The principal reason that large cities have developed is that they provide large labor (and housing) markets. A labor market is also a housing market, since virtually all who work in the metropolitan area also live there. The metropolitan area is the one location where there is one-to-one balance between jobs and resident workers (see: Alain Bertaud, Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities). Labor markets are independent of jurisdictional boundaries (municipality, county, or state), except where international boundaries restrict freedom of labor movement.

Obviously, large labor markets require transportation that permits residents to reach the maximum of jobs in a reasonable period of time (such as 30 minutes, which has historical significance, indicated below). Researchers such as Remy Prud’homme, Chang-Won Lee, David Hartgen, Gregory Fields and Steve Polzin have shown that a metropolitan area is likely to have better economic performance and job creation if a larger number of jobs can be reached by the average worker in a specified period. With the relatively recent development of transportation access measures, the 30-minute one – way work trip (commute) has emerged as an important planning standard (referred to herein as “30-minute commutes”).

Marchetti’s Constant

The 30-minute one-way work trip travel time has been called the Marchetti Constant, described by Italian physicist Cesare Marchetti. Jonathan English, writing in City Lab, provides a compelling history from 800 BCE to today. The concept has also been dealt with in newgeography.com articles here and here.

This article examines 30-minute one – way actual commutes shares by the two leading modes of travel to work, autos and transit, in the 53 major US metropolitan areas (over 1 million population). This excludes working at home, which has recently passed transit as the second largest employment access mode).

Rational Choices

One of the enduring myths embraced by many in the media and planning agencies is that people can readily switch from driving to transit without great inconvenience and much elongated travel time. In fact, for most people in major metropolitan areas, transit is not a reasonable choice. It may be too remote from their residence, too remote from their employment or just take too long. For these, choosing transit requires either not working or working in a less remunerative job, both of which mean a lower standard of living.

In fact, however, relatively few people have a reasonable choice between autos and transit. The work trip access data developed by the University of Minnesota Accessibility Laboratory indicates that the average worker can reach 56 times as many jobs in 30 minutes by car as by transit in 49 metropolitan areas over 1,000,000 population. Just to make it clear, this is 5,600% as many jobs, not 56% more jobs.

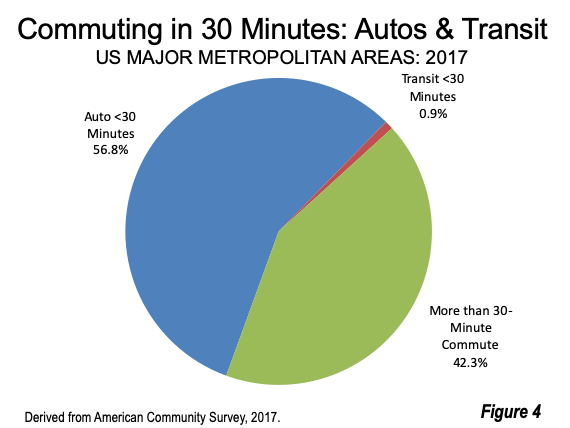

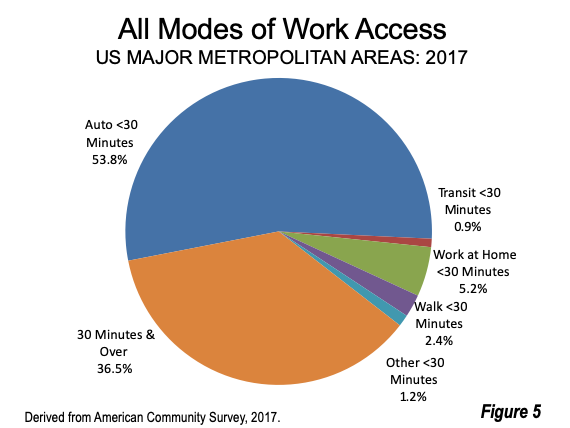

The reality, according to the 2017 American Community Survey is that 56.8% of major metropolitan area commuters reach their jobs in 30 minutes by auto, compared to only 0.9% by transit.These are “revealed preference” data, because they reflect the modes of transport used by people based upon the choices that they face (such as economic, access, and other considerations).

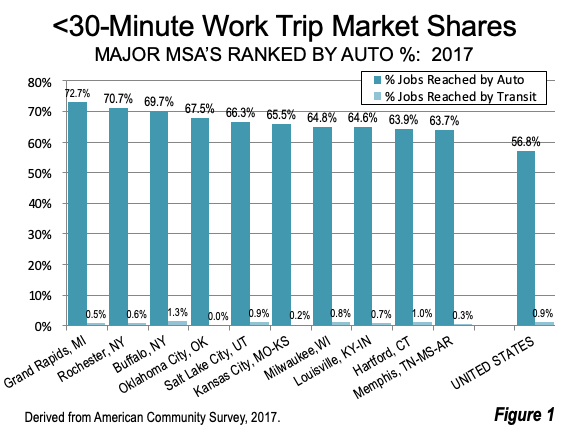

Grand Rapids: Where Auto Commuting is Best: The top 10 major metropolitan areas with auto commutes of 30-minute auto or less are illustrated in Figure 1. Grand Rapids tops the list, where and nearly 73 percent of the metropolitan areas commuters reach their jobs by car within 30-minutes. Grand Rapids is one of the smaller major metropolitan areas and is characterized by relatively low urban population density. Rochester, Buffalo, Oklahoma City and Salt Lake City round out the five top major metropolitan areas where workers are reaching their jobs within 30-minutes. With the exception of Salt Lake City, these all have lower than average urban population densities.

Among the major metropolitan areas where 30-minute automobile commuting is the greatest, commuting by transit is minuscule. For example, in Grand Rapids only 0.5 percent of commuters reach their jobs within 30 minutes by transit. Oklahoma City has by far the lowest 30-minute transit share, which rounds to 0.0 percent.

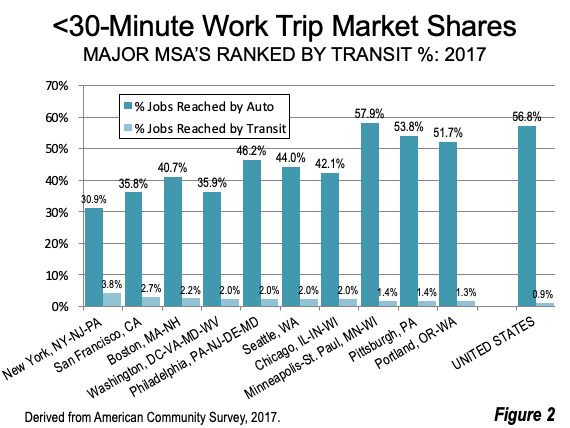

New York: Where Transit Commuting is Best: The top 10 major metropolitan areas in 30-minute transit commuting is, as is to be expected, New York. In the New York metropolitan area, 3.8 percent of traveling commuters reach their jobs by transit in less than 30 minutes. The San Francisco is second, at 2.7 percent, more than one quarter lower than New York. In five other areas, transit commuters are reaching 2.0 percent or more of the metropolitan jobs in less than 30 minutes . (Figure 2). These include Boston, Washington, Philadelphia, Seattle and Chicago. Each of these top seven major metropolitan areas includes a transit legacy city (municipality), except for Seattle.

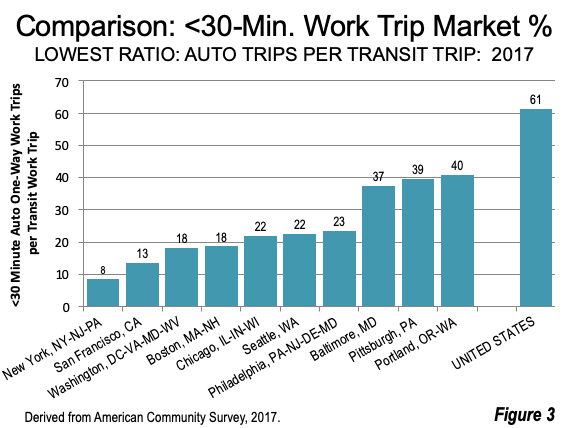

30 - Minute Commuting by Auto Compared to Transit: Overall, 61 times as many commuters reach their jobs by auto as by transit in the nation’s major metropolitan areas. As is evident from above, there are many more less than 30-minute commutes reachable by auto than transit in every major metropolitan area. In New York, commuters are reach 8 times as many jobs in 30 minutes as by transit. The same seven metropolitan areas that have the highest percentage of 30-minute commuters by transit also have the best transit performance relative to autos (Figure 3). Auto commuters do the best, by comparison, in Philadelphia, as 23 times as many reaching their jobs in 30 minutes as by transit. This is nothing to celebrate. Put in different terms, there are 800 percent as many 30-minute auto commuters in New York as transit, and 2,300 percent as many in Philadelphia.

30 - Minute Commute Advantage by Population Category

Overall, 57.7% of commuters who travel to work are able to reach their jobs in 30 minutes in the major metropolitan areas by auto or transit. The other 42.3% require longer to get to their jobs (Figure 4). If working at home and the other modes are included, 63.5% of US commuters access work in less than 30 minutes. Approximately six times as many access their jobs by working at home, than by transit. Further, there are even more 30-minute commutes by walking and other means (Figure 5).

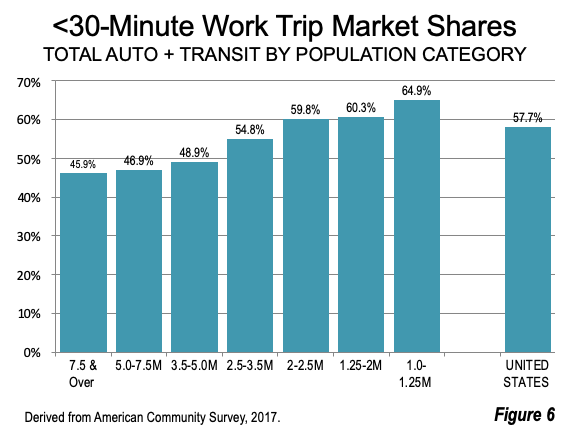

The percentage of less than 30 minute commutes is generally higher among the smaller metropolitan areas, ranging from 45.9% in the largest to 64.9% in the smallest (Figure 6). A number of factors are likely to contribute slower travel times in the larger metropolitan areas, such as greater congestion in the generally larger urban cores, the generally higher urban population densities and the slower travel times of transit, with the notable exception of Atlanta (Figure 8, below). The Atlanta exception was dealt with in reports by Alan Pisarksi and me and in a previous report.

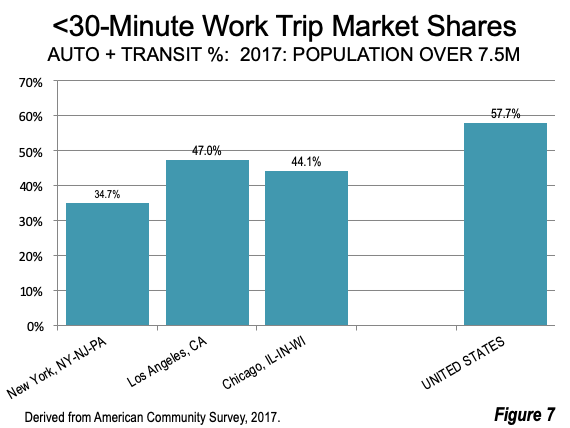

In the 7.5 million and over category, the 30-minute commute share is highest in Los Angeles and lowest in New York (Figure 7).

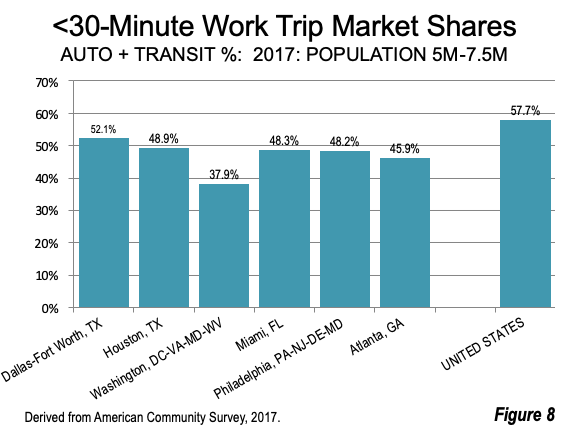

Among those in the 5.0 to 7.5 million category, Dallas-Fort Worth has the highest 30-minute commute share, and Washington the lowest (Figure 8). Dallas-Fort Worth has been rated as having the least congestion among any world urban area over 5 million for which there is data.

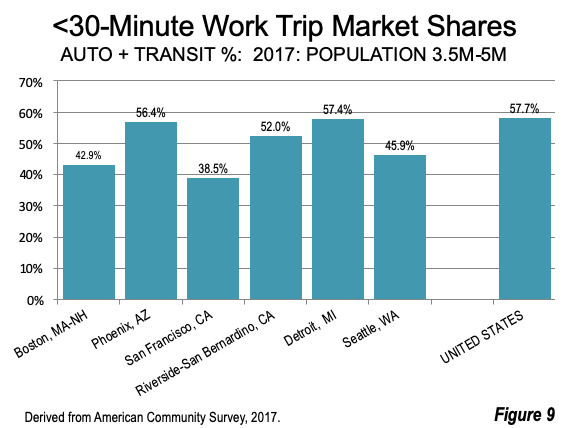

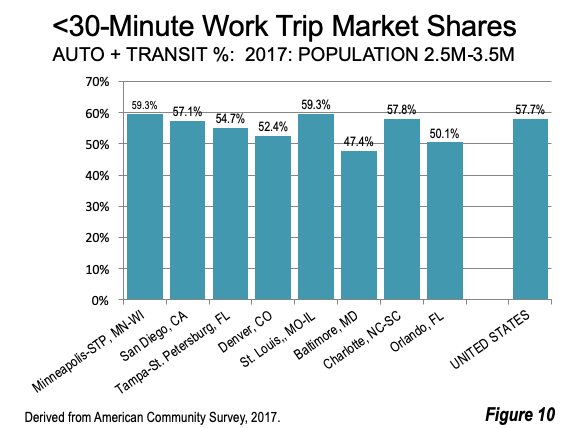

In the 3.5 to 5.0 million category (Figure 9), Detroit has the highest share of 30-minute commuters and San Francisco the lowest (Figure 10).

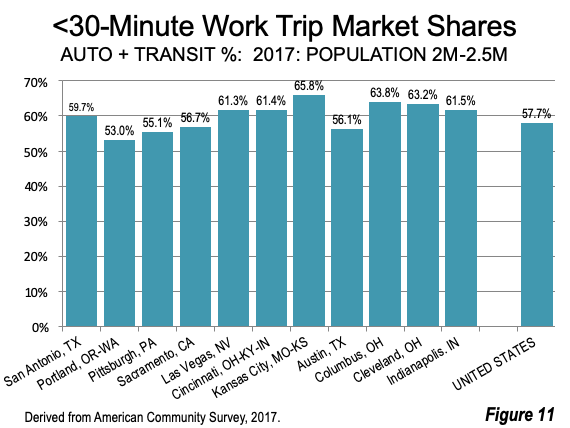

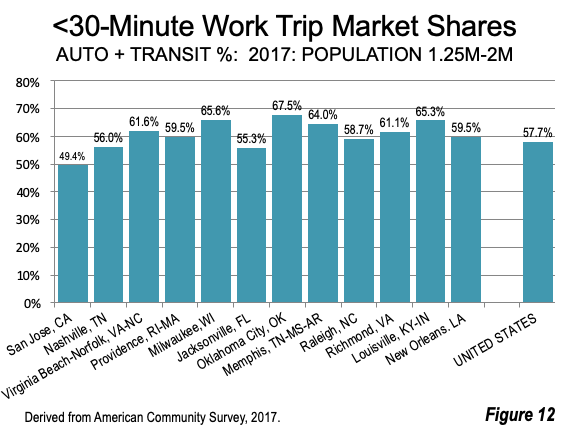

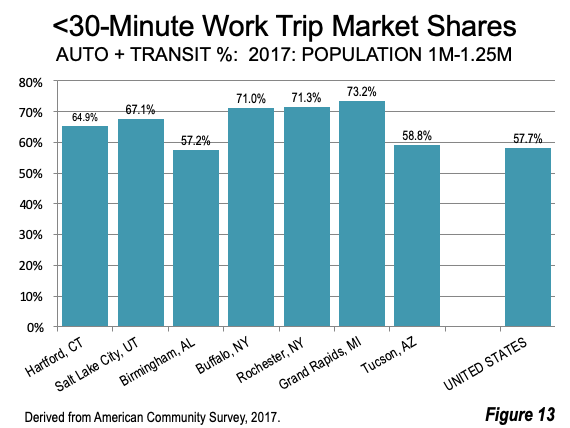

Among those with from 2 to 2.5 million (Figure 11), the highest is Kansas City and the lowest Portland (OR-WA). Oklahoma City has the highest 30-minute commute share in the 1.25 to 2.0 million category, while San Jose has the lowest (Figure 12). In the smallest population category (1.0 to 1.25 million), Grand Rapids is the highest, while Birmingham is the lowest (Figure 13).

Of Comprehensive Mobility and Niche Mobility

The huge imbalance between auto and transit commuting, even in New York with by far the best transit system in the nation indicates a huge difference , for most people, between autos and transit. Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers Professor Jean-Claude Ziv on what would be required to provide the geographical coverage of autos by transit in 16 world megacities, including New York and Los Angeles (see: Megacities and Affluence); it would require minimum annual expenditures about equal to the total public spending by all levels of government in the United States. We did not estimate the cost of providing equal access in terms of time, which would have made the cost even greater.

In a world where economic growth, affluence and poverty reduction depends on efficient labor markets, truly transit competitive with autos is virtually impossible (whether New York, Cairo or Shanghai). At the same time, transit plays a very important niche role in providing a majority of employment mobility to the largest downtown areas (central business districts), such as Manhattan, Brooklyn, Chicago, San Francisco and Jersey City’s Exchange place (also an “edge city”), as well as many similar districts outside the United States (such as Hong Kong, Shanghai, Toronto, Paris, and London. In essence, “transit is about downtown.” It’s time that urban plans are based on this reality.

Photograph: Downtown Brooklyn (bottom of pictured), Manhattan (across the East River) and Exchange Place, Jersey City (across the Hudson River), three of the six US employment centers with more than 50% transit market shares (by author). (by author)

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed by Mayor Tom Bradley to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. Speaker of the House of Representatives appointed him to the Amtrak Reform Council. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.