By Joel Kotkin and Mark Schill

Much has been said about the rootlessness of our two Presidential aspirants, but both men have spent their political lifetimes representing real places and specific constituencies. Newgeography.com has already looked into the realities shaping Senator Barack Obama’s adopted hometown of Chicago. Now we turn to the city that has most shaped Senator John McCain’s career: Phoenix.

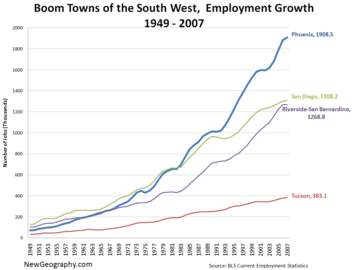

In many ways, Phoenix today is what Chicago was in its earlier days: a rambunctious entrepreneurial town subject to sometimes wild swings in its real estate market. This has led some outsiders to predict that the city --- known for its sprawling development --- is now destined for a long-term decline, a notion that economist Elliot Pollack heartily rejects in his article for us.

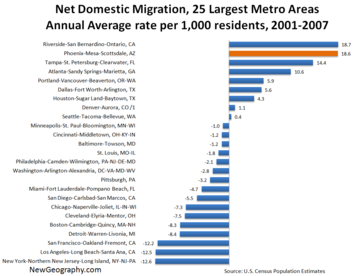

The current decline scenarios for Phoenix echo the “death of suburbia” mantra so eagerly adopted by much of the media and academia since the mortgage crisis and the steep rise in gas prices. A particularly wistful thought in the Great Lakes Region --- Obama’s putative home base --- is that lack of water will force wayward Midwesterns out of places like Phoenix and back up North where they belong.

This is nothing new. Phoenix, as Pollack notes, has been down before, as recently as the early 1990s --- and to quote the old Rodney Dangerfield line doesn’t “get much respect.” Indeed the entire Phoenician ethos has something to do with poking the folks back east (and sometimes us mild weather weenies here in California) in the eye. There’s a maverick, “you can knock me down but never knock me out,” quality that Senator McCain would no doubt relate to but this sentiment is more epitomized by the city’s greatest political figure, the late Senator Barry Goldwater.

To many easterners, Phoenix has never been considered a respectable place to build a city. Arizona, to U.S. Senator Benjamin Wade, was “just like hell, all it lacks is water and good society.” Phoenix’s city fathers included “Jack” Swilling, an often inebriated Confederate Army deserter -turned -promoter, and a sturdy group of Mormon farmers, who shared Swilling’s outsider status, if not his taste for alcohol.

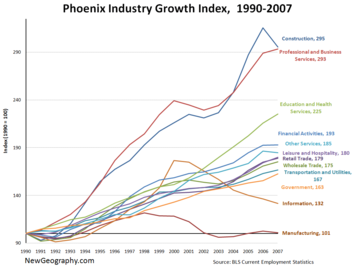

Like Los Angeles, in Phoenix the Second World War accelerated the development of new technology and business service firms. Initially, the desire to base more production further from potentially vulnerable sites on the coasts brought several thousand skilled engineers and scientists to the area. However, later, the city itself --- its low-density lifestyle, its brilliant sunshine, its lack of social constraints --- brought waves of high-technology firms to the region.

By the turn of the century, the city not only ranked among America's fastest growing cities, but also as one of the most attractive to burgeoning high technology and business service firms. In its development pattern, Phoenix essentially followed the model of Los Angeles, but without the beaches, Hollywood or Caltech.

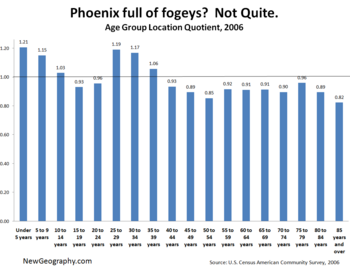

Like its Californian counterpart, Phoenix epitomized all the clichés of plasticity and impermanence associated with the new American city. In addition, like Los Angeles before it, Phoenix gathered in ambitious newcomers seeking a better life. In the 2000 census, almost a third of residents had arrived only five years or less before.

Local entrepreneur Deb Weidenhamer, who came to the Valley of the Sun in 1970 and opened an auction business, says the rapid growth and basic openness to newcomers has created unprecedented opportunities for her. “We came with nothing,” she recalls.” We came here because it had wealth that was increasing. You can find opportunities. People come here for a new start and come with ambitions. Longevity here does not matter here. You can be here ten years and it’s like you’re an old fogy – in the east coast you’d be like a newcomer.”

Virtually all of Weidenhamer’s employees, she notes, also come from outside the region. They create what she calls a “multiplier” effect, with each person bringing new ideas and new energies. “In San Francisco or New York you would have to compete with entrenched companies. Here you can always market the new people,” she suggested at her crowded warehouse. “There’s always a new zip code to service.”

Much less impressed, however, have been many leading urban thinkers, including many local dignitaries. Its sprawling array of separate districts and its relatively weak downtown has led some critics, like the prominent new urbanist Andres Duany, to conclude that Phoenix is a place where “civic life has ceased to exist.” Duany, like Ralph Waldo Emerson a century earlier, hailed Boston as an example of a superior kind of community.

Yet for America’s urban future, it is likely that Phoenix, not Boston, or even Chicago, represents the predominant form of the multi-polar flexible metropolis. Like many older metropolis, Chicago and Boston have been either losing residents --- particularly middle class families --- or growing slowly over the last decade. At the same time, virtually all the fastest growing cities have been places like Phoenix - chock-full of kids and thirty-somethings. That tells you something. As Pollack puts it, “People vote with their feet.”

great post

excellent. one of the best articles I have every read. This is the information which I have been searching. Great information. Ecopolitan EC | Ecopolitan EC price | Ecopolitan | Ecopolitan Punggol | Ecopolitan Executive Condo | Sea Horizon | Sea Horizon EC | Sea Horizon Executive Condo | Sea Horizon Executive Condominium | Sea Horizon Pasir Ris | Sea Horizon EC price | Tembusu Condo | Tembusu at Kovan | Tembusu Kovan | Tembusu condo Price | Tembusu | Vue 8 residence | Vue 8 residence price | Vue 8 Condo | Vue 8 Pasir Ris | Vue 8 | the inflora | inflora condo | inflora loyang | inflora this article is worth bookmarking. keep it up !