I’ve been spending a lot of time in Ravenna recently. No, not the town in Italy with its early Christian buildings and glittering mosaics. I mean Ravenna, Ohio, a small industrial city of some 12,000 people near Akron.

Along with Akron and Cleveland, Ravenna flourished as an industrial center in the early 20th century. In recent decades, however, its economy, like most of northeastern Ohio’s, has been sluggish at best, and the town hasn’t changed much physically for many years except for occasional demolitions at the center and new subdivisions at the periphery. News from Ravenna rarely makes it even into the Cleveland papers. It is certainly not known for its architecture. It has some perfectly good late 19th and early 20th century houses and commercial buildings, but none of these is likely to draw tourists.

One of the very few really remarkable things about Ravenna is a 150-foot high flagpole erected in 1893. Almost absurdly high for the scale of the city, it is a fascinating product of late 19th century American engineering ingenuity and vernacular design as well as a reflection of patriotism and civic pride. Standing right in the center of the city, it is arguably the most notable monument not just of Ravenna but for miles around.

Unfortunately, township trustees now plan to demolish it.

Image: Ravenna flagpole viewed from East Main Street, Ravenna Ohio. Photo by Tom Riddle, 2012

The battle over the Ravenna flagpole says a good deal about the fate of the great manufacturing belt that stretches along the southern edge of the Great Lakes. Once one of the greatest manufacturing regions of the world, it has struggled mightily since World War II as aging infrastructure, obsolete industrial facilities, a gap in educational attainment, and non-competitive wages have left it fighting to find its place in the late 20th, not to mention the 21st century economy.

In many ways Ravenna is a microcosm of the larger region. In Ravenna, as throughout the region, economic stagnation has taken a toll on the city’s built environment. Main Street has vacant storefronts and empty lots where stores used to stand. Some of the housing stock has started to deteriorate.

The biggest change in Ravenna, as in most Rust Belt cities, though, has been the transformation in the industrial landscape. In city after city from Duluth, Minnesota, to Rochester, New York, icons of American industry have vanished. The Homestead Steel works outside Pittsburgh has been largely demolished, replaced by a shopping mall. The same fate has befallen the LTV Steel plant in Cleveland and the great Western Electric complex on the boundary between Chicago and Cicero.

Image: Hawthorne Works Shopping Center in front of remaining tower of the Western Electric Hawthorne Works in Cicero Illinois

Some of this demolition was necessary, even welcome, since many of these factories were located amidst densely populated neighborhoods and constituted a logistical and environmental nightmare. But much of the demolition has been motivated primarily by a desire to remove from sight embarrassing reminders of a previous era. Demolishing the factory, city fathers figure, better allows potential buyers of the site to appreciate a wonderful riverside location or proximity to downtown and the endless opportunities to build something new.

What has replaced those grand temples of industry, however, has usually been underwhelming, with late 19th century brick loft buildings reduced to rubble to make way for cheap one-story strip malls that neither employ a lot of workers nor generate a lot of tax revenue. The old urban identity has been destroyed, but there has been very little to take its place.

The process is akin to the efforts of men and women of a certain age who resort to plastic surgery, hair implants and clothes more appropriate for a younger generation. These cosmetic efforts rarely fool anyone. In fact, what they most clearly convey is a loss of confidence.

Fortunately there is a growing awareness that wholesale demolition of industrial fabric does not necessarily prepare cities for their post-industrial future. This movement to save industrial heritage came into its own first in Britain, not surprisingly, since Britain was the cradle of the Industrial Revolution. For decades now important eighteenth and early nineteenth century industrial sites have been preserved, often as historic sites and tourist destinations.

Image: Ironbridge in Coalbrookdale, Shropshire, England, named a World Heritage Site in 1986

A similar thing has happened in the United States.

Image: Pawtucket, Rhode Island, Slater Mill, started 1793, now a National Historic Landmark.

Old loft buildings have become residential condominiums, even in some rather unlikely places.

Image: River Mill Condominiums along the Fox River in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, opened in 1986 in a building constructed for the Paine Lumber Company

Image: Quaker Square, Akron, a hotel developed in 1980 in concrete silos built by the Quaker Oats Company in the 1930s and now owned by the University of Akron.

The preservation of the industrial landscape that cannot be easily reused has been more problematic. Even so, there has been a movement to preserve some of the most important examples both as testimony to the industrial heritage of their regions and as a way of showcasing the regions in which they are located, providing amenities for the citizens and attracting tourists.

Germany has been a leader in this movement. The Voelklinger Huette outside Saarbrucken preserves an entire complex intact as a monument to the industrial heritage of the area. Even more spectacular has been the transformation of large pieces of the Ruhrgebiet, the heart of Germany’s pre-World War II heavy industry, into a set of imaginative parks, museums and other institutions.

Voelklingen Huette (Voelklingen Iron Works) near Saarbrucken, Germany. A UNESCO World Heritage site and museum.

Duisburg Nord Landschaftspark (landscape park) in Duisburg, Germany, a coal and steel plant transformed into a public park according to designs done in 1991 by architect Peter Latz who retained as many of the old structures as possible.

Of course, the Ravenna flagpole lacks the grandeur or the historical significance of these places. But it is an important historic relic in its own right and arguably as important for Ravenna as the great industrial complex at Duisburg is to the Ruhrgebiet.

Erected in 1893 by the Van Dorn Iron Works of Cleveland, the flagpole was one of at least four similar or identical structures erected in the northeast of the United States. It appears that only the one at Palmyra, New York, still stands. Recently refurbished, the Palmyra pole seems to have been built as a mast for displaying banners of political candidates.

Image: Post card of Main Street Ravenna showing the flagpole in front of the courthouse.

Image: Palmyra, New York, flagpole, fabricated, like the Ravenna pole, by the Van Dorn Iron Works of Cleveland. It has been recently restored.

These flagpoles reflect late 19th century American engineering ingenuity. Earlier poles had usually been of wood. They frequently snapped in high winds and had to be replaced. When the Ravennans needed to replace their pole they used a new and improved technology available to them.

The technology, involving the use of latticed steel boxes, was developed for the railroad and construction industry. The individual elements were not new. Steel had been replacing wrought and cast iron for a number of years. Truss bridges and other constructions using similar structural technologies had been well developed earlier in the century. Inexpensive steel and the techniques of constructing large structures out of it using rivets rather than bolts, however, was new. The technology was ideally suited to the construction of large structures of all kinds, notably bridges.

The same qualities of strength and light weight that made it ideal for bridges also made it perfect for towers. All over Europe and America engineers used latticed towers not just for flagpoles, for but lighthouses, look-out stations, electric light towers and a host of other uses.

Image: Electric Light Tower, constructed in 1881 at the corner of Market and Santa Clara streets in San Jose, California to house arc lights intended to illuminate downtown. It collapsed in December 1915.

Image: A surviving “Moonlight Tower” in Austin, Texas. Manufactured by the Fort Wayne Electrical Company for use in Detroit, 31 of the towers were purchased from the city of Detroit and re-erected in Austin. In 1970 the remaining 17 towers were listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The city spent $1.3 million to dismantle and restore these towers in the early 1990s.

Image: Villingen, Germany, Aussichtsturm (Observation Tower) 1888. This 30 meter high tower, erected on a hill outside the village of Villingen, provided views over the surrounding countryside as far as the Alps.

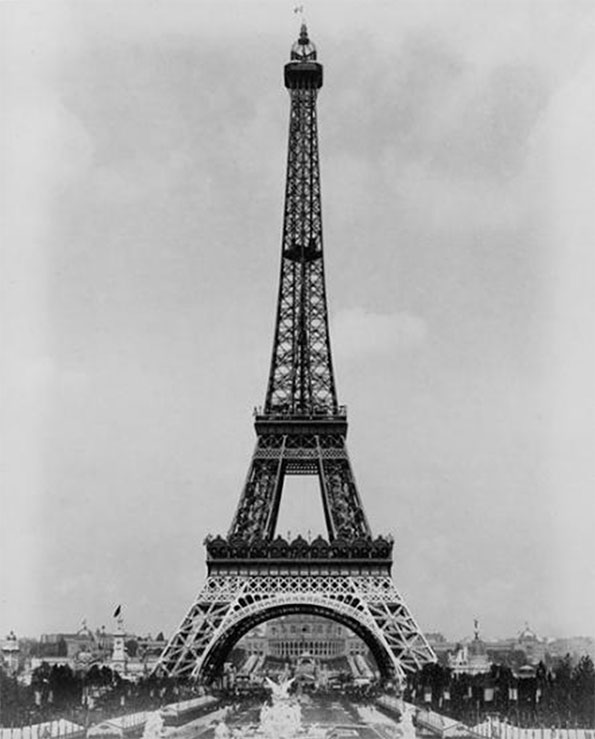

The grandest example of this structural technique is, of course, the Eiffel Tower, built for the Paris exposition of 1889. Although larger in scale than any of the other examples, it used many of the same materials and construction methods as the Ravenna flagpole. Initially heavily criticized by much of the artistic elite of the day as being essentially useless and much too big, the Eiffel Tower soon came to symbolize Paris to the world. No one would imagine demolishing it today.

Image: Paris, Eiffel Tower built for the 1889 Exposition. It reaches a height of 1015 feet using latticed steel elements and rivets similar to those used on the Ravenna flagpole

The Ravenna pole, erected four years later was built as a monument to national pride and an affirmation of the place of the city of Ravenna in the larger American republic. The pole also had a more local significance. It would allow Ravennans for once to greatly outstrip their neighbors and rivals in Kent, 10 miles to the west. In fact, at the time of its completion, the pole must have been one of the taller flagpoles in America and one of the taller structures anywhere outside the largest cities. Of course, by now it has been dwarfed, particularly in the last couple of decades when a new battle for flagpole superlatives has broken out, curiously enough this time in some of the most out-of-the-way corners of the globe.

National Flagpole at Baku, Azerbaijan, at 545 ft. flagpole, briefly the world’s highest flagpole before being eclipsed by one in Tajikistan. Both were built by a company in San Diego.

Even if now dwarfed by flagpoles in Azerbaijan, North Korea, and Tajikistan, the Ravenna flagpole still reflects the pride of a struggling industrial city. It has required periodic maintenance and has gotten into the news occasionally when some inebriated citizen has tried to climb it. However, for most Ravennans it has come to be so much taken for granted that citizens were stunned when they heard that the Trustees of the Township of Ravenna, the body that has jurisdiction, decided that it was a legal liability, a drain on township resources and should be demolished. In response, a group of local citizens has stepped in and is fighting to maintain the pole, raising money toward its repair and trying to see if ownership can be transferred to a governmental entity or group of entities willing to maintain it.

In one way, this is a fight about intangibles like local pride, patriotism, a desire to maintain historic heritage and a sense of place. Some people write off these sentiments as mere nostalgia. But preservation of this kind can have tangible consequences. No one is claiming that preserving the pole will generate vast new tourist revenues or solve basic economic problems. But the movement to save the flagpole rests on the notion that stewardship of historic heritage can play an important role in reminding everyone of the specific qualities of a place that made it successful in the past – and perhaps can be built upon to craft a better future.

Robert Bruegmann is professor emeritus of Art history, Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Historic heritage

Around the world we have found several cultural heritages. It represents the countries culture and traditions; here also we have found certain historic heritage in Ravenna, Ohio. Mostly in old cities we have found these types of historic heritages and it became one of the popular tourist's destinations. Countries like USA, India, Italy, France and others are basically known for best tourist destination due to their old heritage attraction.

Italian heritage festival

Great resources for ever

This blog is a great source of information which is very useful

fathers day quotes