This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism called "America's Housing Crisis." The report contains several essays about the future of housing from various perspectives. Follow this link to download the full report (pdf).

It is not primarily the fault of land developers that the American suburbs are thought to be dysfunctional and mundane. The blame belongs largely to the influence of boiler-plate zoning regulations combined with design consultants who seek the most minimum criteria allowed by city regulations.

Yet for all its problems, decade after decade 80% of new home purchases are not urban, but suburban. Some (architects, planners, and university professors) suggest we should emulate the dense growth of other nations not blessed with the vast area of raw land within our country, yet most of those countries as they prosper strive to emulate our American suburbs.

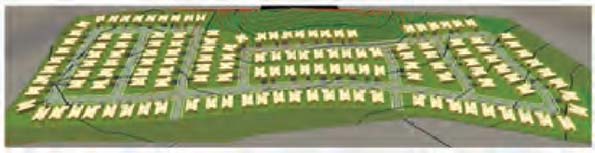

Figure 1 A model in the sales office of a new Suburban Development by AMARILO in Bogota, Colombia

The planning of our cities is about design. Yet, for the past quarter century a highly organized group consisting mostly of architects (acting as planners) have pushed a New Urbanist agenda that is as much about social engineering as it is design.

Their ’The Congress of New Urbanism’ (cnu.org) preaches of the world to come where all people of all races and incomes live in harmony along straight streets where densely compacted homes are aligned perfectly along a tight

grid. This ’New Urbanism’ is exactly how cities were designed before contemporary suburbia. In this sense they are not so much new, but as they themselves suggest “neo-traditional”.

Figure 2 A new development near Charleston, South Carolina using New Urbanism Design Methods

To convince others of the evils of suburbia they present the worst suburban examples lacking proper design as emblematic of their essence. Their solution is to forever banish suburban growth by whatever means necessary—usually through regulation --- that essentially eliminates choice for the consumer.

For most urban planning professors there appears to be just one singular solution: ever higher levels of density and a return towards the urban core. Young students study such models but, from my experience as a land planner, are grossly under-educated about what works in suburbia, where the majority of growth has been, and, short of a total political triumph of “progressive” planners or another catastrophic recession, will continue to take place.

One tragic result of this anti-suburban meme is that very little attention is played to how to improve suburban development, where design standards have stagnated since the mid-1950s. That is, until now… A new era of innovation made possible by technological advancements solves most, if not all, of the suburban growth problems, in a manner that deflates

the New Urbanist ’one solution fits all’ agenda.

DENSITY HAS NOTHING TO DO WITH DESTINY

Density is the most misunderstood and misrepresented excuse to attack suburban growth. Density and affordability are two very different concepts.

New Urbanists argue their high density solution allows people of all incomes to live in harmony, yet finding any affordable (non-heavily subsidized) dwelling in a New Urban development is highly problematic. The CNU boasts of their gentrification which by definition means upper income.

It turns out that diversity has nothing to do with ’design’ and everything to do with people wanting to live in neighborhoods with others, like themselves. Many conventional suburbs are far more diverse in terms of class and ethnicity than new urbanist communities, or revitalized parts of our downtowns.

Similarly, restricting how many families can be sardined into an acre of land (the definition of density) has absolutely nothing to do with affordability—if it did the New Urban projects would be the most affordable, not the most expensive.

New Urbanists are quick to point out the sprawl of new growth, completely ignoring today’s environmental restrictions. If cities of the past were designed using today’s wetland preservation (and buffers), shoreline buffers, slope restrictions, tree preservation, open space targets, and detention ponding, they would have sprawled also. Cities built with 2015 restrictions would likely consume 1/3rd more land area than if planned using 1915 restrictions. Much of today’s sprawl is due to environmental restrictions which have counter-productive side effects—higher housing costs, less convenience, and more commute time.

Those arguing against sprawl fail to recognize that a suburban land developer’s main goal is to maximize the number of units on their site, not build the least homes. Consultants hired by the developer assume maximum profit is achieved by the greatest number of homes, thus decreasing sprawl. If a developer could increase profits by proposing a 20 story multi-family building on their suburban tract of land they would seek an approval. But this runs up against demonstrated consumer preference: suburban dwellers do not commute to be on the 18th floor of a high-rise, instead they seek the most home on the largest lot within their budget.

However, a suburban problem is that higher density too often relates to ’cheapness’, and can result in unsustainable growth as characterless projects decrease in value over time.

Figure3 Unfortunately suburban higher density often equates to substandard housing as this example in Fargo, North Dakota

Developers will submit site plan proposals based upon market conditions. If the market desires large lots with estate-sized homes, that is what they will pursue. If the market desires dense single family homes with no usable yard squeezed in at six per acre that’s also what they will pursue.

However, because of possible forced regulations by New Urbanist, in some instances the developer may not have a choice but to submit a proposal with excessive densities when there is no market demand.

For example, in 2014 we designed a 60 acre site in Lake Elmo, Minnesota at a mandated high density. The city was forced by court order to adhere to density mandates of the Metropolitan Council, an agency who controls both transportation and sewer service for a seven county region surrounding Minneapolis and St Paul. In order to get approvals we had to design narrower than usual single family lots including high density multi-family.

However, the developer could not secure a viable multi-family builder as the market demand favored only single family. Luckily the site was located next to a medical clinic, so a high density senior housing building was proposed and was marketable, however, the single family homes would be harder to sell with a towering building in their immediate back yard. Other developers were forced to submit hundreds of multi-family units housing without residents to buy them.

That is why the New Urbanism movement and their Smart Growth agenda is so dangerous, they lead to instances where choice in density and in some cases design standards, is no longer a developer’s option.

IDENTIFYING ACTUAL SUBURBAN PROBLEMS

In most of the country, city regulations allow various uses (Land Use) be placed within a certain defined boundary or zone (Zoning). Each ’Land Use’ will have a set of minimum setback distances between structure and lot property lines for side, front, rear yards, and minimum lot size.

The problem with suburban zoning is that it encourages placing the highest density (the most families) in the worst locations, and the lowest density (least families) in the best locations. What constitutes the worst locations? Along noisy highways, behind loading docks of strip malls, and near loud railroad tracks. Somehow this ’transition’makes sense to City Planners who advise municipalities on growth.

Prime development land would have city water and sewer as well as provide great schools. For example, a non-serviced farm has low value, but when sewer service extends to the 80 acre corn field, developers are likely to come a calling enticing the farmer with a lucrative offer. After securing the land, the very next step is to ’plan’ the project

for submittal, most likely contracted with the local civil engineering firm.

In order to secure their lucrative engineering fees, the consultant offers to design a quick layout (typically for free) using the regulations most minimal dimensions to maximize the number of homes allowed on the site for a given zoning classification.

Figure 4 How ironic is it that placing high density in the worst location (overlooking loading docks) somehow makes sense?

Quality of living, vehicular and pedestrian connectivity, curb appeal, views from within the homes, and more are rarely implemented in the above scenario. Nothing in the cities minimums-based regulations require anyone to strive above ’average’! To make this bad situation worse, the ’planner’ of that 80 acres is likely to use an automated CAD software system to produce a site plan in minutes using preset configurations guaranteeing the cookie-cutter look of suburbia, thus what is called ’land planning’ is simply reduced to basic drafting geometry lacking any design sense.

Advances in technology have improved almost every aspect of today’s living—but for land development, current software solutions have done far more harm than good.

Unanimity in ideology, and lack of innovation prevented us from addressing how to improve the places where most Americans reside.

No universities concentrate on suburban design—only dense urban design. There’s little new knowledge about how to develop for the vast majority of people. Not surprising then, that a new development being proposed in 2015 is likely to be ’planned’ worse than one designed in 1955!

Today’s generations of designers (CAD operators) lack the passion to move the land development industry forward into a new era. We desperately need a properly trained new generation of consultants and architects who focus on how to make suburbs work better, more sustainably and, not to be forgotten, make a profit for the developers.

DESIGN CANNOT PROGRESS IN A NON-COLLABORATIVE INDUSTRY

For typical suburban and urban planning, a house is envisioned as a simple rectangular footprint only. The four main professions of land development design: architecture, civil engineering, land planning, and surveying tend to fail at both communication and collaboration, even when they all work for the same company. This problem is made worse by universities that teach multiple disciplines and enforce the barriers when students graduate. You would think architectural students would participate with engineering and planning students on the same projects to learn collaboration, but that is not the case. This lack of collaboration stagnates progress in land development.

A RECIPE FOR SUSTAINABLE GROWTH

’Sustainability’; that meaningless buzzword everyone uses on their company brochures generally avoids any real definition. Solar panels and rain gardens in inefficient neighborhood site design is hardly sustainable. However, if a developer builds a more efficient neighborhood that increases living quality maintaining its value and desirability over a long life span, it’s the definition of ’sustainable’. So, given all of the problems stated above—how is it possible to achieve it?

DESIGN FOR PEOPLE FIRST

Instead of using a software package to whip out a 200 lot site plan in less than 5 minutes, the land planner must place themselves in each and every home. They must imagine themselves in that space.

Figure5 A new suburban project near Tucson - what quality of living do these residents have - really?

The land planner must be passionate about those that will live in the neighborhoods they design and realize that their living standards, safety, and investment are strongly influenced by the planner’s efforts.

So we have to focus on very basic parts of what constitutes everyday life. What quality is the view from within the living spaces of the home? Does the street design allow a safe transit through the neighborhood maintaining traffic flow, or must the drivers contend with multiple intersections, sharp turns and pesky (trendy) roundabouts that only serve to increase both drive time and energy use? Do pedestrians cross at dangerous 4-way intersections and have only streets to walk near, or is there a dedicated pedestrian system that avoids conflicts with vehicles?

Are architectural details implemented to increase the beauty of the streetscape and to maximize the financial return for the residents? Will the neighborhood deliver a sense of pride at all income levels?

None of the above can be achieved by shoehorning in every home allowed by regulation minimums. It’s also not possible to reach those goals without a more collaborative relationship between the various consultants at initial concept design stage. No software program can automate any of the above. Professors need to teach good land planning design— not social engineering using methods of city planning from centuries ago.

THE MORE PROFITABLE SUSTAINABLE NEIGHBORHOOD

Putting people first seems like a noble goal, but won’t all that functionality destroy the developer’s profits and make suburban growth just as risky as the New Urbanism? The key here is to realize that to achieve higher profits and greater efficiency, you don’t have to change the regulatory minimums, but actually seek to exceed them.

Consider the following: Suburban planning and New Urbanism places every home at the most minimal setback guaranteeing monotony and restricting views from within the homes. Structures are placed as close as possible to the outermost boundary of a tract for densification. Streets parallel each other in a straight or curved pattern as the design of a neighborhood begins at the perimeter and builds inwards until all land is consumed. Thus ’land planning’ is reduced to simple geometry.

Unwittingly, this scenario not only maximized how many homes fit on the site, but also maximized the length of infrastructure (street paving, sanitary and storm sewer, utilities, sidewalks, etc.). The consumption of developed land typically forces re-grading (earthwork). Earthwork costs quickly destroy profits (not to mention trees, natural waterways, and any character of the existing land).

For centuries it’s been assumed that the most minimal dimensions were the most efficient way to design. A discovery make in 1988 proved otherwise. We discovered that separating the pattern of the homes front setback line (which typically parallels the street) with a different street pattern could maintain density while significantly reducing the length of street for any given set of minimums. The discovery was unintuitive—simply provide more than the regulatory minimums and efficiency is gained—not lost!

The resulting streetscape created a park-like setting with undulating open spaces in ’coves’, thus we coined the term for the method: Coving. This initial discovery led to scores of innovations that solve most suburban problems deflating arguments against suburbia.

We designed over 1,000 neighborhoods in at least 47 states and 18 countries contracted by over 300 land developers, those who desired to advance both suburban growth,as well as those involved in urban redevelopment.

EXAMPLES OF FUTURE SUBURBIA BEING BUILT TODAY

The following neighborhoods will help explain the benefits of the many innovations that grew out of the discovery of coving.

Example #1: The Enclave of Westpointe - New Braunfels, Texas

Below is the actual approved ’before plan’. With changes in water detention mandated by the city, there was 136 lots and 7,461 lineal feet of public street. There was 19 lots adjacent to the 7 acres of park. The typical lot was 8,000 square feet.

Figure 6 The original APPROVED plan for The Enclave at Westpointe

No developer or city would question the efficiency of the above design.

However, there is an enormous amount of waste in the design. Did you instantly recognize it? Neither the designer nor those at the city saw how wasteful the design is because recognizing unintentional design waste is counterintuitive and certainly not taught in planning schools.

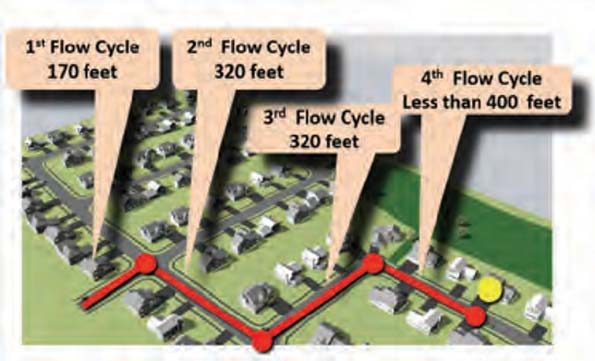

What about travel to and from most of the homes? One of the discoveries was due to research in traffic flow. Newton’s law: A body in motion tends to stay in motion. To get that body in motion (your car) takes an enormous amount of energy to reach the 25/30 MPH typical of residential streets and each stop repeats the waste. This process of acceleration to efficient cruise and stop will consume 400

feet and take approximately 20 seconds (called a ’flow cycle’). The drawing below proves for most residents the multiple intersections they encounter destroy flow. What at first looks efficient… is not.

Figure7 Short runs with stops and turns destroys f low and wastes both time and energy

Still trying to see the waste? An efficient street has homes that front both sides, but on the above plan much of the street is consumed by side yard. This waste consumes available land with Right-of-Way and pavement, thus to maintain density the smallest possible lot must be designed. Now look at the reapproved redesign:

Figure8 The After Plan of The Enclave at Westpointe

The redesign has only 4,973 lineal feet of public street reducing the infrastructure by 33%, or approximately $300,000 less construction costs. The original plan had only 19 premium lots (abutting open space). The redesign has 85 lots backing into open space (all lots are more premium), resulting in $600,000 in added value. The 136 lots average 9,395 square feet (15% more than the original typical lot), and a savvy engineer would have easily reduced both storm sewer and earthwork costs. The streets ’flow’ reducing time and energy while the wide elegant meandering walks invite a stroll. The city wins with 33% less maintenance costs and a higher tax base, the developer benefits, but most importantly the people investing in living in the neighborhood and those they will eventually sell to also benefit.

Example #2: The Sutherlands - Louisiana

This site is both long and narrow, never a good combination to design a good site plan. Most land planners simply squeeze lots to the most minimal depth to maximize density:

Figure9 The original plan for submittal for The Southerlands

The above site plan has 91 lots requiring 5,200 feet of street (just short of a mile). At the time of this writing a lineal foot street infrastructure in the Lake Charles area was $600. Thus about $34,000 in infrastructure alone per lot, not including the cost of the land or site grading (earthwork). Because of the tight distances at the entrance, the previous planner decided to place the smallest lots at the entrance cheapening the image of the development at the most important spot—the front door. The above plan lacks any sense of arrival.

The discovery of coving made it possible to rework even the most difficult of sites into a better place to live as seen below in the approved new neighborhood design:

Figure 10 The resulting redesign was approved in less than 2 months!

The new redesign creates a sense of arrival which continues all the way through the back of the neighborhood. The wide walks at the end of the cul-de-sacs are designed to handle emergency vehicles providing alternate access without having to build excess streets, while also providing increased pedestrian connectivity.

The oversized cul-de-sacs contain parks in the middle and towards the end of the road is a split island that adds landscaping and park-like space. You may think that all of this would be far too expensive to build. However the length of street plummets to 3,999 feet and there was a gain of 8 lots while also eliminating the low value miniscule lots at the entrance. The length of street suggests a construction savings of $720,000 the oversized cul-de-sacs as well as the elegant street island and wide walks serving as alternate emergency access does add some costs. The increase of 8 lots goes directly to the developer’s bottom line, however, and the added tax base to the city with reduced ongoing maintenance costs is of great advantage for the municipality.

Figure 11 Beauty and space is no longer a privilege of the wealthy

The residents all live in a unique elegant estate-like setting with large yards and great views from within their homes. The park-like streetscape with the wide meandering walks and even wider trails invite a stroll.

Both examples used coving to maintain street frontage along the setback line while reducing the length of street and related infrastructure.

Coving allowed (for the first time in the history of planning neighborhoods) compliance with existing regulations by exceeding minimum expectations and reducing construction costs, all while providing more space for homes at an equal density compared to conventional land subdivision. The cost reduction for site construction allows more funds to be used in other aspects of the development such as architectural detail, insulation, windows, landscaping, and as in the case of The Sutherlands creating landscaped islands to add neighborhood character and interest.

Example #3: Sundance Village— Dickinson, North Dakota

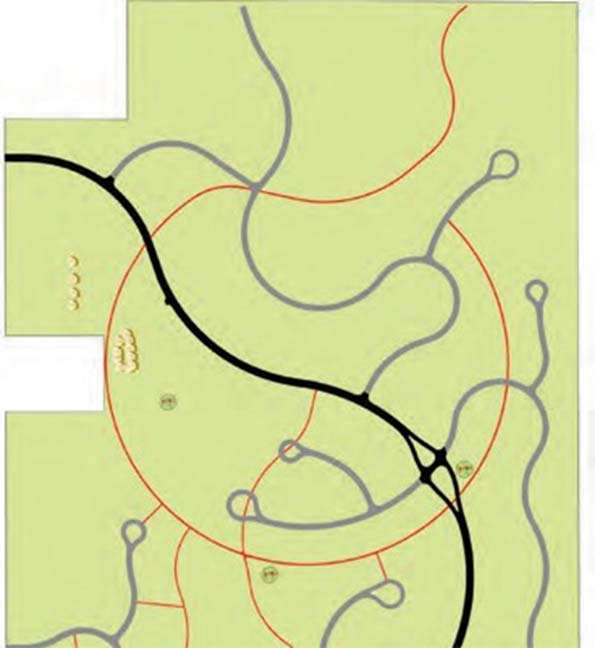

Figure 12 The 305 acre Sundance Viallge showing main circulation

FIgure 13 Sundance Village Linear parks & cascading ponds.

This next example is of a larger community. The last two examples were small sites explaining basic premises of this new era of design on relatively flat tracts of land. The same concepts to reduce infrastructure, maintain flow, and provide pedestrian connectivity scale up and down as the available acreage changes.

Larger sites can create more function and variety as well as more opportunity. This 305 acre site will house almost 1,000 families and provide a variety of services within walking distance.

The plan above shows the main trail interconnections (red) as well as the major internal streets (black) and minor streets (grey). The main trails cross the major streets at ’diffusers’ which provide a safer crossing while maintaining traffic flow.

Almost all residents can get home with one turn or less (terrific ’flow’).

Unlike a round-about that disrupts all traffic, a diffuser maintains flow on the higher volume street reducing time and energy, but the real advantage over the roundabout is much safer pedestrian crossing.

Most suburban cities require a percentage of the site as open space. This may be in dedicated city park or spaces exclusive to the use of the residents within the development. Each city will be different in their open space requirements. The park areas (dark green) in this particular neighborhood follow the contours of the land. The north part (upper part of the map) is on top of a hill allowing sledding (this is North Dakota!) or kite flying, and the remaining parkland follows a cascading ponding system along lower elevations. Both the trail system and drainage lead to a retail center at the southwest corner of the land (lower left). This method of design embraces the terrain and reduces storm sewer costs by embracing natural drainage flow.

To solve the problems of exclusion caused by the typical suburban transitional zoning we simply reverse the transition.

Figure 14 Reversing zoning transition makes housing inclusionary—not exclusionary. White is Single Family, Orange is Duplex.

Instead of having the highest density at neighborhood entrances, we place the lowest density and best housing at the front door. Disney’s Celebration, a New Urban design, does the same thing. As

price points lower, those residents drive through higher priced housing creating a sense of arrival without cheapening the feel of the development or image of the city it’s located within. Single Family (white) large lots are along the main streets with smaller single family or duplex (orange) lots in pockets behind the single family. The main trails lead to a church (yellow), senior housing (pink), and retail (green). A school (not shown) is across the street from the church.

Wide meandering walks add that special touch of elegance along the street and provide added sense of scale to the undulating open space adjacent to homes.

Figure 15 Sundance Village: Creating a sense of arrival is very important

Example #4: Rivers Edge— Sugar, Utah

There is a good reason why, now, we can enter a new age of more sustainable growth. Just 40 years ago a single property intersection of a lot line with a curved street would require a half hour of tedious geometric calculations, encouraging the simpler designs of the past. Today, automated software can produce a 1,000 lot development in the

same time span! Both suburban and New Urban design does not consider the living experiences within a home as tied to surrounding open spaces (if any).

Figure 16 A San Antonio project by a National home builder—no attention to how the floor plan merges with open spaces..

Figure 17 Same project as the above picture—but in aerial view. Where was ’passion’ in this land plan design?

Instead of using software to produce a faster cookie-cutter plan, we can harness (and develop) technology to produce better neighborhoods. Technology makes it possible to discover better design models. New models provided the basis to create new forms of software and training. Both developers and cities have the opportunity to build better neighborhoods—if they are passionate about building better communities to invest the time and effort.

Figure 18 This neighborhood in Orno, Minnesota uses the ’BayHome’ design method merging interior and exterior spaces.

This next example demonstrates the evolution of planning which merges both site design and architecture, providing a significant market edge above competing home builders. This evolution allows neighborhoods to be designed to a much higher level of detail increasing efficiency, function, value, and livability.

In 1999 Professional Builder Magazine called the BayHome method of design ’New Urbanism with a View’. It was the first time (ever) in planning, that the floor plan became a major component of the neighborhood design. This meant that communication and collaboration between all consultants (planning, architecture, engineering, and surveying) became critical at the initial design stages (also revolutionary).

Figure 19 BayHome: living space expands to adjacent open spaces and scenic views, merging planning and architecture

With just a handful of floor plan options, placing homes in a staggered relationship allows significant views both front (porch side) and side of every home. The staggering eliminates the ’alley’ look of a rear serviced home while providing space for two and three car garages.

BayHomes hide parked cars and garage doors, improving the look of the street and the neighborhoods. However, they are alternatives to attached housing such as townhomes and duplex units because the yards are common as well as the maintenance of them. To achieve this design they are platted as townhomes, not traditional single family lots along a public street.

This example, Rivers Edge is typical of how BayHomes are utilized on typical suburban neighborhoods. Like normal single family homes, there are very little economic barriers serving low and high income families.

Figure 20 Rivers Edge in Sugar, Utah uses BayHomes along the arterial street (lower right) and along the river (rear of the site).

The success of BayHomes with their attention to detail allowing expanded views influenced us to wonder: Why not have this attention to detail on every home?

Figure 21 The Fellowship Church redevelopment in Detroit shows low income ADA BayHomes to house disabled Veterans.

Example #5: Viera—Melbourne area, Florida

Viera in Melbourne, Florida takes land development design to a much higher level.

Figure 22 The original Viera architecture placed along the 35’ wide lots of the ’before’ plan would have appeared as above

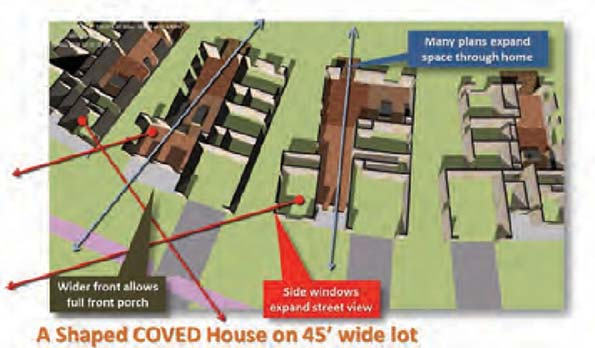

Not only does Viera harness all of the above methods of design, it also incorporates the coordination of architecture to lot shape, eliminating the largest problem in high density, narrow, single family lots (suburban and New Urban): reduced curb appeal and views. By coordinating both architectural design and creating a consistent angle between interior and exterior ’coved’ lots, the home can be widened at the front or rear:

Figure 23 A narrow home no longer has limited floor plan options nor the garage dominant streetscape using ’shaping’

What makes Viera unique and revolutionary, is that both developer and builder decided to throw out all the existing rectangular floor plans and make every home have the benefit of home-to-lot shaping! The resulting neighborhood when it is built by mid-2015 will certainly challenge competing homes being built at similar densities.

Figure 24 Viera Homes on the same 35’ wide minimum width as the before plan (similar density) as shown on Fig. 22!

Viera clearly demonstrates the advantages of advancements in home and land development design made possible when the consultants collaborate to take the extra effort and attention to detail needed to create sustainable suburban neighborhoods that will rival the New Urbanism, without waging war on suburbia per se.

Figure 25 Viera was the first development of many since that takes form and function to the next level.

From an economic and environmental perspective, Viera demonstrated a 38% reduction of infrastructure compared to the before plan (loosely based on New Urban design).

CONCLUSION

If land developers stopped contracting (paying) engineering consultants for mundane plat geometry to regulatory minimums and demanded better, change would be immediate. If universities taught design and collaboration instead of social engineering, we would have hope for a better future, both suburban and urban. If consultants imagined themselves living in the neighborhoods they design, we would have change. Complacency—not the idea of suburbia—is the primary cause of unsustainable growth. Suburban developers today must rediscover of the innovation that characterized the first wave of builders, who created, however imperfectly, an unprecedented wave of property ownership and privacy. Our challenge now is not to reject suburbia but to look for something that goes beyond replicating tradition, but actually improves how we live and interact with the natural world, and each other.

This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism called "America's Housing Crisis." The report contains several essays about the future of housing from various perspectives. Follow this link to download the full report (pdf).

Rick Harrison is President of Rick Harrison Site Design Studio and Neighborhood Innovations, LLC. He is author of Prefurbia: Reinventing The Suburbs From Disdainable To Sustainable and creator of Performance Planning System. His websites are rhsdplanning.com and performanceplanningsystem.com.