Kyoto is one of the most photographed cities in the world, and perhaps one of the most misunderstood. Most images of it feel decorative; tourist postcards masquerading as art, emptied of the quiet pulse that makes the city human. Taro Moberly’s Kyoto Dreaming breaks from that tradition. His work restores to the city its weight, its patience, its moral texture. His camera listens. Each frame insists that to see a place well is not an act of aesthetic consumption but of citizenship: an effort to attend, to notice, to dwell.

Moberly introduces his book not with self-assertion but with gratitude. Born to a Japanese mother and an American father, he grew up in California with Kyoto present in memory and story but distant in experience. He writes of visiting as a child - the grandeur and vastness of Kyoto Station, the floorboards of Nijo Castle, the toy-train shop on the top floor of Daimaru. In 2015 he moved there, returning to the place his mother was raised and his grandparents had called home. The move was not simply geographic; it was formative. “I discovered so much about the unique and fascinating culture of my adopted homeland,” he writes. “Kyoto has changed how I see the world and helped me become the person I am today.” When he returned to California in 2023, he carried the city inside him. “Within myself,” he concludes, “I still see Kyoto as a major part of my identity.” The book is less a record of that period than a testament to what the city taught him: that meaning and belonging are earned through attention.

The opening photographs tell the story. Two figures sit on the steps of a temple, dwarfed by the roof’s massive eaves. They are enveloped in silence. The composition honors scale without losing intimacy; we are made to feel the proportion between person and place. Moberly’s power lies in this restraint. His images are not declarations but invitations; to linger, to feel the density of the ordinary. In a time when nearly every image demands to be consumed instantly, his work asks us to slow down. His palette is subdued, his tones favoring twilight and rain. The light is not dramatic but devotional. Kyoto, in his hands, becomes less an object than a conversation: between architecture and weather, between time and memory, between the photographer and the city that made him.

To walk through the book is to sense the rhythm of a life lived attentively. We move from courtyards and alleys to the quiet ritual of commuting; umbrellas passing under red lights, taxis idling on wet streets, a parent guiding a child along a stone path lined with cherry blossoms. The repetition of these scenes accumulates into a moral vision. Moberly does not aestheticize civility; he observes it. His Kyoto is not the idealized city of postcards but the functioning city of mutual awareness, where strangers share space without spectacle. In this sense, his art offers something civic. The sociologist Richard Sennett described cities in his The Conscience of the Eye: The Design and Social Life of Cities essentially as theaters of encounter, sustained by the way strangers learn to look at one another. Moberly’s photographs record that encounter in real time. Every image reveals the choreography of coexistence: the small courtesies that hold urban life together. Pedestrians pause, cars yield, umbrellas tilt just enough to avoid collision. It is a social order built on perception.

The book’s stillness is deliberate. In an age of acceleration, stillness itself becomes a statement. Moberly resists the compulsion to dramatize. His camera does not chase decisive moments; it waits for coherence to reveal itself. This patience is a moral stance. It rebukes the attention economy that governs both photography and public life. Where the digital image thrives on speed and self-display, Moberly’s work restores scale and humility. The figures he captures are not subjects to be possessed but neighbors to be regarded. The act of seeing becomes relational, not extractive. The city, through his lens, is an organism of shared restraint.

Light is his great ally. In Moberly’s Kyoto, illumination functions like character: by turns tender, elusive, and instructive. Dawn glows faintly on tiled roofs; dusk turns wet streets into mirrors; neon reflections shimmer across taxi windows. He refuses the oversaturated brightness of commercial travel photography. His colors breathe within limits, his blues deepening toward memory rather than spectacle. In that restraint lies reverence. He allows light to emerge as revelation; to arrive, as grace does, without force. The viewer can feel the hours spent waiting for the right balance between luminosity and shadow, as if patience itself were a kind of prayer.

The formal discipline of the images echoes the discipline of the city. Kyoto’s architecture has long embodied order without rigidity - geometry in the service of grace - and Moberly composes with the same ethos. Lines of roofs and alleyways guide the eye gently; depth is earned through perspective, not manipulation. One image of wooden facades glistening after rain captures the principle perfectly: symmetry balanced by warmth, precision softened by use. He understands that restraint is not absence but articulation, that beauty often arises when ambition gives way to attention. In his visual grammar, order is not a constraint but a form of respect.

What makes Kyoto Dreaming resonate, though, is its humanity. The photographs breathe with companionship: a couple in conversation, a worker in the rain, a child discovering spring. The scenes are neither anonymous nor sentimental. They affirm continuity in an age obsessed with rupture. The red jacket of a child beneath pale blossoms becomes a symbol of renewal, the small assertion of color in a world rendered gray by haste. Moberly’s empathy is architectural, he gives his subjects room to exist within the frame. The result is intimacy without intrusion. He treats each life as belonging to the larger composition of the city, an act of recognition that carries its own civic weight.

As the book unfolds, its emotional key deepens from observation to gratitude. The late-night cityscapes - headlights diffused in rain, reflections stretching across wet crosswalks - feel like meditations on endurance. Kyoto, far from a timeless relic, appears here as a living organism: mortal, changing, resilient. Moberly captures that fragility with affection rather than melancholy. His attention dignifies transience. He shows how the fleeting can still feel eternal when looked at with care. That sensibility, inherited from the city’s own traditions, becomes the moral spine of the book: to see clearly is to care; to care is to remain human.

Moberly’s return to California closes the narrative but not the connection. “The city, the culture, and the people of Kyoto have left a profound impact,” he writes. “I will be forever grateful for the lessons and character taught to me by what now feels like my second home.” Gratitude is a rare word in contemporary art, but it fits him. He has made gratitude into a method, an aesthetic and a moral discipline. His photographs do not demand recognition; they offer it. In a culture addicted to novelty, this is a radical act. He reminds us that reverence is not nostalgia. It is attention sustained across time.

What emerges from Kyoto Dreaming is a philosophy of looking that transcends place. Moberly demonstrates that belonging begins with perception - that the ethics of seeing and the ethics of citizenship are inseparable. Cities depend on this kind of vision: on people who notice, who yield, who understand that public life survives through small acts of regard. His photographs are, in that sense, civic instruction. They teach us how to inhabit our own streets: how to look again at the surfaces we hurry past, how to find coherence in the weather of daily life.

The book could easily have been another exercise in aestheticized travel, but Moberly refuses that path. His work carries no slogans, no filters of irony or self-display. It asks us instead to practice the ancient discipline of looking until we actually see. In doing so, he joins a lineage that stretches from Saul Leiter’s New York to Masahisa Fukase’s Japan: photographers who understood that light, patience, and moral attention are ways of honoring the world.

In the end, Kyoto Dreaming is less a photobook than a form of civic meditation. It restores the bond between perception and gratitude. It reminds us that beauty is not found in the exceptional but in the continuous; in streets walked daily, rituals repeated, faces glimpsed in passing. The health of any culture depends on its ability to see in this way. When we lose that capacity, we lose not only art but sympathy, not only beauty but belonging.

Taro Moberly’s achievement is to make seeing itself feel like an act of care. Through his lens, Kyoto becomes more than a city; it becomes a teacher. It reveals how civilization survives: not through grand gestures or perfect design, but through the quiet labor of attention - one person, one street, one beam of light at a time.

Samuel J. Abrams is a professor of politics at Sarah Lawrence College, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and a scholar with the Sutherland Institute.

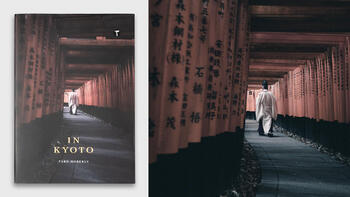

Photo: Kyoto Dreaming book cover, via Taro Moberly's Instagram.