There is a lot of speculation that residential real estate markets are in a bubble. Certainly there is cause for concern: The rates of gains in prices over the past year are unsustainable, and a bit disturbing. We are seeing multiple offers on a huge percentage of homes that are sold, and buyers are racing to make offers.

Sustained strong real estate markets are usually driven by household formation, or an increase in the percentage of the population that owns a home. Neither is happening.

Household formation drives a real estate market by increasing demand for modest homes and pushing existing homeowners up the ladder. It isn’t happening now because our young people, at the age when we would expect them to start households, can't do so. The economy has crushed them. They are unemployed or underemployed, burdened with college debt, and living with their parents. They will not be a source of strength for the real estate markets until job growth is far higher than it is now. End of story.

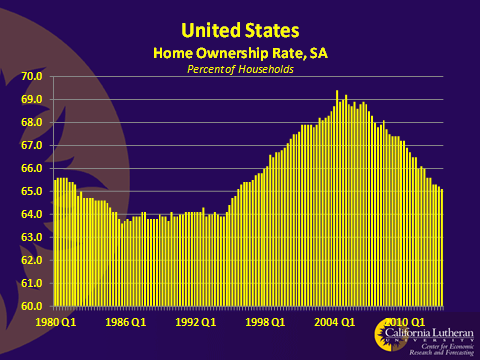

Home ownership rates aren't increasing either, thank goodness. Policy can only push home ownership so far, and then things go bad, really bad. A too-high home ownership rate was a significant contributor to our recent recession, and to its extraordinarily slow recovery. In spite of headlines, the continuing decline in home ownership is good economic news.

The home ownership percentage peaked at about 69 percent just prior to the recession. Since then, it's fallen to about 65 percent. Based on history, we think about 64 percent is a sustainable rate. Given the ongoing changes in how homes are financed, the sustainable rate may fall below 64 percent. In any event, growth in the home ownership rate is not and will not soon be a source of demand for homes.

Then there are the stories. We hear lots of stories about behavior that sound like stories we heard in previous bubbles.

Still, we don't think we're in a bubble. We'd prefer a more orderly market — that's for sure. We also don't expect to see continued price increases at last year’s pace.

The demand driving real estate markets comes from investors. This is something that had to happen. When the home ownership rate is too high, home ownership needs to be moved from unqualified residents to investors.

It took investors a while to see this, and government at every level did its very best to slow or stop the process. Eventually, though, investors couldn't continue to ignore the situation, and economic incentives overwhelmed government efforts to stop the process. Investors were flush with cash, and they had few alternative investments. Interest rates were at record lows, and home prices were low, often below construction costs.

So the investors stepped in, all at once, and in a big way. We've seen reports of some investment firms bidding on 200 homes a day in Florida.

You have to ask: How long can this go on? The answer is in the economic models used by investors. Their models look at interest rates, expected rents, capital gains, and price. Interest rates have ticked up, and markets are concerned about tapering of QE3. Still, we don't see any reason for a sustained significant upward move in interest rates. We also don't see any sign of a softening in rents, and thus the expect capital gains.

So, purchase price is the key to how long we'll see strong investor of demand. That is, given interest rates and expected rents and capital gains, there is a price below which Investors will purchase houses and above which they will not purchase houses. Call this the critical price. For simplicity, we're assuming — unrealistically — that all markets are the same. In reality, there is a critical price for every neighborhood or even every home.

The situation is clearly self-limiting. The investors all use very similar models. Once they hit the critical price, they will all exit the market. Since they are all using very similar models, they will all abandon markets at about the same time.

Then what happens? I think we'll have a new floor at the critical price. If the price falls, the investors will jump back in. Since we don't see any other strong source of demand, it's hard to see why the price would continue to increase above the critical price. So prices are likely to again be stable.

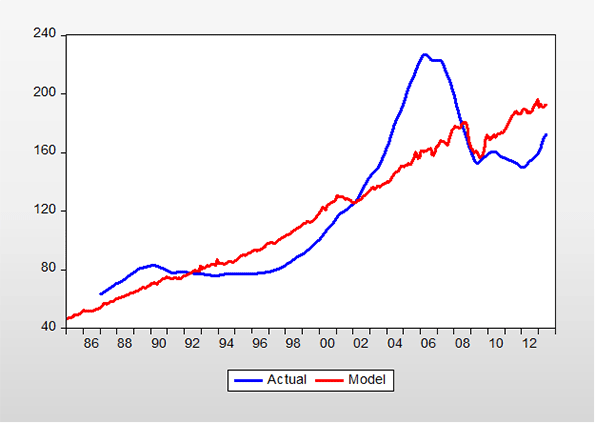

While investors do not always behave in rational ways — in particular they exhibit herd behavior — we are inclined to believe that they will not bid the price up significantly above a price supported by fundamentals: rents, interest rates, incomes, and the like. So, we built a simple model to see where we are.

Below is a chart that shows actual market prices based on the Case-Shiller survey, represented by the blue line, and our estimate of a price based on fundamentals, by the red line. According to this model, there is some room for continued gains:

That is not to say that prices couldn't fall. Our model is based on current economic conditions, and it is not forward looking in any way. If the fundamentals change, our model's estimate of value will change. Specifically, if interest rates increase or if income falls (because we go into another recession) we would expect to see prices decline. If job creation suddenly accelerates, we'd expect to see prices increase.

So, while we don't think that real estate markets are in a bubble, the current rate of price increase will probably not continue for long, either. The very good news is that, absent some unexpected negative economic shock, we don't see any reason for another price decrease within the forecast horizon.

Bill Watkins is a professor at California Lutheran University and runs the Center for Economic Research and Forecasting, which can be found at clucerf.org. A slightly different version of this story appeared in CLU Center for Economic Research and Forecasting's September, 2013 California Economic Forecast.

Flickr Photo by thinkpanama

Real Estate

That particular blog post is written artistically and it includes many practical knowledge for everybody. I guess you've carried out a great job of handling this delicate

Aggregate data doesn't tell the whole story

Yeah, but Bill, there are plenty of cities in the USA where house prices are anchored in "the cost of rural land" (i.e. $10,000 per acre) plus costs of development and construction, plus a modest profit in a competitive market.

What your analysis really needs to do, is divide the USA into the two separate markets, one where this is the case and the other where it is not, due to restraints on the conversion of rural land to urban. The perfect proxy for this is the Demographia Housing Affordability Reports. Extract one data set of cities with median multiples that remain stable at around 3 and below, and another data set for the cities where the volatility is.

This will provide a far more accurate assessment of what is really happened; aggregate data means that the stable price cities mask the volatility where it does exist.