“Sponge cities” is an apt metaphor to describe urban communities in rural states like North Dakota which grow soaking up the residents of surrounding small towns, farms and ranches. North Dakota’s four largest cities, Fargo, Bismarck, Grand Forks and Minot, are growing in large part due to the young adults who for decades gone elsewhere to other regions. In the process, rural North Dakota is facing a protracted population crisis as significant numbers of its small communities are on a slow slide to extinction. This migration pattern is not new, nor is it unique to North Dakota. Historically, one of the most significant demographic trends in the United States has been the movement of people from rural to urban areas. In 1915 sociologist E.A. Ross declared that small Midwestern towns reminded him of “fished out ponds populated chiefly by bullheads and suckers.”

Beginning in the 1920s, North Dakota and South Dakota youth stopped wanting to step into their parents’ worlds. According to the Department of Rural Sociology, in 1927 more than 87 percent of farmers encouraged their children to go into farming, but by 1938 less than half of Dakota high schoolers were taking that advice.

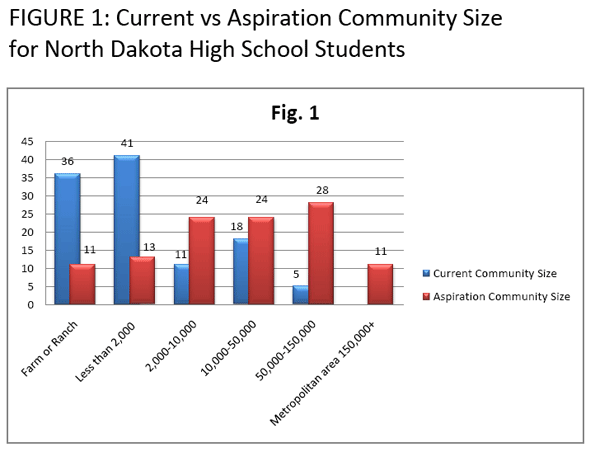

A June 2010 survey of 111 North Dakota high school juniors and seniors offers a glimpse into the minds of the state’s young adults as they stand on the precipice of adulthood. They were asked to choose the size of community in which they aspire to live and work. Although roughly four in ten were raised in communities of fewer than 2,000 residents, out of the over 100 students surveyed, only six wished to live their adult lives in the a town of fewer than 2,000. Overall, 70 percent aspired to live in larger communities than those of their childhood (see Figure 1).

Small towns struggle to provide urban amenities that can match the sponge cities’ bustling malls, skateboarding parks, concert venues and Olive Gardens. While the serene, friendly, stable rural communities, farms and ranches reflect the way that “life is supposed to be” in the minds of many outside the region, young adults often view that way of life as dull and sluggish. City life—albiet small scale by national standards—is perceived as fun, fast and fashionable; jobs pay better and there are more of them.

There has always been a desire among young adults to experience life outside of where they grew up. Experts believe that economics and quality of life are the two dominant motivations people have for moving from rural areas into cities. Mark Stephens, a young college graduate who left his small town of under 400 for Fargo, with a metropolitan population pushing 200,000, the largest city in the state, said “The first thing people throw out as an excuse is increased opportunity, but let's face it, 18- to 20-something adults are not thinking long term. For the most part, kids in that age group are really pretty shallow. In truth, I think it comes down to one word: Jealousy. They are walking down a gravel road in their tiny town with a link to massive amounts of media right in their back pockets. It's no different than when they were little kids—they see someone with ice cream and they want some too.”

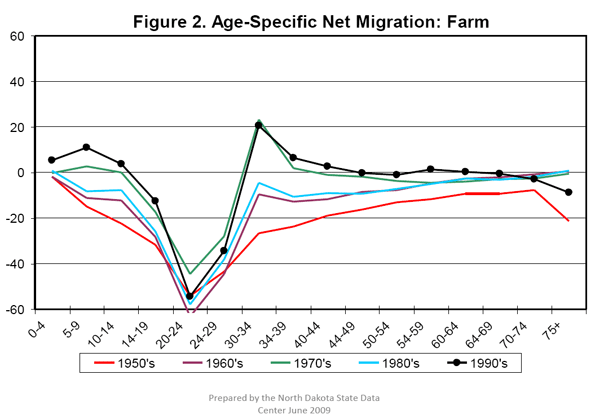

Richard Rathke, director of the North Dakota State Dakota Center, notes that aggregate data demonstrate the movement of young adults to larger cities in the Great Plains The young adult population (age 20-30) has been inmigrating to metro areas each decade since 1950 while in the farm dependent rural counties, they are outmigrating in sizeable numbers (see Figure 2).

A dozen young adults moving from Edgeley, North Dakota (population 637) to Fargo is irrelevant to Fargo as it absorbs the new residents with barely a nod, but to Edgeley, the shift represents significant and chilling loss of young, skilled, educated workers that will have a detrimental impact on the town’s future prosperity or even survival. Some predict that once Fargo has soaked up all the smaller communities, young professionals will then abandon Fargo for the more illustrious Minneapolis. North Dakota is touted in nationwide polls as one of the friendliest states in the nation, but schadenfreude flourishes on the Plains. Mayors of small towns that have lost their young people to growing population hubs have been known to remark, “Just wait until all of their kids move to Minneapolis.”

Perhaps metropolises like Minneapolis or New York will not be the ultimate sponge cities. Indeed, Minneapolis has experienced a 1.4 percent drop in population since 2000. Demographers are beginning to observe that for many of us there is a point where diseconomy of size becomes real. Traffic, congestion, housing prices, crime and pollution levels may already be curtailing inmigration to the nation’s major metropolitan cities.

The phenomenon of sponge cities will change the nature of states like North Dakota. At the turn of the twentieth century a mere 7 percent of North Dakotans were urban, by 1980 one out of every three residents was urban and in 2010 the state is projected to be 50 percent urban and 50 percent rural, a loss of nearly 88,000 rural residents in a state whose total population has remained stagnant, hovering between 600,000 to 650,000 for over a century.

A legitimate reaction to the entrenched loss of people from rural areas of North Dakota might be, “So what?” What does a state or nation have at stake in the health of a small town like Edgeley? After all, one community’s loss is another community’s gain. Migratory patterns are simply indicative of an efficient labor market; employers discover employees and employees find jobs that fit their skills, interests and education. Thus, one might conclude that is does not really matter if a significant percentage of rural Americans move to more urban areas. In fact, what some perceive as a seemingly endless stream of discouraging census data may actually be a positive indicator. Robert E. Lucas, Jr., University of Chicago economist and winner of the 1995 Nobel Prize in Economics, believes that a region’s successful transformation from traditional agriculture to a modern, growing economy depends on talent clustering—an accumulation of human capital that sponge cities are performing. The future may not be rural, but sponge cities could make traditional rural states like North Dakota very viable.

Wayne Sanstead, North Dakota’s State Superintendent of Public Schools and former lieutenant governor, has for decades watched rural schools close their doors. “We want the small communities to be a part of the state’s economic and social future, but we have to face reality and focus on retaining young adults within the state.” This may be the new reality. In large part due to the state’s booming economy, Sanstead asserts that in his 25 years as a state superintendent he has never seen a better opportunity then today for the state to retain its young people.

Deb Kantrud, Executive Director of the South Central Regional Council in Jamestown, North Dakota, has spent her entire career as a community developer. She noted that if small town residents stay behind after high school graduation, they aren’t considered as successful as those who relocate. We need to figure out a way to keep some smaller communities viable—turning them into sponge cities—while acknowledging that some smaller communities may not be part of the brighter future that awaits our reviving state.

Debora Dragseth, Ph.D. is an associate professor of business at Dickinson State University in Dickinson, North Dakota. She trains and develops leadership curriculum for CHS, Inc. a diversified energy, grains and foods company. The Fortune 100 company is the largest cooperative in the United States. Dragseth’s research interests include Generation Y, outmigration and entrepreneurship.

Excellent and very exciting

Excellent and very exciting site. Love to watch. Keep Rocking.

buy twitter followers with phone

Your content is valid and

Your content is valid and informative in my personal opinion. You have really done a lot of research on this topic. Thanks for sharing it.

facebook password online

Great to read

As a recent immigrant to North Dakota, this is great to hear. I love it here in Bismarck, but the city cares little for its built environment. Most commercial construction is corregated steel, most new neighborhoods are unwalkable, and hospital sprawl dominates downtown. If we truly began to draw young people, all that might change.

http://www.bismarckstories.com

A realist and then again, maybe not

“We want the small communities to be a part of the state’s economic and social future, but we have to face reality and focus on retaining young adults within the state.”

Maybe the focus should be on getting young adults to move into the state and not so much on retaining. This "She noted that if small town residents stay behind after high school graduation, they aren’t considered as successful as those who relocate." gets to the heart of the matter.

Encourage high school graduates to move away and then encourage them to return in their late 20s and early 30s to raise families.

Make the sponge city of Fargo attractive to the same age group across the country.

Dave Barnes

+1.303.744.9024

WebEnhancement Services Worldwide

P.S. Pixie is a cutie.