Washington’s Metrorail has sometimes been called “America’s Subway.” The first segment opened in 1976 (see photo above) and now extends over about 115 miles (185 kilometers), with 91 stations in the District of Columbia as well as suburban areas in the states of Virginia and Maryland. Metrorail has generally boasted the second strongest ridership of any urban rail system in the nation, following the New York City subway, which carried more than 11 times as many riders in the last pre-pandemic year, 2019.

Like other necessarily downtown oriented urban rail systems around the nation, the pandemic has decimated ridership. But Metrorail has been plagued by a separate set of particular difficulties, most importantly safety issues, over the last decade or so, as ridership had dropped significantly, even before the pandemic.

Pre-Pandemic Metrorail Ridership Losses

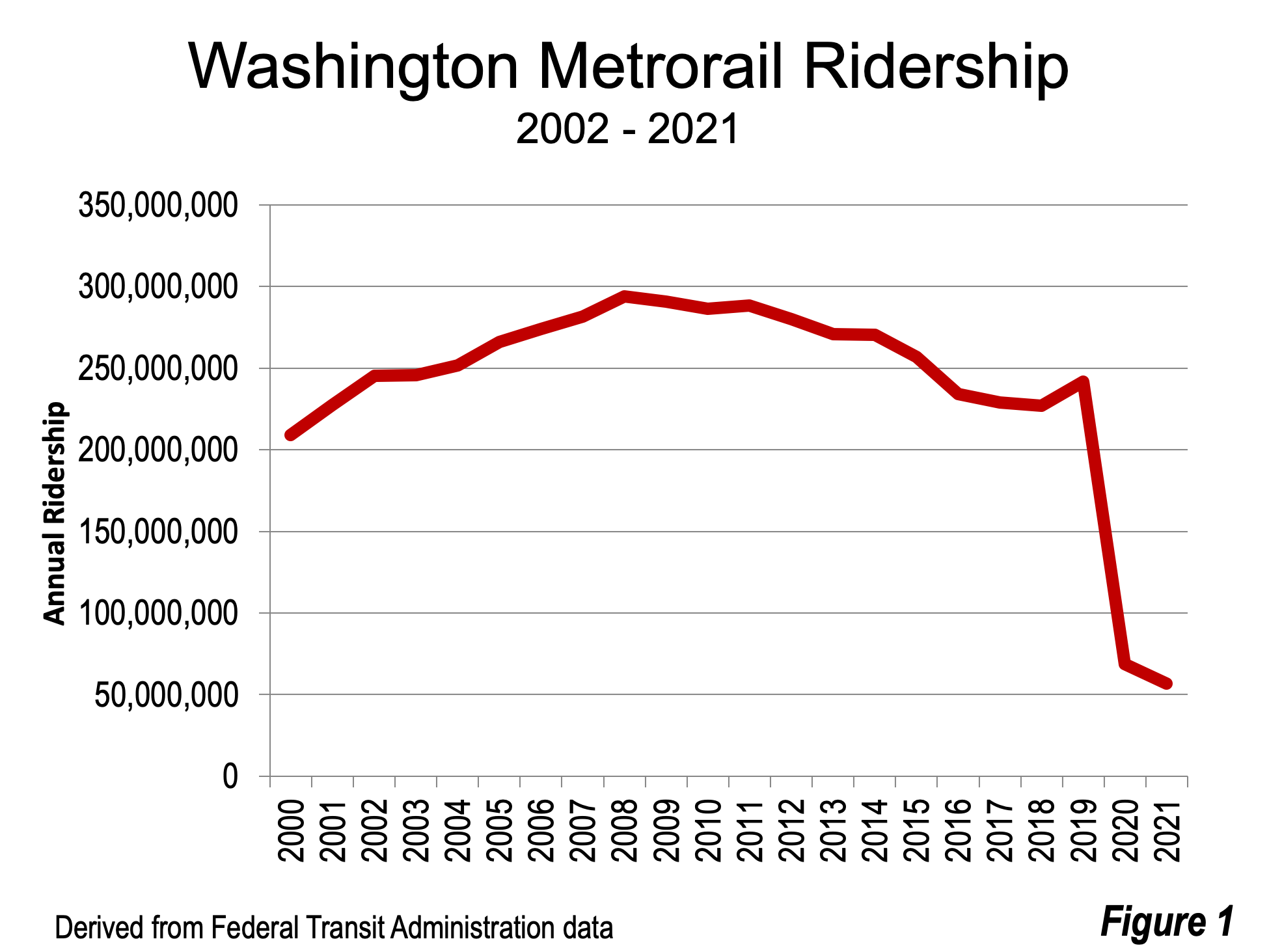

After peaking at 294 million annual rides in 2008, it took a decade for Metrorail to lose nearly one-quarter of its ridership just a decade later (227 million). Briefly, Metrorail fell to third place among US urban rail systems. The Chicago Transit Authority’s El (Elevated) gained 30 million annual riders by 2017, compared to Metrorail’s 65 million loss. Over this period Metrorail lost more riders than the total passenger traffic on urban rail systems in Seattle, Denver and Charlotte combined before the pandemic. By 2019, there had been a modest turnaround Metrorail, with ridership up six percent, and Metrorail back in second place (see: Note on Ridership Statistics).

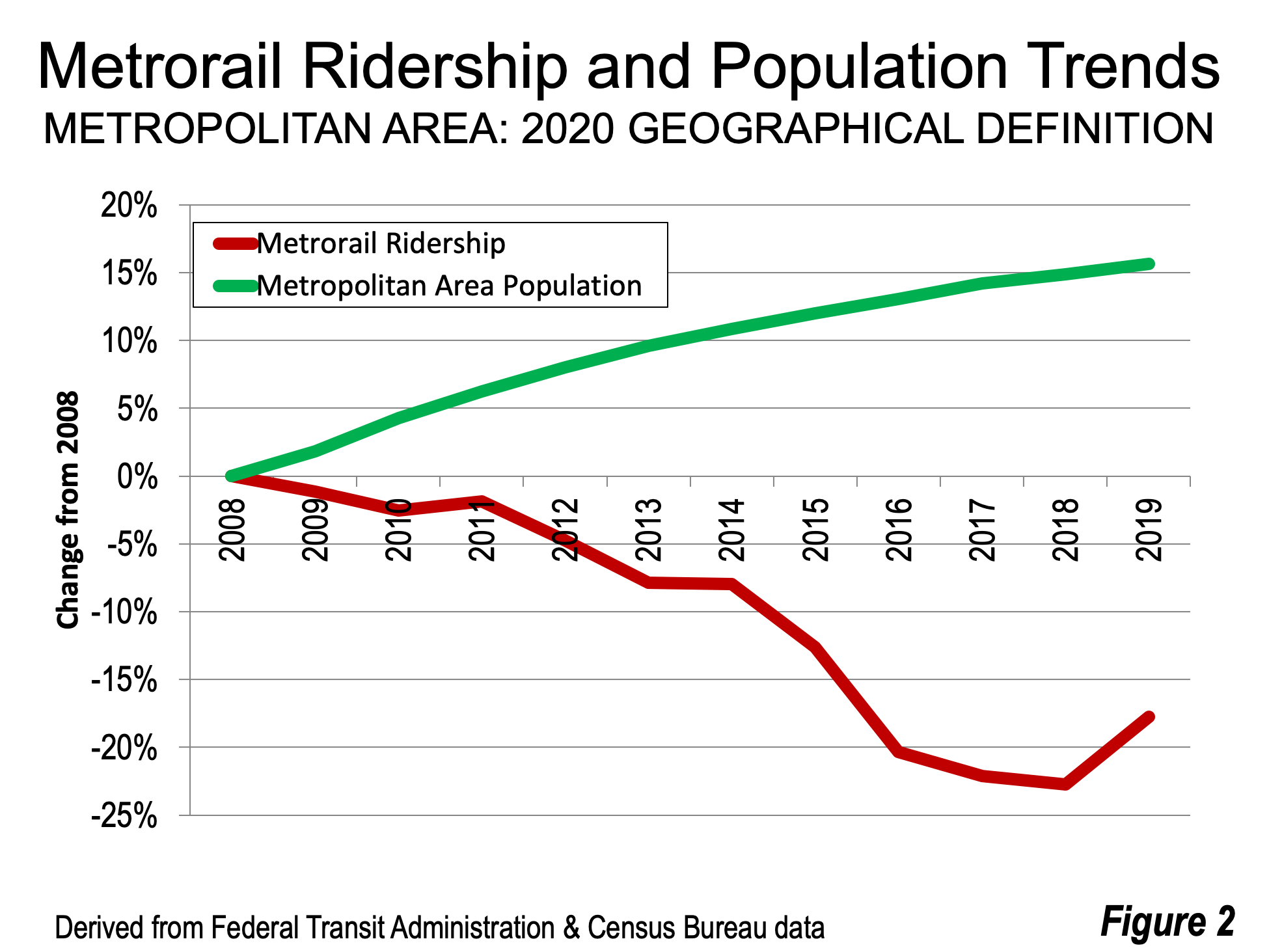

Figure 1 portrays ridership from 2000 to 2021, which shows the huge losses during the pandemic, but also the reduction in ridership from 2008. From 2008 to 2019, the Washington metropolitan area (the labor market) added 15.7% to its population, while Metrorail ridership was dropping 17.8%. (Figure 2, below)

Safety Issues From 2009 to the Pandemic

A New York Times article in 2016 mentioned factors contributing to the downward ridership trend:

“A train crash in 2009 killed nine people, and commuters have dealt with water seepage, broken escalators and frequent fires, including one in 2015 that resulted in the death of a passenger. On Tuesday evening, the Cleveland Park stop in Northwest Washington was shut down after a flash flood poured inches of rain into the station and caused escalators to fail.”

The Times said that “… riders consistently report service delays, cancellations and exceptionally long wait times, a recent internal report found.”

Another article cited a National Transportation Safety Board report conclusion that the Washington Metropolitan Transit Authority (referred to as “Metro”) had “failed to adequately learn from a series of dangerous and sometimes fatal episodes in recent years, making ‘little or no progress’ toward instituting a culture of safety” (See: Washington Metro System Failed to Learn From Accidents, Report Finds). Then, a yearlong plan was developed to complete three years of system maintenance in a single year, after “decades worth of infrastructure deterioration.”This program “paralyzed entire subway lines and the areas they serve.”

More Recent Safety Issues (2021-)

In early 2020, the pandemic decimated ridership at Metrorail and transit systems around the country. Metrorail ridership dropped 95% in April 2020, compared to the same month in 2019. As the nation began its recovery, transit ridership inched up, with Metrorail rising to approximately 70% below 2019 levels by September 2021.

Then, on top of the pandemic, new difficulties struck Metrorail less than six months ago. A single train experienced three derailments on a single day, Tuesday, October 12, apparently re-railing itself before the third mishap. After the third derailment, 187 passengers were evacuated, with one taken to a hospital for precautionary examination.

The problem was so deemed so serious that the independent Washington Metrorail Safety Commission ordered 60% of the system’s railcars to be taken out of service by following Monday, — all 748 subway cars in its 7000-series fleet, which were manufactured by Kawasaki Rail Car, Inc.The Commission was established under the interstate compact between the District of Columbia and the states of Virginia and Maryland in 2017, in response to widespread calls for independent oversight of Metrorail issues.

NTSB Chair Jennifer Homendy told DCist.com, “We are fortunate that no fatalities or serious injuries occurred as a result of any of these derailments. But the potential for fatalities and serious injuries was significant. This could have resulted in a catastrophic event.”

There was a preliminary finding that Metrorail knew about the flaw leading to the derailments as early as 2017, which prompted Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton (who represents the District in the House of Representatives) to say that it was shocking that Metro knew about the problems but nothing was said to the General Manager, the board of directors, or the Washington Metrorail Safety Commission.

Not surprisingly, there has been considerable Congressional consternation at these developments. In his opening statement at the House of Representatives Subcommittee Chair Gerald Connolly (D-VA) said that Metro is plagued by “a culture of mediocrity. … Failure of WMATA is not an option, and we can no longer afford a pervasive culture of mediocrity.” A number of riders shared their frustrations with Metrorail service at a recent District of Columbia Council Meeting, with one commenting to Metro officials that: “This isn’t good service, and you need to own that or there is no urgency to fix.”

One result of the service level reduction is that ridership has dropped nearly a quarter from its October 2021 level (210,000), when the Kawasaki railcars were taken out of service. According to Metro the withdrawn railcars are “out through until at least April.” Metro anticipates that it will take two to three years to restore ridership to pre-pandemic levels.

The Future?

However, the world has changed rather significantly since before the pandemic, and Metrorail’s principal market, downtown Washington, like central business districts in New York, Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, San Francisco and Seattle faces potentially far lower levels of employment, as remote work has increased during the pandemic. These seven municipalities (as opposed to metropolitan areas) accounted for about 60% of transit commuting destinations before the pandemic.

Many organizations are adopting hybrid work models, which allow employees to work three days or fewer at the employers site, and at home the rest of the time. Even if the total number of downtown employees recovers, there will be considerably fewer transit riders if they travel to work three rather than five days a week.

For example, The San Francisco Chronicle recently noted that “Despite indoor mask rules being lifted this month, office workers are not rushing back to their high rises downtown, and that has huge implications for businesses small and large.” Remote work expert and Stanford University professor Nicholas Bloom notes that hybrid work could reduce employment trips to downtown by up to 40%, though he expects it will be more like 30%. Even so, he notes, this is double what city officials expect. In a Board Workshop on February 10, 2022, Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BART) staff used a 70% of pre-Covid ridership as the baseline for its 10 year ridership projections (a 30% decline from pre-Covid levels). BART is the regional metro (subway) in the San Francisco metropolitan area.

The future is likely to be difficult for downtown oriented rail systems across the country, as the hybrid model is increasingly embraced. Even when all of WMATA’s safety issues are resolved, Metrorail may never again see the ridership levels of 2019, much less 2008.

Note on Ridership Statistics: Ridership data is from the Federal Transit Administration, using monthly reports prepared by Randal O’Toole (The Antiplanner), which expedites trend analysis (See: December2021Ridership.xlsx). (back to reference)

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy firm located in the St. Louis metropolitan area. He is a founding senior fellow at the Urban Reform Institute, Houston, a Senior Fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy in Winnipeg and a member of the Advisory Board of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University in Orange, California. He has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris. His principal interests are economics, poverty alleviation, demographics, urban policy and transport. He is co-author of the annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey and author of Demographia World Urban Areas.

Mayor Tom Bradley appointed him to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (1977-1985) and Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich appointed him to the Amtrak Reform Council, to complete the unexpired term of New Jersey Governor Christine Todd Whitman (1999-2002). He is author of War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life and Toward More Prosperous Cities: A Framing Essay on Urban Areas, Transport, Planning and the Dimensions of Sustainability.

Photo: Gallery Place Station (opened 1976) Washington Metrorail, by Dikaiosp, via Wikimedia under CC 4.0 License.

Accountability

Has anyone in Metro management or on its board been held to account for the "mediocrity"?