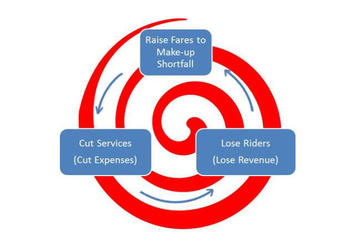

Denver’s Regional Transportation District (RTD) has entered what is known in the transit industry as the Transit Death Spiral. Ridership has fallen 7 percent since 2015. This reduces the funds available to operate RTD buses and trains, so RTD has cut service and increased fares to be some of the highest in the nation.

Reduced service and higher fares will depress ridership further. This will force RTD to cut service and perhaps raise fares again. And so it goes.

Much of RTD’s problem stems from its mania for an obsolete form of transportation: trains. Trains are great for moving freight, but for urban transit they were surpassed by buses more than 90 years ago. Since the introduction of what was called the Twin Coach bus in 1927, buses could move more people per hour, faster, at a far lower cost than rails.

Despite this, in 2004 RTD persuaded voters in eight metro Denver counties that increasing taxes to build new light-rail and commuter-rail lines would relieve congestion. RTD also promised that some of the new taxes would go to significantly improve bus service.

Instead, as critics (myself included) predicted, the proposed rail lines suffered huge cost overruns. In 2004, RTD estimated that building the airport and Gold lines would cost about $1.0 billion, yet it has spent $3.1 billion on these lines through 2017. Since 2004, it has also spent $3.0 billion on light-rail lines that were supposed to cost less than half that.

As a result, RTD had no funds left over to improve bus service. Instead, service has declined by 6 percent since 2004, which helps explain the decline in ridership.

What has all this spending on rail transit accomplished? The Census Bureau says that 4.8 percent of Denver-area commuters took transit to work in 2000. By 2017, after the construction of about 75 miles of new rail lines, this was down to 4.6 percent. It doesn’t appear that trains have relieved much congestion.

Other than cost, RTD’s problem is that transit, even rail transit, is slow. A 2017 report from the University of Minnesota Center for Transportation Studies finds that the average Denver-area resident can reach almost twice as many jobs in a 20-minute auto drive as in a 60-minute transit ride.

Low-income people understand that cars can get them to work quicker than transit, especially since RTD has cut their bus service. According to the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (table B08141), the share of Denver-area workers who live in households without cars declined from 3.3 percent in 2007 to 2.8 percent in 2017. Much of the decline was among low-income workers.

As a result, low-income workers are abandoning transit. The American Community Survey also shows (table B08119) that Denver-area workers who earn less $15,000 a year were 30 percent less likely to ride transit to work in 2017 as they were in 2007, while workers who earn more than $75,000 a year were 18 percent more likely to ride transit to work than in 2007. Rather than a service for those who can’t afford to drive, RTD has become a huge subsidy for those who don’t actually need it.

Ride hailing is also taking its toll. Moreover, it is likely that driverless ride hailing services will begin operating in Denver within two to five years, which will further impact RTD’s ridership.

Nor is RTD an environmentally friendly form of travel. RTD buses and light-rail lines use more energy and emit more greenhouse gases (from the power plants that generate the electricity for light rail) per passenger mile than the average SUV, and much more than the average car.

Contributing to the transit death spiral, RTD currently has about $3.5 billion of debt on its books. In addition, Denver Transit Partners – the company that built and operates RTD’s commuter-rail lines – has its own debt of around $400 million that RTD is contractually obligated to pay even if it isn’t on RTD’s books.

When RTD planned its rail system, it assumed sales tax revenues would increase every year without fail. When a recession causes sales taxes to decline, or even to increase more slowly than assumed, it has to dip into other funds to meet its debt obligations, and that means cutting service even more.

Another problem is that rail lines wear out after 30 years and must be replaced, practically from the ground up. RTD’s oldest light-rail line is 25 years old, which means it has about five years before it needs to be replaced. The logical thing will be to tear out the tracks and replace the trains with buses, but RTD has rarely been logical.

Unless RTD’s board takes drastic steps to reduce costs, it seems likely that the transit death spiral will continue. Voters should be extremely wary of any RTD proposals to increase taxes to solve this problem, as transit is becoming less relevant to Denver’s mobility and economy with each new year.

This piece originally appeared on Independence Institute.

Randal O’Toole is the director of the Independence Institute’s Transportation Policy Center and author of the recent book, Romance of the Rails: Why the Passenger Trains We Love Are Not the Transportation We Need.