The US Bureau of the Census has just released an analysis of suburbanization showing that the nation continues to suburbanize, despite the consistent media “spin” that people are leaving the suburbs to move to core cities.

The report, Population Change in Central and Outlying Counties of Metropolitan Statistical Areas: 2000 to 2007, goes further than our previous 2000 to 2008 analysis that showed strong domestic outmigration from central counties to suburban counties and beyond.

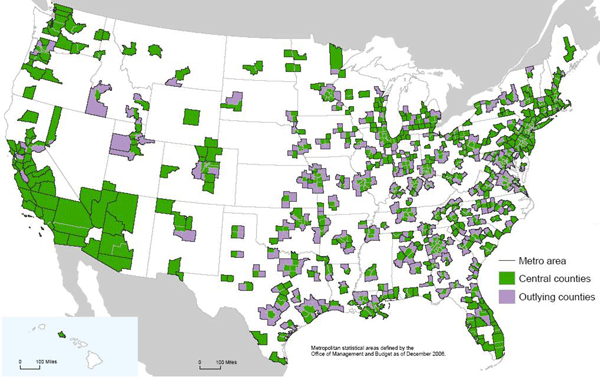

Our report compared trends between the core county (such as the 5 county New York City core) of each major metropolitan area. The new report compares population trends between what it terms “central counties” and outlying counties. The Bureau of the Census considers any county in the metropolitan area that is generally beyond the urban area (urban footprint) to be outlying. Thus, in Chicago, the report considers not only the core county of Cook, but also 9 additional counties as around it as central (Figure 1). Not surprisingly this means the bulk of the metropolitan area population is in the central counties (92%), however there is rapid movement even further out to the outlying counties.

This Bureau of the Census report tells us more about exurbanization than suburbanization. Exurbanization might be thought of growth that occurs outside the urban area, including its historic suburban periphery. It represents, if you will, “sprawl beyond sprawl”. You usually can tell when you are in an exurb because you have to drive through countryside to get to the “city” (For definition of urban terms, such as metropolitan area, urban area and city, see this document).

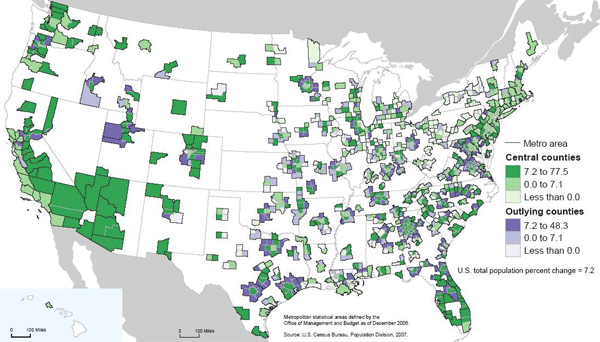

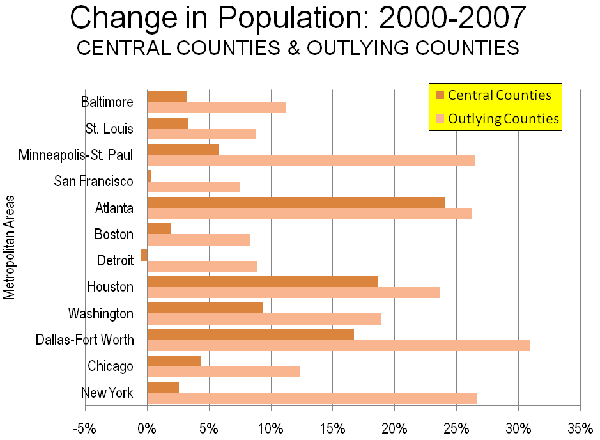

Between 2000 and 2007, these outlying counties grew 13.1 percent, nearly double that of the central counties, which includes the suburbs, at 7.8 percent (Figure 2). The report goes on to compare detailed results for the 12 metropolitan areas with more than 2,500,000 population that have outlying counties. In every case, the outlying counties grew faster than the central counties. On average, the outlying counties grew at 2.3 times the rate of the central counties (Figure 3).

- In San Francisco, the outlying county growth was 25 times that of the central counties.

- In New York, the outlying county growth was 10 times that of the central counties.

- In Boston and Minneapolis-St. Paul, the outlying country growth was between four and five times the growth in the central counties.

- In Baltimore, the outlying county growth was 3.5 times the growth in the central counties.

- In St. Louis, Washington (DC) and Chicago, the country growth was between two and three times the growth in the central counties.

The strongest central county performance occurred not in the much ballyhooed “cool” dense urban areas of the Northeast or Pacific Coast but in the largest metropolitan areas of the south, Atlanta, Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth.

- In Dallas-Fort Worth the outlying county growth was 1.9 times the growth in the central counties.

- In Houston the outlying county growth was 1.3 times the growth in the central counties.

- In Atlanta, the outlying county growth was 1.1 times the growth in the central counties.

The worst central county performance occurred in Detroit, where there was a net population loss. The outlying counties grew nearly 9 percent.

It may seem surprising that the Bureau of the Census analyzed only 12 metropolitan areas. Regrettably, Census metropolitan area definitions makes a broader analysis virtually impossible. Many metropolitan areas do not have outlying counties. That does not mean they do not have outlying or exurban areas. Riverside-San Bernardino is a good example. At the eastern end of this metropolitan area, a recluse might live less than 40 miles from the Las Vegas strip, yet be separated by 175 miles of desert and mountains from the edge of the Riverside-San Bernardino metropolitan area. The problem is that most metropolitan areas are defined by counties, and some counties contain much more area than can reasonably be considered as part of the labor market.

This fixation with county boundaries is unnecessary. Decades ago Statistics Canada figured out how to define metropolitan areas below the county level. The Bureau of the Census approach tends to obscure the growth of outlying areas, particularly in the largest counties. This is illustrated by our analysis of the Riverside-San Bernardino area from 2000 to 2006, which showed outlying areas to be growing at 2.5 times the rate of the core urban area.

Nonetheless, the conclusion of the new report is clear. The nation’s most remote suburbs – its exurbs – are growing much faster than the central counties. Whether this trend will now reverse, of course, is up to debate. Perhaps demographic changes and higher energy costs will slow expansion on the outer fringes. More likely, the current recession may well lead to less exurban growth, but history suggests this may prove only a short-lived trend.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

None of this should be

None of this should be surprising. And does it really matter whether the suburban development is central or outlying? In either case, the development is of a form that has been shunned by the intellectual world of design and planning. We've heard for 30 years how bad suburbs are, in our college education, at conferences, and in periodicals. More urban living may be right for childless singles and couples, but the realities of child-rearing draw those same people to the suburbs for a bit of back yard and some space for hobbies - and some landscape.

While suburban developers have been pushing the suburban model denser and more land-efficient, the academic and intellectual world of design and planning have focused on urban living as the answer, yet the focus has generally not included families with children. We have been disrespecting the residents, developers, architects and landscape architects that create suburbs with the goal of stopping suburban development altogether. This approach has not worked for decades.

It is time for us to take seriously the needs and wants of family living. Design and planning for families should be our highest intellectual priority, but not just because we see it as having the biggest footprint on the land. Recall the excitement of "modern living" in the 50s and 60s when Sunset Magazine promoted outdoor living and the integration of architecture and landscape architecture - for families of post-war United States. I think we can create that excitement again, but this time with an eye toward land use and the environment, but we won't be successful until the academic and intellectual world takes on the task as a positive endeavor.

-----------------

credit score

Exurban Growth Greater

I wonder whether this is a small numbers problem. The findings are presented as percentage increases and probably represent relatively small absolute numbers of residents. It would be good to express this article in terms of actual population change figures in addition to the percentages.

The Future of Suburbia

Americans have come to expect suburbia as an extension of their "American Dream", but that doesn't mean that new urbanist principles can't be incorporated to make suburbs and exburbs more walkable and sustainable. The problem with an exburb isn't it's distance from the city center, is the resident's distance for the office and other facets of their life. Current zoning reinforces this. We can defeat it though, with innovative development ordinances, encouraging light rail and other alternate transportations, and creative funding mechanisms to encourage the right kinds of development in our communities. We can have our 60x120 and walk to the coffee shop, it's not impossible.

Jonathan Brown

Whole Community Design