My recent post on counting the long term costs of building rail transit got a lot of hits – and as expected a lot of pushback.

There are a lot of people out there that are simply committed to the idea of rail transit, no matter how unwarranted a particular line or system might be.

I find it interesting that the place with the most people applying serious skepticism to transit projects seems to be New York – the place with the biggest slam dunk of a case for it of any city.

Lots of people, for example, have critiqued the proposed Brooklyn-Queens light rail line. In a city where there’s a desperate need for more transit, advocates are very focused on making sure the limited capital we have gets spent on useful projects. Not everyone agrees with each other, but there’s a robust debate, focused on the actual merits.

In cities without much experience of transit, there appears to be a huge bias in favor of very expensive rail projects regardless of their merits.

Some have asked me whether I support Bus Rapid Transit. I can, in some circumstances. Though Alon Levy has convinced me that the economics of South American style BRT don’t necessarily transfer to high income countries.

What I do very much support is significantly improved Plain Old Bus Service (POBS).

Most cities in America have pretty awful bus service, with meandering, radial routes that run infrequently and are basically deployed as a social service.

Contrast that with Chicago or LA (or even New York, despite its subway dominance), where we see bus grid networks that run with reasonable frequency.

I define “reasonable frequency” as meaning I can show up at the stop without consulting a schedule or tracker app, confident that my max burn on wait time is at least semi-humane. Ten minute or less headways would be best, but I can live with 15.

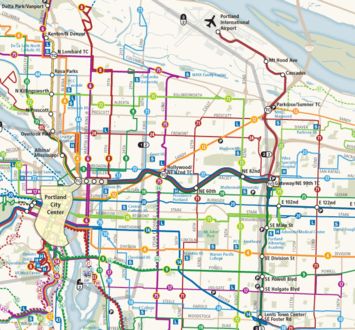

Jarrett Walker has highlighted the role of Portland’s high frequency bus grid, launched in 1982, as changing the game there and making the city’s subsequent light rail system actually functional.

Thirty years ago next week, on Labor Day Weekend 1982, the role of public transit in Portland was utterly transformed in ways that everyone today takes for granted. It was an epic struggle, one worth remembering and honoring.

I’m not talking about the MAX light rail (LRT) system, whose first line opened in 1986. I’m talking about the grid of frequent bus lines, without which MAX would have been inaccessible, and without which you would still be going into downtown Portland to travel between two points on the eastside.

Pretty much any city could benefit from a better POBS network and higher frequencies. This is where there is vast opportunity to invest in American transit without breaking the bank.

Yes, buses cost money. I’m not saying its free. This is where I say we should spend more. A solid POBS system is just the basics to be in the game for any city looking to retrofit transit culture.

Even Portland, the city held up as the exemplar for light rail investment, started by getting its bus system right.

Aaron M. Renn is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a contributing editor of City Journal, and an economic development columnist for Governing magazine. He focuses on ways to help America’s cities thrive in an ever more complex, competitive, globalized, and diverse twenty-first century. During Renn’s 15-year career in management and technology consulting, he was a partner at Accenture and held several technology strategy roles and directed multimillion-dollar global technology implementations. He has contributed to The Guardian, Forbes.com, and numerous other publications. Renn holds a B.S. from Indiana University, where he coauthored an early social-networking platform in 1991.

Portland Bus Grid. Image via Human Transit

The efficiency of rail transit.

The chief advantage of rail transit is that its effects are tightly and permanently tied to very specific geographic locations. This enables real-estate speculators to make a lot of money by buying up the right locations in advance. It is especially profitable to the big players, who may have knowledge, long in advance, of where the trains will run, and who may well be able to influence the planning of the routes. It also encourages future subsidies to developers and other players at the chosen locations, since the governments will be inclined to throw more money at them if needed to preserve their original investment.

Rail also involves major infrastructure projects. This brings the big contractors and the unions on board. Banks make easy money financing the big deals. Large businesses can get the government to pay for building facilities for private business at the chosen sites to help make those sites viable; the subsidized businesses run no risk, since they need not make any long-term commitment to that site. With big business, banks, and unions in the game, both political parties are on the side of rail.

Since so much money is involved in rail projects, there is profit also for consultants of all sorts--as long as they are of the obliging sort--to give a veneer of planning to the operation, and to provide the politicians involved with authoritative-looking statistics to feed to journalists, who can fill their wordage quotas from the handouts without having to stick their necks out by doing independent thinking.

The physical magnitude, cost, and duration of rail projects also give a huge ego boost to all involved, increasing their apparent importance and public prominence, and giving all sorts of opportunities for little acts of patronage.

In contrast to this, what do buses have to offer? The technology has no glamor or novelty value to appeal to grandstanding politicians or hack journalists. Bus riders are little people. They may give no money at all to politicians, and even if they do, "retail" collection of bribes is much less efficient than collecting large sums from a few big players.

The high frequency bus grid is the least effective solution of all, since it might eliminate public demand for more profitable projects.