The Virginia Department of Transportation does not like cul-de-sacs. You know, those little circles that suburban home dwellers worship so much and pay a premium to be located on? Under its regulations, all new subdivisions must have only through streets. Essentially, no more cul-de-sacs. Getting rid of these desirable dead-ends, according to the DOT, will improve safety and accessibility for emergency vehicles.

The new set of rules regarding street regulations is called Secondary Street Acceptance Requirements (SSAR). It requires a set of closed, interconnected street segments designed under specific formulae to make sure the streets are well situated for pedestrians and bicycles. The SSAR is also designed to better distribute traffic in local suburban settings, specifically subdivisions.

I’m here to defend the cul-de-sac, but not as it is typically built and designed.

What makes a cul-de-sac lot premium? Homeowners fall in love with the quiet courts and the sense of built-in neighborliness. The words "quiet cul-de-sac location" can spur more sales than the words "new granite counters." The homes have huge rear yards, because of the extreme pie shape. The paved dead end areas guarantee no traffic will be speeding through, making parents and kids feel safe.

The wide angles between the adjacent home sides create some useable side yard space, as well as added privacy. Quiet, serene, and safe – what’s not to love?

Who Determines The Best Street Pattern? One of the biggest problems of suburban street design is that those who typically plan subdivisions don’t focus on vehicular or pedestrian flow, nor are they required to do so. The vast majority of subdivisions (and even of master planned developments) in the US are designed by engineering and land surveying companies that focus on density and meeting the ‘minimums’. A developer will typically hire the same company that engineers and surveys their site to plan the subdivision layout.

Very little information is available on how to create suburban street patterns with connectivity. These areas may have significant topographic variations, making a traditional urban grid pattern undesirable. Suburban regulations don’t offer much help or guidance, either. Planning commissions and city councils that do not have an understanding of traffic engineering end up giving a yes vote to site plans they do not understand. The result is a conglomeration of people involved in the approval processes that produce a traffic system based more on familiarity than on functionality.

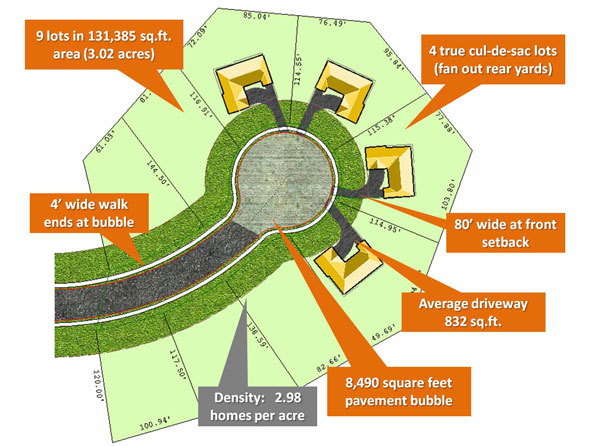

Cul-de-Sac Design Guidelines: To make matters worse, existing design guidelines for cul-de-sacs create the most waste with the least benefit. Here in the upper Midwest, a cul-de-sac will have a 120 foot diameter right-of-way with a 110 foot circle of asphalt. Why? Because fire departments say they need that radius to turn around a fire truck. Go a bit south and that dimension reduces to a 100 foot diameter right-of-way with a 90 foot diameter circle. I’m not sure why northern firemen don’t turn the steering wheel as tight as those in the South, but according to these regulations, they apparently can’t. So up North the typical cul-de-sac will consume 8,500 square feet of paving, and in the South just under 6,000.

This means that at a typical 25 foot setback from the right-of-way to the home front, an 80 foot wide suburban lot in the north will result in four or so premium lots. In the South, with a typical 20 foot setback and narrower 60 foot wide lot, there might be five or so premium lots.

An 8,500 square foot volume of cul-de-sac paving for four Northern-sized lots comes out to 40 percent more square feet of paving per house compared to the same lot on a straight street. This means the home will cost the city 40 percent more for snow removal, resurfacing, etc., forever. It also cost the developer 40 percent more, but that is recouped because the lots on the cul-de-sac can be sold at a huge premium.

A street leading to a cul-de-sac will have standard size lots fronting it. Depending upon the length of the street, there may be a few lots or dozens of them leading to the premium ones along the circle. These “street” lots might have a slightly higher value because of the low traffic approaching a closed end street, but they will certainly not equal the value of the lots around the circle.

From an efficiency perspective, it seems like only a fool would defend the use of cul-de-sacs. Here are some facts from that fool. In planning, everyone assumes that the minimum dimension is the most efficient. In cul-de-sacs, the minimum dimensions are typically very inefficient. Making cul-de-sacs larger than the minimum fire engine turning radius makes them more efficient.

Impossible? Take a look at the typical suburban design above, and compare it to to this re-designed cul-de-sac:

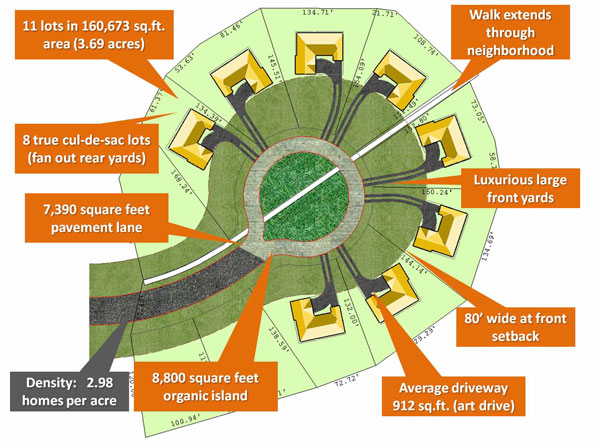

By making a typical northern cul-de-sac larger, say 160 feet in diameter, and using a one-way narrow lane with an island in the center, the amount of total paved area plummets. Instead of a solid sea of asphalt, the new cul-de-sac uses 10% less paving and has room for a central park that will be approximately 8,800 square feet of organic surface.

Now place the homes at a deeper setback. Yes, pulling the homes farther from the right-of-way to a 40 or 50 foot setback (instead of 25) accomplishes two things. It stretches the length of the setback line and makes the lots much less pie-shaped. The new, deeper setback should double the number of lots...with much less paving. Instead of being 40 percent less efficient, the new cul-de-sac is approximately 20 per cent more efficient than a rectangular lot on a straight street.

And while the new cul-de-sac lot is less pie shaped, it will still have a significantly larger rear yard. The lots overlooking an 8,800 square foot park will have a much higher value than if they were overlooking 8,500 square feet of asphalt or concrete. The park can be used in a variety of ways, but a combination of rain gardens and recreation seems natural. By draining into the center, we eliminate curbing on one side, making them even more efficient. Since the number of premium cul-de-sac lots is at least doubled and uses less paving and less overall land area, there would be fewer cul-de-sacs.

The Dead End Issue: But what of pedestrian and bicycle circulation? Well, that’s simple, as these non-vehicular designs can extend beyond the cul-de-sac as well as through them, making the central park areas destination places. Emergency vehicular access? Interconnecting walks could be made wide enough at certain locations to provide emergency access that would rival tight grid patterns.

If these arguments favoring the efficient new cul-de-sacs aren’t enough, God likes them! How do I know? What scripture did I study to make this claim? Well, if God did not want cul-de-sacs, then why vary the natural contours of the land? Not every site is perfectly flat or a perfect square shape. In many cases, contours form peaks and valleys in which cul-de-sacs may be the only way to design a development; anything else would be unnatural.

Hold your hand in front of you and then spread your fingers wide. When rain falls on the land and runs off it forms peaks and valleys similar to your jutting fingers. Where this happens, using the natural contour for the location of cul-de-sacs makes much more sense than trying to place a circulation pattern between the finger nails. Property configurations also often require a cul-de-sac or two (three, four or more).

Of course a big bull-dozer could reconfigure any land to implement SSAR, but then...wouldn’t that be a sin?

Rick Harrison is President of Rick Harrison Site Design Studio and Neighborhood Innovations, LLC. He is author of Prefurbia: Reinventing The Suburbs From Disdainable To Sustainable and creator of Performance Planning System. His websites are rhsdplanning.com and performanceplanningsystem.com.

Photo: