kind of late to this party, but I think the author is setting up a straw man that is easy to knock down. Kind of like as if his only exposure to NU thought was USA Today. Not saying that's the case, it just reads that way. He's critiquing a caricature.

What?

I had to re-read your article. It just doesn't make sense. It seems like you just read about this stuff someplace, and created an opinion.

New Urbanism, is an alternative to car-centered development. This alternative is well overdue, and according to the values of properties affected, quite welcome.

Remember, in 1955, gasoline was 35 cents a gallon, and the roads were wide open. Driving meant freedom, independence, and discovery. Those days are quite over, the thrill is gone. Now, because of poor design, driving is virtually required. Driving is a form of slavery now, as we're dependent on $3 to $4 a gallon for gasoline, auto insurance companies, and pointless gridlock. The Automobile manufacturers are aware, of how the mindset is changing. They're making cars that look like cars of yesteryear, in the hopes of rekindling the fabricated passion of driving.

The truth about new urbanism, is not buildings, so much as planning. Here, much of the buildings are the same, it's the way the roads are designed, and the way that in-fill is placed that makes it more friendly to non-motorized traffic. You'll have to keep in mind, New urbanism isn't new here. We cancelled a number of freeways that were to slice up Portland, and spread sprawl out. Now we can bicycle just about anyplace, fairly quickly, and safely. The truth is, that pedestrian-centered development offers timeless appeal. We maintain an urban growth boundary, as a way to promote in-fill development, and preserve farmland and forests nearby.

Perhaps you can visit sometime. Just remember to tell everyone that it rains here constantly, we wouldn't want to break the image.

Credibility

Richard -

My reaction to your observations does not concern CNU, or the importance of the issues you discuss.

I'm far more worried about your lack of judgement - are you really holding this up as a good example?! Streetview confirms that this is a truly awful environment ... do you really think it is good for pedestrians? The existence of these environments should not surprise anyone, but to suggest that we use them as a model of some sort leaves me wondering who could possibly want to be a client of yours....

Tim Robinson

Architect & Urban Designer, Auckland, NZ

Excellent article. I've had

Excellent article.

I've had a long term problem with the so-called new urbanism, its facade of diversity and innovation, in what is essentially a conservative and dull design philosophy harking back to a quaint Victorian past. It reeks of religion, an unquestionable doctrine that the majority of planners and urban designers believe in uncritically.

Its such a contrived movement. I visited a new urbanist style development in Australia a few years ago, most of the land use was residential however they had this little stretch of retail premises on the ground level with apartments above. I think most of the retail premises were empty, there was simply not the critical population mass in the development and surrounds to justify the commercial premises. It looked like a movie set for some film shot in the Victorian era.

I have also long admired much of the immediate post war period suburbanism. Not all of it of course.

Like Reep, I am certainly no fan of much modern suburbia. I agree with him that the balance of some immediate post-war suburbanism is really good.

EVERYTHING is a contrivance

Not really arguing with your view regarding new urbanism, Matt, but everything we contrive today results from contrivances; each of us are nothing but contrivances and, of course, the auto-centric U.S. housing/transportation system as we know it today did not always exist and was itself contrived. “In 1949, President Harry Truman convinced Congress to break with the past and inject the federal government into the process of developing cities and financing housing. The 1949 Housing Act expanded the availability of federal insurance for home mortgages, igniting the growth of new suburbs farther and farther from the centers of our cities. Together with federal highway funds that came a few years later, the 1949 law started what we now describe as suburban sprawl."

And the whole FHA plus Federal Aid Highway Act (1956) what can only be termed “experimental contrivance” has always depended heavily upon subsidized contrivances (contriving schools on the fringe, contriving sewer and water lines to sprawling development, contriving emergency services to the fringe, and contriving direct pay-outs to developers) and has only been increasingly unsustainably contrived, especially beginning in the early 1970s (which is when the U.S. production of oil peaked, forcing us to contrive ourselves farther abroad).

If one mode of contrivance is so great, why can’t another be?

David Parvo

Most Senior Fellow

The Placemaking Institute

http://placemakinginstitute.wordpress.com/2009/12/16/contriving-multi-mo...

New Suburbia

Money.

In 1950-1970 the US was king of the world and the rest of the world's industry was in shambles. The US population was what 188 million? Young child bearing demographic with schools and universities the best in the world. In the 1980s-90s silicon and microprocessors added on where that industry was. In the 2000s debt on past success built some more. That built the cities and suburbs we have today.

In the end the city planners don't have the say of what gets built. Money does.

There isn't any money now.

The street view example you

The street view example you gave is downright dangerous for pedestrians. There isn't even a sidewalk and there's a ton of curb cuts:

Street View

The Audubon development appears to already have an alley in the back...You have given no logical reason why it needs a setback with parking in the front. Why not just move the frontage closer to the street, get rid of the curb cuts, add street trees, and have parking in the rear w/ the alley? This offers an incredibly safer environment for everyone (yes, cars will be safer too because turns would occur at intersections not randomly at multiple locations with makes people use their brakes) without banishing the automobile to the sidelines.

Sure, NU is very guilty of silly architecture from random time periods and often exaggerated down-scaling. There's much to criticize over NU, but this article argues for the very same thing with a nostalgic movement that occurred during a certain time period too.

A building with no parking on its frontage is not nostalgia, a movement, or even new urbanism -- it's architectural precedent that is seen throughout the entire world through many, many years.