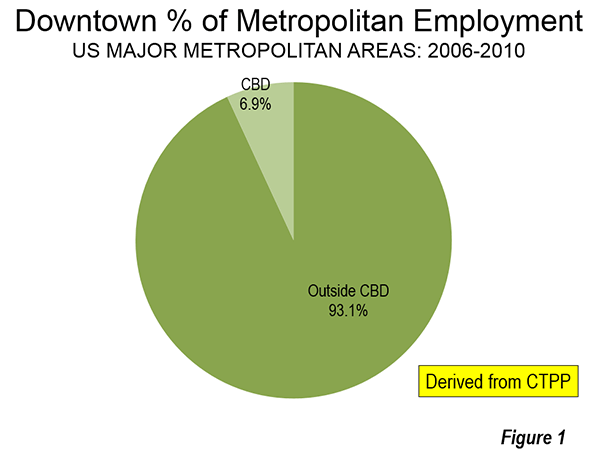

Photographs of downtown skylines are often the "signature" of major metropolitan areas, as my former Amtrak Reform Council colleague and then Mayor of Milwaukee (later President and CEO of the Congress of New Urbanism) John Norquist has rightly said. The cluster of high rise office towers in the central business district (CBD) is often so spectacular – certainly compared with an edge city development or suburban strip center – as to give the impression of virtual dominance. I have often asked audiences to guess how much of a metropolitan area's employment is in the CBD. Answers of 50 percent to 80 percent are not unusual. In fact, the average is 7 percent in the major metropolitan areas (over 1,000,000) and reaches its peak at only 22 percent in New York (Figure 1), which sports the second largest business district in the world (after Tokyo).

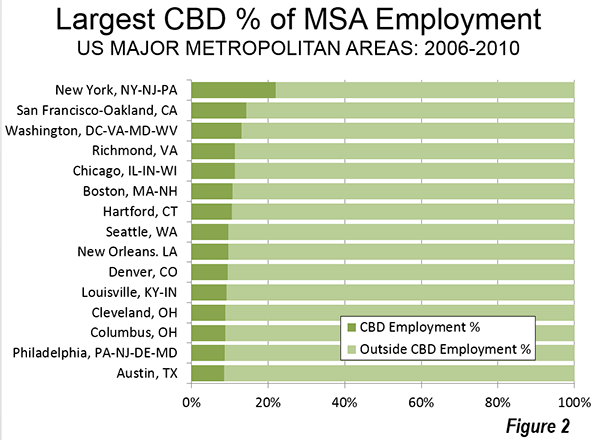

Only seven of the 52 major metropolitan areas have CBDs with 10 percent or more of employment. Some are much lower. For example, Los Angeles and Dallas have had some of the nation's tallest skyscrapers outside New York or Chicago for decades, yet these downtowns have only 2.4 percent and 2.3 percent of their metropolitan area employment respectively (Figure 2).

This and similar information has been summarized in the third edition of Demographia Central Business Districts, which is based on the 2006-2010 Census Transportation Planning Package, a joint venture of the Census Bureau and the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). The two previous editions of the report summarized data from the 1990 and 2000 censuses.

The Declining Role of Downtown

Downtowns have become far less important than before World War II, when a large share of American households did not have access to automobiles and when employment was far more concentrated than today. Indeed, the highly concentrated American downtown area is "unique," as Robert Fogelson indicates in Downtown: Its Rise and Fall: 1880-1950, and could be easily located as the destination of the "street railways." Downtown was a product of transit and remains transit's principal destination today. The concentrated US style CBD form is really quite rare outside other new world nations, such as Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. Some, but only a few Asian cities have also followed the example, most notably Shanghai, Hong Kong, Nanjing, Chongqing, Singapore, and Seoul.

The US, however, for all its role as originator of the downtown paradigm has also led the world in employment dispersion. This reflects the dominance in the US of automobiles. Dispersion is more amenable to mobility by the car, which dominates motorized mobility in virtually all major metropolitan areas of North America and Western Europe. This has led in the US to generally shorter work trip travel times and less traffic congestion, according to Tom Tom and Inrix. The continuing expansion of working at home could improve the situation even more.

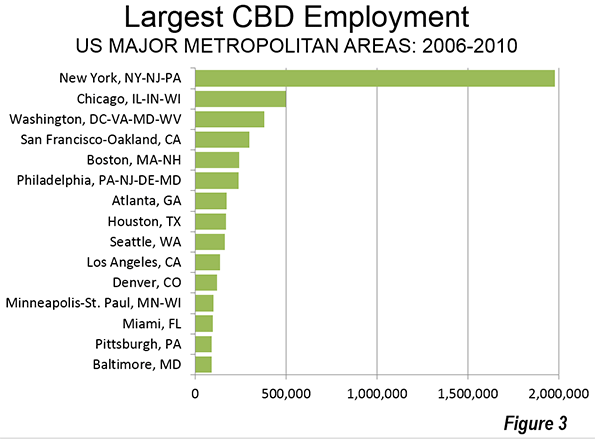

New York has the largest CBD in the nation by far, with nearly 2,000,000 jobs. Chicago's CBD (the Loop and North Michigan Avenue) has about one-quarter as many jobs (500,000) and Washington approximately 375,000. San Francisco, Boston and Philadelphia, also ranked among the nation’s transit "legacy cities," have between 200,000 and 300,000 jobs. Automobile oriented Houston and Atlanta are the largest otherwise, with Houston's downtown being much more compact than Atlanta's. Atlanta's downtown has expanded strongly (and less densely) to the north and includes "Midtown" (Figure 3)

Transit is About Downtown

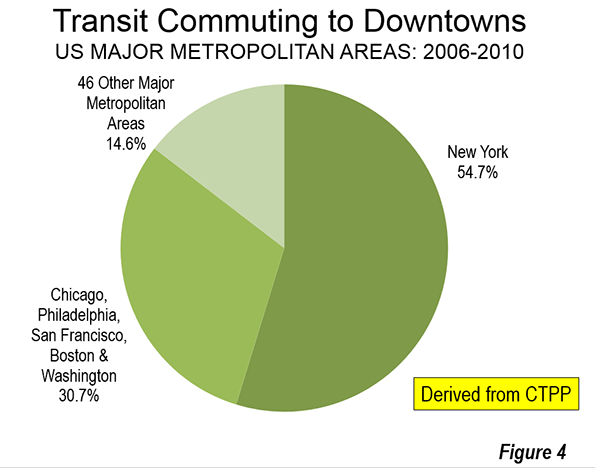

Transit is about downtown. Approximately 55 percent of transit commuting in the United States is to jobs in just six municipalities (not to be confused with metropolitan areas), which I have called transit's "legacy cities." Most of that commuting is to the six downtown areas. Of course, the city of New York is dominant, which alone accounts for 55 percent of the country’s CBD transit commuting (Figure 4), with much of the balance in the other five legacy cities (Figure 4). Only 14 percent of the CBD commuting is to the other 46 smaller downtowns.

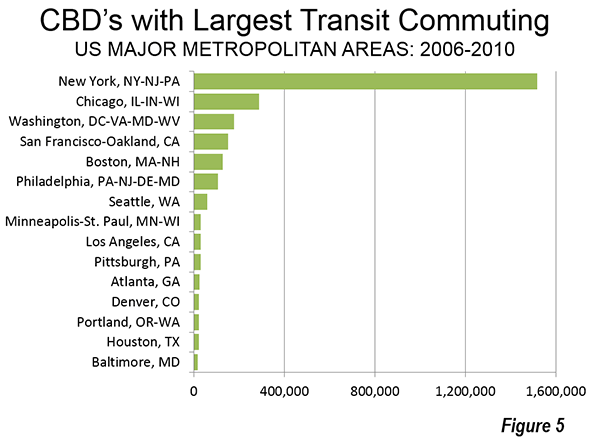

More than 1.5 million transit commuters converge on jobs in Manhattan every day. In the other five legacy cities, the figure ranges from 100,000 to 300,000 daily. All of the other central business districts draw fewer than 100,000 daily commuters. Seattle ranks 7th, at 60,000, and has double or more the CBD transit commuters of any of the other 44 CBDs (Figure 5).

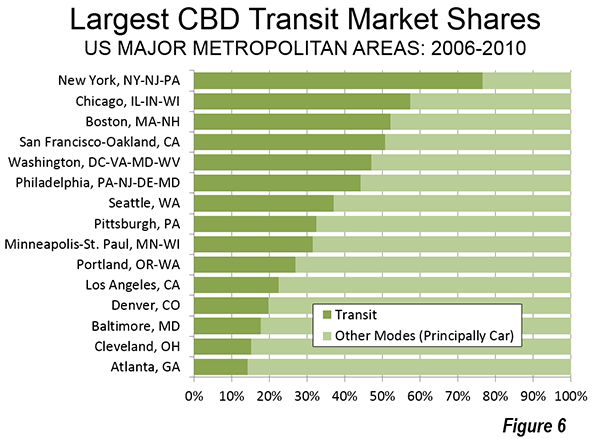

New York has by far the highest transit commuting share of any downtown in the nation. Approximately 77 percent of people who work in the New York central business district commute by transit. The other legacy cities post impressive market shares as well, though well below those of New York. The CBDs in Chicago, Boston, and San Francisco draw between 50 percent and 60 percent of their commuters by transit. Downtown Philadelphia and Washington attract more than 40 percent of their commuters by transit (Figure 6).

Transit is About Downtown II

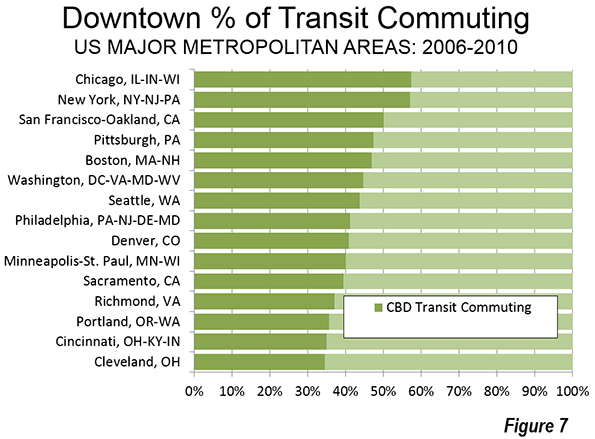

The importance of downtown to transit is also indicated by its predominance in transit commuting destinations. In the New York metropolitan area, with a transit market share of approximately 30 percent, 57 percent of all transit commuting is to downtown jobs. Chicago's transit commuting is concentrated in downtown to a slightly greater degree than in New York. One half of all the transit commuting in the San Francisco metropolitan area is to downtown. The CBDs of Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington account for between 40 percent and 50 percent of all transit commuting in their downtown areas. Seattle and Pittsburgh also are in this range (Figure 7). Seven of the eight metropolitan areas with the largest transit market shares have a CBD commuting dominance of 40 percent or more (Pittsburgh is the exception).

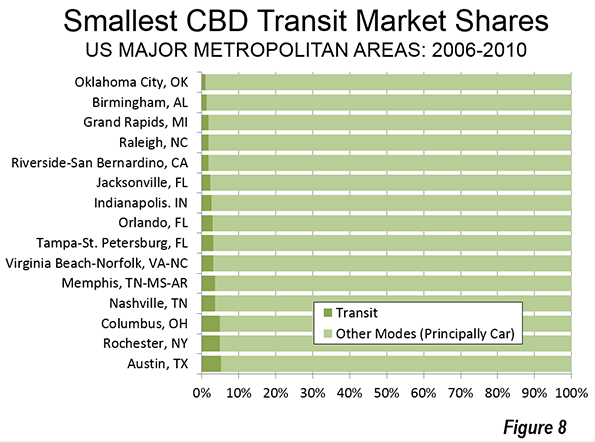

The 52 major metropolitan area CBDs combined have less than five percent of the nation's jobs. Elsewhere, downtowns and otherwise, the other 95 percent of American commuters use transit at only a three percent rate.

Other Employment Centers

In a new feature, Demographia Central Business Districts also provides data for selected employment centers other than the principal central business districts. These also include some surprises. For example, downtown Brooklyn, long since engulfed by the expansion of New York, has the second highest transit market share of any employment center identified other than New York, at 60 percent. Across the river, the Jersey City Waterfront area achieves a transit market share of more than 50 percent, greater than the downtowns of legacy cities Philadelphia and Washington.

Data on supplemental employment center and corridor data is selected and therefore not representative. It is notable that some employment corridors and centers have employment totals that dwarf those of the principal downtown areas in their respective metropolitan areas, such as Los Angeles, Portland, Dallas, and Kansas City.

With a few exceptions, the transit commuting shares for most of these selected centers and corridors is modest. Many are served by new rail systems, which are simply not up to the task of providing mobility to these dispersed centers. Nor can they provide the radial, high quality service that makes transit such a success in the six legacy city downtowns. For example, the Dallas light rail system provides service along virtually the entire US-75 corridor from north of downtown to Plano. Transit's share of commutes in this corridor is only 2 percent, far below the downtown Dallas share of 14 percent and the legacy city downtown average of 65 percent.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He was appointed to the Amtrak Reform Council to fill the unexpired term of Governor Christine Todd Whitman and has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

CBD Employement

In big cities we have found big opportunities to grow; therefore huge numbers of people are migrated towards big cities in searching for better opportunities and hope. As the percentage of employment rate is quite high in big cities in comparison to small towns; so we have found more number of population in big cities. But in reality this migration will directly and indirectly affect the city's economy system; people or job seekers are also able to getting jobs through CBD "central Business District".

Business Coach

Chicago's Central Business District

According to the data, a slightly amazing sixty-three thousand(63,000) jobs have been added to Chicago's CBD since the end of the Great Recession. This now puts Chicago's CBD employment number at just over 540,000.

Let's also remember that a

Let's also remember that a strong force to concentrate "development" downtown is that the more units per sq foot, the more a project is worth. Los Angeles tried to turn Hollywood into a "downtown" with high rises and practically BKed the entire city by giving massive tax subsidies to entice developers to Hollywood.

By placing mixed-use houses next to subway stations, they did not stop to realize that they were also putting mixed-use projects in R-1 and R-2 neighborhoods. That devastated Hollywood -- so much so that council district 13 where they tried to make a downtown like Manhattan near the subways drove out so many people and businesses, that CD 13 literally ceased to qualify as a legal council district.

Hollywood has basically 2 council districts with CD 5 having a tiny bit at the western end. C D had to steal land and people from its neighbording council district in order to be large enough to qualify -- a 1925 Law requires LA to have 15 districts. CD 4 which was away from the "Manhattanized," added population and housing prices are above $1 M -- for R-1 homes build before 1930.

In the Garcetti Flats part of Hollywood, they literally could not give away the condos in the new W Hotel. The massive Hollywood-Highland Project lost close to $1/2 Billion. No one knows how many hundreds of millions of tax dollars Garcetti squandered in Hollywood trying to turn it into Manhattan, but it is probably well over $1 Billion. It's not cheap to destroy a city.

Hollywood is a mess -- the judge who rejected the Hollywood Community Plan asked, How did this plan get so far off track?

The answer is simple -- corruption. In his delusion that all he had to do was use tax dollars to subsidize high rises, Garcetti ignored all the laws (as the judge noted) and made Hollywood such a nightmare, that people simply left.

Now that Garcetti is mayor, he is doing the same thing with the real DTLA --

Post-industrial politics

(This was meant as a reply to previous comments--I missed the "reply" button)

The political machines in the old cities catered to the short-term impulses of the urban poor for generations in exchange for reliable block votes. The social costs of continuing that policy in the post-industrial economy are now evident, the bills are being presented, and the city machines don't want to pay them. Instead, they now want these huge numbers of the poor to move to the suburbs, so that large areas of the cities can be developed into high-rent playgrounds for the affluent.

They want this to happen without these groups having assimilated or increased their earning power. This is radically different from what happened with previous waves of urban poor, whose perceptions of economy and society were not distorted by the welfare-state politics that took the place of the old patronage politics (where the reward for the little guy was often a manual-labor job), and who could move out into a healthy industrial economy that could accommodate newcomers in much of the country. The city machines, and aspiring urban developers, want to speed up the process with policies designed to push the poor out of the cities and force their accommodation in regions that have absolutely no economic place for them.

The fact remains that only in the cities can these groups be accommodated in the style to which they have become accustomed.

Not quite...

The Industrial and the Post-Industrial Region have two fundamentally different forms. The Industrial Region consisted of a single center usually organized around a port or major railroad intersection that could import coal and distribute it to nearby factories. The centering effect of ports and railroads meant that regions were organized like spokes, with growth emanating from a single point. The periphery might be populated with small rural towns, but the majority of the region's population, economic activity and power was concentrated within the city limits. In this organization, the poor lived in the central neighborhoods while the middle and upper income folks inhabited the surrounding suburbs.

The Post-Industrial Region is dispersed with multiple concentations of economic activity organized around highways. The majority of a region's economic activity, population and power now exists outside of the old city in the suburban and ex-urban towns. Even with this completely different form and power dynamic, the pattern of a region's poor living in center city neighborhoods and increasingly in inner suburbs while the middle and upper income people live in outer suburbs and ex-urbs has remained. For the poor, the region is still limited to the old industrial city, yet there is a whole other region available to middle and upper income people - resulting in a highly stratified, segregated and hierarchical region.

Cities are no longer the sole providers for regions, and haven't been since 1960. It's been 50 years of suburbs and ex-urbs reaping the benefits of highway-oriented development without providing for their share of the region's population.

In the Post-Industrial economy, the largest obstacle to employment is transportation - people simply cannot get to where the jobs are. The solution to this isn't to continue the organization pattern of the Industrial Region where rings of increasing wealth radiate from the old central city. The solution is to make the entire region accessible for everyone by 1) building mixed-affordable housing where concentrations of jobs are, and 2) expand transit along circumferential routes connecting areas with concentrations of jobs and new housing.

Coincidentally, this would open up inner city neighborhoods for development, thus allowing higher income folks to move in, but cities would still be home to their proportion of the region's poor, which is all that can be reasonably expected from any place. It's not 1920 anymore, cities cannot be home to 50%+ of a region's poor when they contain only 10% of the population. There needs to be a massive balancing of responsibility in the Post-Industrial Region to reflect the pattern of job, population and power shift that has occurred over the last 50 years.

The Central Business

The Central Business District is but one of many business districts within a Metropolitan Area, labor market, region, etc. A worthwhile discussion would be one that compares different Business Districts within a region, not compares regions to one another because there is greater diversity within regions than between them.

Typically, the highest wage jobs are in the CBD and they are held by people living outside the municipality where the jobs are located. Conversley, the lowest wage jobs are disproportionately located in suburban shopping centers that inner city workers reverse commute to. Effectively, the CBD provides jobs for the wealthiest suburban residents, while the suburbs provide jobs for the poorest city dwellers because that is where the most affordable housing and transportation are. The city foots the bill for all the consequences stemming from having large concentrations of poor people, while suburbs reap the benefits of commuting into the CBD for high-wage jobs.

Metropolitan regions are places of segregation, stratification, spatial hierarchy, and disproportionate provision. The cities provide a disproportionately large share of the region's jobs per capita, while servicing a disproportionately large share of the region's working poor.

It would be interesting to look at the number of jobs per acre, jobs per capita, wages paid, and other indicators of how the CBD performs relative to other business districts within the region, which might be spread over thousands of strip malls, office parks, old town centers, and neighborhood thoroughfares throughout the region.

Once you remove your bias, you quickly realize the important characteristics of CBD's like:

-7% of a region's jobs are provided for on 1% of the region's land

-Cities have more jobs than workers, yet house more unemployed and welfare recipients than suburbs because cities import high-wage workers and export low-wage workers in the morning, then watch as paychecks leave the city and low-wage workers needing supplemental food assistance return in the afternoon

-In many ways, CBD's function as edge cities organized around automotive transport

If metropolitan regions were trully polycentric, then suburbs would provide more high-wage jobs, and housing and transportation options for the working poor, and cities would house a larger number of upper income residents. This contrasts with what exists today in our highly segregated and hierarchical regions.

Physical determinism versus real people's needs

There is a term, "physical determinism", that has been used to describe the belief that urban form itself is the cause of the income levels generated by the businesses and people located therein.

I like "cargo cultism" as a term to describe the same thing.

Would you argue that the rural sector should be located in tall-building CBD's served by transit because that would result in an increase in incomes?

It is only slightly less stupid to suggest that all non-rural economic sectors should also do so.

I recommend Robert Fishman's "Megalopolis Unbound" as an education in the co-related evolution of technology, the economy, and urban form.

I also recommend William Fruth's "The Flow of Money and its Impact on Local Economies". One of the points he makes is that some income sources relate to wealth creation and others to wealth transfer. CBD's are mostly based on wealth transfer. Wealth creation mostly occurs in lower density locations. You can't base your entire nation's cities on wealth-transferring employment like finance and bureaucracy. Most of your cities have to be free-wheeling powerhouses like Houston.

The UK is probably the world's "luckiest" economy in terms of earning a high proportion of primary economic income via wealth transfers from the global economy rather than just its national one - in the form of fee income by London's finance sector. But "trickle down" has miserably failed to help the bottom 80% of the population who desperately need employment of the sort that a Houston would provide - but the UK's urban planning system prohibits anything like Houston, or even Silicon Valley, from evolving. The cost of space for living is a disgrace; their housing is as expensive as Boston for something like 8 times as dense forms of living.

The pre-industrial economy

The pre-industrial economy of the crafts, maritime trade and agriculture produced a landscape of self-sufficient towns connected by water ways and surrounded by a loose ring of villages and hamlets. Each settlement pattern - town, village and hamlet - housed its own rich and poor.

The industrial economy of manufacturing, trade and finance produced a landscape of cities connected to one another by railroads. The cities were made up of downtowns connected by light-rail to suburbs and rural towns. Ethnic and class enclaves emerged in this arrangement with the poor living around the edge of downtown and wealthier areas surrounding.

The post-industrial economy of service and finance has produced a landscape of the old monocentric city surrounded by edge cities and everything connected with highways. Urban renewal turned downtowns into central business districts, inner suburbs into slums, outer suburbs into static artifacts, and pushed growth predominately to the ex-urban edge. Despite the old city no longer being the sole center of the region, it still houses a disproportionate share of the region's poor.

In today's dispersed, decentralized metropolitan landscape, cities should not be expected to house the region's poor as they did a century ago. Ex-urbs can't grow a disportionate number of low-wage jobs in the retail sector and continue to expect inner suburbs to continue housing these workers. Every municipality within a given metropolitan region should provide for their proportion of the region's population. Segregation should not be a viable development pattern anymore.

Cities should not be expected to perform the same duties in today's metropolitan landscape that they did a century ago when they were the sole center of the region.