NewGeography.com blogs

Over the last year, celebrities such as Yoko Ono, Sean Lennon, Robert Redford, Mark Ruffalo, Mario Batali, Scarlett Johansson, Alec Baldwin, and Matt Damon have spoken out against the expansion of natural gas drilling. “Fracking kills,” says Ono, who has a country home in New York. “It threatens the air we breathe,” says Redford.

In fact, “gas provides a very substantial health benefit in reducing air pollution,” according to Daniel Schrag, director of Harvard University’s Center for the Environment. There have been “tremendous health gains” from the coal-to-gas switch, MIT economist Michael Greenstone told The Associated Press. Indeed, air pollution in Pennsylvania has plummeted in recent years thanks to the coal-to-gas switch. "Honestly," added Greenstone, "the environmentalists need to hear it."

Fracktivism might be dismissed as so much celebrity self-involvement had it not reversed the national environmental movement's longstanding support of natural gas as a bridge to zero-carbon energy — and kept shale drilling out of New York state. Last week, Governor Andrew Cuomo was set to green-light 40 demonstration gas wells in a depressed part of New York until Natural Resources Defense Council attorney Bobby Kennedy Jr. called him and asked him not to.

Bill McKibben and his organization 350.org have made common cause with the anti-fracking movement, as has the Sierra Club. NRDC went from being supportive of a coal-to-gas switch to opposing the expansion of gas production. Even the Environmental Defense Fund’s chief, Fred Krupp, said in a debate last month that he opposes the expansion of natural gas.

All of this comes at a time when carbon emissions are declining in the US more than in any other country in the world. The USA is the global climate leader, while Europe and Germany are returning to coal. The main reason is gas, which increased last year by almost the exact same amount that coal declined.

Just a few years ago, environmental leaders were saying that we faced a climate emergency, that emissions must start declining rapidly, and that enemy number one was coal. Now the same leaders are saying we have to stop shale fracking even though it is crushing coal and driving down American carbon emissions.

Of course, the fractivism isn't really about the fracking. Matt Damon's anti-natural gas movie was originally an attack on wind farms. In 2005, Bobby Kennedy Jr. helped lead a campaign to stop the Cape Wind farm from being built because it will be visible from the Kennedy compound. Meanwhile, he was championing the construction of a massive solar farm in the Mojave Desert, 3,000 miles away — itself opposed by local environmentalists.

Fracktivists like Mark Ruffalo protest that his NIMBYism isn't pro-coal. He told AP that we don’t need natural gas; we can easily switch from coal directly to solar panels, like the ones Ruffalo installed on his Catskills house.

But when the sun isn’t shining on Ruffalo’s roof, he’s mostly getting his electricity from natural gas. In order to accommodate the intermittent nature of solar and wind, utilities rely on natural gas plants, which can be quickly ramped up and down to keep the lights on. Contra Gasland’s Josh Fox's claims about using "compressed air" in a recent debate with Ted at Salon.com — cheap, utility-scale energy storage simply doesn't exist.

Privately, scientists and analysts within national environmental organizations are appalled that celebrity fractivism could get in the way of the coal-to-gas shift. They say the fracktivists undermine green credibility, and are disturbed by the failure of their movement’s leadership.

But there’s little reason to expect national green leaders will become, well, leaders. They will likely continue to follow donors who demonstrate time and again that what matters most to them — whether in the case of a nuclear plant in Long Island, a wind farm in Cape Cod, or a gas well in the Catskills — is the view from their solar-plated eco-compounds, not the potentially catastrophic impact of global warming on the planet.

This post first appeared at TheBreakthrough.org.

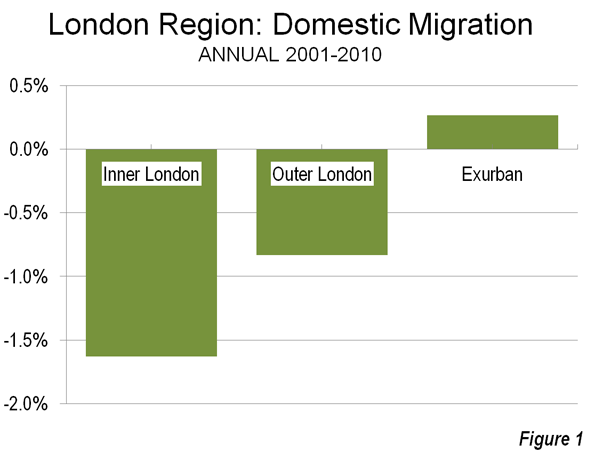

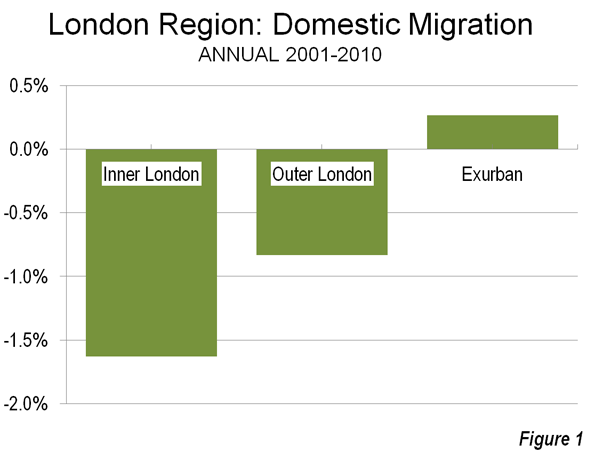

As reported in The Evolving Urban Form: London, last July the Greater London Authority (GLA), located inside the Green Belt, grew strongly from 2001 to 2011, though remains well below its peak estimated population in 1939. Substantial domestic migration from the core area to the exurbs was a major contributor to their growth during between 2000 and 2010 (Figure 1).

Obviously, with all that growth and all that domestic out-migration, international migration had to be driving the population growth in the GLA. The British Broadcasting Corportation (BBC) confirms that, reporting that, for the first time "white British" residents of GLA represent a minority of the population. At 45 percent, this population segment is down from 58 percent in 2011.

Whites, however, remain a majority, with more than 1.3 who do not consider themselves British, according to the 2011 census data. The combined white population is nearly 60 percent of the GLA total. The table below provides the ethnic data as reported by the Office for National Statistics.

| Greater London Authority: Ethnicity |

|

|

| 2011 Census |

|

|

|

|

|

| All categories: Ethnic group |

8,173,941 |

100.0% |

|

|

|

| White: English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British |

3,669,284 |

44.9% |

| White: Irish |

175,974 |

2.2% |

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller |

8,196 |

0.1% |

| White: Other White |

1,033,981 |

12.6% |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group: White and Black Caribbean |

119,425 |

1.5% |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group: White and Black African |

65,479 |

0.8% |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group: White and Asian |

101,500 |

1.2% |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group: Other Mixed |

118,875 |

1.5% |

| Asian/Asian British: Indian |

542,857 |

6.6% |

| Asian/Asian British: Pakistani |

223,797 |

2.7% |

| Asian/Asian British: Bangladeshi |

222,127 |

2.7% |

| Asian/Asian British: Chinese |

124,250 |

1.5% |

| Asian/Asian British: Other Asian |

398,515 |

4.9% |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British: African |

573,931 |

7.0% |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British: Caribbean |

344,597 |

4.2% |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British: Other Black |

170,112 |

2.1% |

| Other ethnic group: Arab |

106,020 |

1.3% |

| Other ethnic group: Any other ethnic group |

175,021 |

2.1% |

|

|

|

| Source: Office for National Statistics, United Kingdom |

|

|

Coal electricity declined by 12.5 percent in 2012, mostly driven by the switch to natural gas, which increased by almost the exact same amount (217 terrawatt-hours) as coal declined (216 TWh), according to new annual numbers released by the US Energy Information Administration.

Wind electricity increased as well — by about one-tenth (20.5 TWh) as much as gas. Solar increased a little more than one-hundredth as much as gas (2.5 TWh).

The figures come at a time when renewable energy advocates have claimed that wind and solar have been responsible for the big declines in coal — claims that do not stand up to scrutiny, according to a new Breakthrough Institute analysis.

Indeed, the new numbers highlight the key difference between gas and solar and wind. Where taxpayers subsidized unconventional gas exploration from 1980 to 2002 to the tune of $10 billion, natural gas in recent years has been replacing coal without subsidies.

Wind and solar, by contrast, remain almost wholly dependent on public support. Uncertainty last year over whether Congress would renew the key wind subsidy meant that less than half as much new wind will be installed in 2013 as was installed in 2012.

Where the problem for wind has been its high cost, the problem for gas is that it has become too cheap. Natural gas production slowed last year in the face of unprofitably low prices caused by overproduction.

This does not mean that subsidies for solar and wind should be cut, only that they should be reformed. Instead of subsidizing the production of electricity from the same old technologies, we need the kind of innovation that allowed natural gas to become cheaper than coal.

This piece first appeared at The Breakthrough.

A recent story over at Atlantic Cities got me thinking about a debate that’s heated up over the last few years: urban parking policy for churches.

Per Atlantic Cities, San Francisco has decided to start charging for metered parking on Sundays. This is starting to happen across America. In San Francisco, as in Chicago and elsewhere, the driver (no pun intended) appears to be revenue raising, plain and simple.

This has angered many attendees of local churches (who have in many cases now moved out of town and drive in for services). They seem to believe that they have a constitutional right to free parking on Sunday mornings. On the other side, of course, are bicycle advocates, who are positively gleeful. (Bicycle advocates are without a doubt the single most self-righteous advocacy group I know, which is why so many people who otherwise might support reasonable pro-bicycling policy can’t stand them).

I think a more nuanced approach should be taken, based on neighborhood conditions and creating the right incentive structures. For example, in some places across the country (San Francisco and Chicago come to mind again), it’s traditional for church goers to park even in what would otherwise be illegal spots. In general, this isn’t a problem – at least from my personal observations in Chicago. Traffic is pretty light on Sunday mornings, and it doesn’t cause any problems.

What’s more, enabling that temporary use of public space for a couple hours on a Sunday morning is exactly the sort of thing we need more of, not less. An institution like a church that has a single demand spike for parking during a generally low demand period is a great candidate for flexible uses of public space that would otherwise be underutilized. Liveable streets advocates are quick to decry the empty lanes off peak from oversized roads. So what’s the problem with putting a boulevard on a “road diet” on Sunday morning by using a lane for parking? Sounds like a winner to me. I’d be asking what other types of institutions or events could do similar things.

And consider, what will happen if churches are banned from using these spots or otherwise have to pay? Well, it depends on the neighborhood, but it’s easy to see what organizations often do when they need parking: build parking lots. Do we really want churches acquiring private off street lots that will sit empty 166 out of 168 hours per week – and generate no property taxes? It makes no sense to me. Why would we want to create incentives for people to own parking lots just because some folks hate cars? We should be going exactly the other direction. There are way too many church parking lots already if you ask me. We should be trying to cut deals with them to open that land up for development by making temporary blocks of street parking available for a couple hours on Sundays.

Now, in places where there is legitimately congestion and/or parking shortages on Sunday mornings (and San Francisco might be a case here – I don’t know for sure), implementing parking charges and restrictions would certainly be reasonable. The principal reason for allowing these church uses in the first place shouldn’t be some religious exemption per se, but rather enabling a local chronologically niche use to take advantage of underutilized public space. (Keep in mind that many other local users get truly special privileges based solely on their local presence: loading zones, valet zones, residential parking – and the latter is usually de facto free). If the space is over-subscribed, then feeding the meters to help rationalize demand is reasonable, and the churches should stop grumbling.

In short, we should be basing this on some type of rational decision process based on neighborhood conditions, setting the right overall incentives, and balancing the needs of competing uses, not pandering to churches treating illegal spots as if they were some ancient feudal right, nor sanctimonious bicyclists behaving as if a double parked car on Sunday morning is a menace to the planet or to their own self-evident status as the most perfectly entitled form of urban transport.

This piece first appeared at The Ubanophile.

Google the phrase “fly-over state.” You will find some unkind and a few nasty characterizations of the states that occupy the middle of the country. Nobody goes to these boring, unremarkable places with their ignorant people, uncultured lifestyles and awful weather. "Fly-over states" are where people never actually go but just fly over to get from the East Coast to the West Coast where the interesting places are.

Now I don't want to disparage the coastal states or their “cool” cities because I have many friends living and working there that I would never dream of offending. But the truth is that the middle of the country is doing quite well and can look forward to a bright future with unaccustomed, uncharacteristic optimism.

The Great Plains turnabout is robust and pervasive, according to “The Rise of the Great Plains,” a report on the future of the American Great Plains recently released by Texas Tech University. Joel Kotkin, Praxis Strategy Group and Kevin Mulligan of TTU’s Center of Geospatial Technology authored the report, which is accompanied by an interactive online atlas of economic, demographic and geographic data.

Instead of being passed over, the region has surpassed the national norms in everything from population increase to income and job growth during the last decade. After generations of net out-migration, the entire region now enjoys a net in-migration from other states, as well as increased immigration from around the world. Contrary to perceptions of the area as a wind-swept, old-age home, the vast majority of the newcomers are between the ages of 20 and 35.

“The Rise of the Great Plains” concludes that three critical factors will propel the region’s future in the 21st century.

First, the region’s vast resources places it in an excellent position to take advantage of worldwide increases in demand for food, fiber and fuel. The region’s manufacturing prowess and increasing trade savvy can propel it into more global markets.

Second, the hyper-evolution and adoption of advanced technologies has enhanced the development of precision agriculture and energy resources, notably oil and gas previously considered impractical to tap. So, too, the Internet and advanced communications have reduced many of the barriers — socio-economic and cultural — which have isolated the Plains from the rest of the country and the world.

Third, and perhaps most significantly, are demographic changes. The reversal of out-migration means that the region is again becoming attractive to people with ambition and talent. This is particularly true of leading cities, many of which now enjoy positive net migration not only from their own rural hinterlands, but from metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles, Minneapolis, the San Francisco Bay Area, New York and Chicago.

Fly-over states forever? Certainly some of the economic realities and perceptions of the Great Plains will persist. Yet, we can accelerate their demise by choosing to make prudent, generative investments in our infrastructure, businesses, institutions, communities and people. By doing so, we ourselves will be empowered to fly over to opportunities wherever they might be found throughout the world.

Delore Zimmerman is the President of Praxis Strategy Group and Publisher of NewGeography.com. This piece originally appeared in Prairie Business Magazine, January 31, 2013.

|