The Bureau of Transportation Statistics recently released preliminary data summarizing public transportation ridership in the United States for the calendar year 2015. The preliminary data from the National Transit Data program showed transit ridership in 2015 of 10.4 billion annual riders approximately 2.5% below the 2014 count and also smaller than the 2013 count. The American Public Transit Association using a slightly different methodology released data showing 10.6 billion annual riders versus 10.7 billion in calendar year 2014, a 1.26% year-over-year decline. Such differences between sources are common, resulting from differences in methodology and definitions, and unsurprising, given that data is preliminary and national data is dependent upon reporting from hundreds of different agencies.

It is important to recognize that it’s extraordinarily difficult to consistently grow transit ridership. We have had growing population, a rebounding economy, growing total employment, and an aggressively argued hypothesis that the millennial generation is meaningfully different than their forefathers—with urban centric aspirations and indifference toward auto ownership and use. Yet, transit ridership has remained stubbornly modest.

|

Indicator |

2015 versus 2014 |

Source |

|

U.S. Population |

+0.8% |

Census |

|

Total Employment |

+1.7% |

BLS |

|

Real GDP |

+2.4% |

BEA (third estimate) |

|

Gas Price |

-28% |

EIA |

|

VMT |

+3.5% |

FHWA |

|

Public Transit Ridership |

-1.3% to -2.5% |

APTA and NTD |

|

Amtrak Ridership (FY) |

-0.1% |

Amtrak |

|

Airline Passengers |

+5.0% |

The rebound in national vehicle miles traveled totals in 2015 (+3.5%) grabbed attention, as many had anticipated continued moderation. Couple that with modest declines in transit and Amtrak use and strong airline traffic growth, and one could argue the new normal for travel trends is looking more like the old normal.

When I entered full-time employment with a transit agency in 1980, industry leaders were touting the growth opportunities for public transit in light of the energy shortages in the late '70s. Throughout the intervening time, there have been myriad seemingly logical events that led to expectations of strong transit growth. Growing congestion, a growing appreciation of the role of transportation in influencing land-use, growing federal support, increasing gasoline prices, expansion of rail systems, sensitivity to the safety benefits of transit travel, potential economic benefits for passengers who reduce auto ownership and use costs, air quality concerns and, subsequently, climate impact concerns, and, more have collectively created almost perpetual expectations of a more promising future for public transportation. Indeed, transit ridership has grown some since its low point in the early '70s and subsequent dip in the mid-'90s, but the often-expected, sustained, or robust growth has never materialized.

More recently, demographic conditions, such as growing urbanization, declining driver's-license-holding and auto-ownership rates for young people, and evidence that the love affair with the automobile has waned, have renewed expectations. Sprinkle in technology enhancements that enable real-time information, robust trip planning, automated and more convenient fare collection, and integrated first-mile last-mile opportunities; add a dash of heightened concerns about climate change; and there remains a credible argument that transit has a bright future.

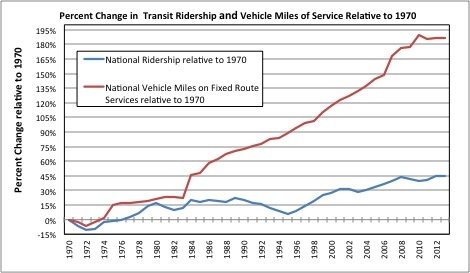

An often-cited constraint on the growth of public transit has been the assertion of resource constraints for providing the quality of service that would be attractive to more travelers who have other options. While transit supply remains well below the aspirational levels of many transit users and transit advocates, the data in the graph below indicates that supply has grown far more rapidly than demand for the past several decades. This is a report card on productivity that mom and dad would hardly be proud of. And a larger share of the ridership has moved to more capital intensive (and larger vehicle capacity) rail systems.

Source: 2015 APTA Public Transportation Fact Book, Appendix A, Historical Tables 2 and 8.

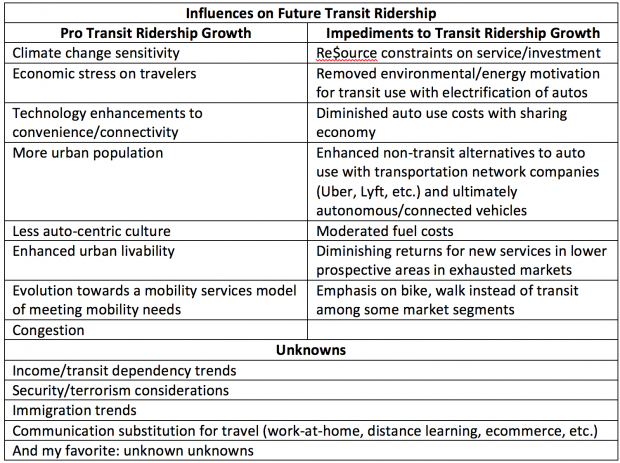

Gas prices have certainly been a factor in recent trends, but they can’t explain the fact that growing transit ridership seems as tough as getting bipartisan harmony in the nation's legislative bodies. Some cities are moving headlong into a more transit intensive future with aspirations of big ridership growth, like Seattle, where aggressive, multi-decade plans with big local funding commitment requests promise more transit supply. Other areas like Washington, D.C. are digesting the reality that more resources are required to sustain existing services, maintain infrastructure and meet underfunded pension obligations. The factors supporting or opposing ridership growth are numerous, with uncertainties dominating the lists.

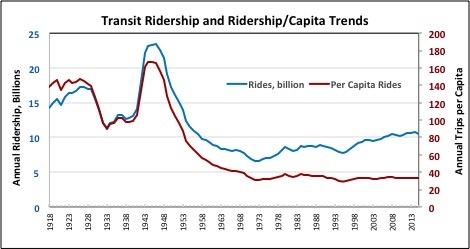

I generally like to have a theoretically robust basis for speculating on the future, but in light of the complexity of factors involved and the uncertainty in their trends, transit ridership forecasts are speculative. The per capita transit ridership trend in the graph below (red line) is a pretty straight horizontal line since about 1970 and just might be pointing to the future. History tells us to be careful in presuming we understand causal factors governing complex behaviors; if anything the degree of uncertainty is greater than ever.

Transit remains very important to each trip maker but how many trips are made in the future remains a guess, one that should be informed by a keen understanding of travel behavior and history and not just aspirations.

Source: APTA Public Transportation Fact Book, various years, Census.

This piece first appeared at Planetizen.

Dr. Polzin is the director of mobility policy research at the Center for Urban Transportation Research at the University of South Florida and is responsible for coordinating the Center's involvement in the University's educational program. Dr. Polzin carries out research in mobility analysis, public transportation, travel behavior, planning process development, and transportation decision-making. Dr. Polzin is on the editorial board of the Journal of Public Transportation and serves on several Transportation Research Board and APTA Committees. The opinions are those of the author—or maybe not—but are intended to provoke reflection and do not reflect the policy positions of any associated entities or clients.