NewGeography.com blogs

Economist Clifford Winston of the Brookings Institution outlines the surface transportation system of the future in a Wall Street Journal commentary, "Paving the Way for Diverless Cars." Winston notes "a much better technological solution is on the horizon" than high speed rail "as an effective way to reduce highway congestion" as the Obama administration in Washington and the Brown administration in Sacramento contend. Indeed, not even the voluminous planning documentation used to justify high speed rail provides evidence that the 21st century edition of an early 19th century technology can materially reduce traffic congestion.

Already Google has conducted experiments with the automated car that have been so successful that they are now permitted in Nevada. Winston suggests that by automating cars, it will be necessary to separate automobile traffic from truck traffic, which will make it possible to provide additional traffic lanes within the existing road footprint. Non-automated cars and trucks would continue to operate in conventional, wider lanes on the same right-of-way. Another advantage would be that with the automated control, more cars could be accommodated in each lane. The need for highway expansion would be largely displaced by substantially improving capacity by upgrading highways with 21st century technology.

Winston has been a critic of overly expensive urban rail systems and transit subsidies. Driverless cars were also the subject of a Wall Street Journal commentary by Randal O'Toole in 2010.

Big cities have been on a bit of a roll in recent years. But sometimes you can have too much success, as we may be seeing in the case of New York. This week the New York Times reported that finance firms are moving mid-level jobs away from Wall Street to places like Salt Lake City and Charlotte.

There’s a lot going on here. First, a lot this is driven by New York’s success, not its failure. New York is increasingly valuable as a site of high end production. As a result, lower value activities get squeezed out and replaced with higher ones. Despite the exodus of Wall Street jobs, New York City has been booming, and a stat from last year showed that the city was within 60,000 jobs of its all time employment high. This sort of churn is somewhat normal when high value and lower value economic geographies come into contact within the same physical space, as I noted regarding California in “Migration: Geographies in Conflict.”

It might be tempting for city leaders to actually celebrate this, but they shouldn’t. In a city that is desperate for middle class jobs, these are white collar middle class positions that are being lost. New York has stunningly high levels of income inequality – Joel Kotkin has noted it is the same as Namibia’s – and this can’t be making it any better.

Also, is there any precedent for a city being successful and dynamic, over a longer term purely as a production center for ultra-high end activities (with perhaps an associated servant class)? Sure, places like Aspen can do it. Imperial capitals seem to have been able to do something of the sort. Perhaps that’s how New York’s leaders like to see their city, but they are taking an awful risk.

New York is too concentrated in high end activities already, notably the high end of finance, as Ed Glaeser noted in his article “Wall Street Is Not Enough.” This renders it extremely vulnerable to downturns in that sector.

It might seem like exporting finance jobs would be part of that re-balancing, but when they are lower end positions, all you are doing is re-concentrating finance at more elite levels. Because to these types of businesses cost is almost literally no object, they have driven the cost of New York real estate through the roof.

When one industry becomes super-dominant in a neighborhood, Jane Jacobs noted it could lead to a situation she called “the self-destruction of diversity,” where a particular type of user – generally banks – gobble up the land and ultimate sterilize what formerly drew them to the area.

I wrote about this in regard to Chicago in a speculative piece called “Chicago: Corporate Headquarters and the Global City” in which I note a flow of corporate headquarters back into global cities, albeit reconstituted executive headquarters only).

This puts the bigger cities in a tough spot. They have to continue to go up the value chain because smaller cities are rapidly eroding their competitive advantage at lower ends. Ultimately we’ll see where this leads but I don’t think it’s healthy in the long term at all. Figuring this out is just one piece of the rebuilding our overall economy for the 21st century that needs to be accomplished.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs based in the Midwest. This piece originally appeared at The Urbanophile

The Economist reminds readers of the economics of housing (or for that matter, oil or any other good or service): constraining the supply of a good or service in demand raises its price. In a 14-page feature on London, The Economist decries the high cost of housing in London. And, for good reason, the 8th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey showed London to have a median multiple (median house price divided by median household income) 6.9 in the fourth quarter of 2011. This figure, which would be more like 3.0 in a normally functioning market, is exceeded by few other major metropolitan areas, though Hong Kong, Vancouver, Sydney are more unaffordable.

The Economist noted that:

... perhaps the biggest constraint on development in London is the Green Belt. Established after the war, it runs (with perforations) all around London, to a depth of up to 50 miles, and bans almost all building on half a million hectares of land around the city.

Not only has this constraint led to higher house prices, but it has resulted in greater urban expansion and imposed greater costs, in time and money on commuters.

... it has pushed it into the greater south-east, thus spoiling the countryside across a bigger area. It has also raised the cost of housing and forced workers to travel farther. Commuting costs in London are now higher than in any other rich-world capital.

One alternative is to relax the Green Belt controls. The Economist points out that allowing development one mile into the Green belt would add one-sixth to the developable area of London. The Economist also notes that "far more than would be needed to make a huge difference to housing availability" and that opening the Green Belt "might not be an environmental disaster."

The Economist calculates that "the average London worker can buy half an average home." Britain would gain if the interests of those with a stake in a poorer middle class and greater poverty were to finally give way to the general welfare.

The Oregonian reports that suburban Hillsboro's first mixed use condominium development is no more. Washington Street Station, was built near the suburb's small but historic downtown (see Note on Hillsboro).

The project was opened in 2009, one block from the Hillsboro Central station on Portland's Max (photo) light rail line. The four floor building, located in a generally low-rise residential area with detached housing, was to have had commercial development on the street floor and owner occupied condominiums on the top three floors. But the market was not there. As 2012 began, none of the 20 units had been sold.

At that point, new owners decided to convert the condominiums to rental units and to convert the first floor commercial space into apartments as well.

Local planning officials indicate no concern about converting the condominium development to rental units, or the loss of the first planned mixed use development in the city. The Oregonian article indicates, however, that a soon to be built development, located just blocks away, will be required to remain mixed use for at least 30 years.

------

Note on Hillsboro: Hillsboro is typical for a mid-20th century exurb that has been engulfed by the expansion of a growing urban area. In 1950, the Portland urban area had a population of 500,000 (density 4,500 per square mile or 1,750 per square kilometer ), and Hillsboro was a compact exurb with less than 5,000 population, located outside the urban area. Today, the Portland urban area has approximately 1,850,000 residents (density 3,500 per square mile or 1,350 per square kilometer). Hillsboro, which is inside the urban area has more than 90,000 residents, most of whom are beyond walking distance from downtown and have much more convenient access to the big box stores (including the claimed largest "Costco" in the world), shopping centers and strip malls that do most of the retail business. Hillsboro is also the heart of "Silicon Forest" with its information technology manufacturing (such as Intel). As a result, the jobs-housing balance in Hillsboro now exceeds that of Portland according to 2010 American Community Survey data (1.48 jobs per resident worker in Hillsboro compared to 1.45 in the city of Portland).

|

Redaction Notice: September 17, 2012

Part of this article from June 28, 2012 has been redacted because of difficulties with the US Census Bureau's 2011 sub-county population estimates. In fact, these were not genuine population estimates at all, but were largely "fair share" allocations of county population change rates based upon the share of population in each jurisdiction. This issue is further described at was revealed on newgeography.com by Chris Briem and our new URL.

However, the fact remains that domestic migration trends continue to be from historical core cities to the suburbs, as the unredacted data below indicates.

|

Just released United States Bureau of the Census estimates indicate that the urban cores of major metropolitan areas (over 1,000,000) grew slightly faster than their suburbs between July 2010 and July 2011. Overall, the historical core municipalities grew 1.03 percent, compared to the suburban growth of 0.93 percent. Among the 51 metropolitan areas, 26 urban cores grew at a faster percentage rate than their suburbs (Note 1). However, suburban areas continued to add many more people. Over suburban areas grew 1,150,000, compared to 462,000 for the urban cores, indicating that approximately 75 percent of new residents were in the suburbs. Suburban areas had greater population growth in 43 of the 51 metropolitan areas (Table 1).

As was noted in Still Moving to the Suburbs and Exurbs, the core counties of US metropolitan areas, which contain the greatest portion of the historical core municipalities (Note 2) also grew faster than suburban counties between 2010 and 2011. However, that is not an indication of an exodus from the suburbs to urban cores.

Migration Continues from Cores (County Data)

There was net domestic migration (people moving between counties of the United States) of minus 67,000 in the core counties, while a net 121,000 domestic migrants moved into suburban areas between 2010 and 2011. The stronger core growth was driven by stronger international migration and a larger natural growth rate (births minus deaths).

Limited City Data Confirms the Trend

Migration data is not reported below the county level. As a result, historical core municipality migration data is not available, except where cities and counties are combined. A review of such cases confirms the finding from Still Moving to the Suburbs and Exurbs(Table 2). Among the 12 combined city/counties, there was a net domestic migration loss of 49,000 in the historical core municipalities, while there was a much smaller net domestic migration loss of 1,000 in the corresponding suburban areas.

|

Note: Table 2 is retained since the Census Bureau produced genuine population estimates for counties. Table 2 includes only municipalities that are coterminous with counties, and thus were not subject to the "fair share" population growth allocation method inappropriately applied at the sub-county level. |

| Table 2 |

|

|

| Historical Core Municipality Domestic Migration 2010-2011 |

| (Where Cities and Counties are Combined) |

|

| |

Central City/County |

Suburban Counties |

| PRE-1950 CITY/COUNTIES |

(55,441) |

(21,306) |

| Baltmore |

(3,638) |

2,297 |

| Denver |

8,281 |

11,284 |

| New York |

(56,982) |

(41,993) |

| Philadelphia |

(5,466) |

(7,667) |

| San Francisco |

416 |

5,464 |

| St. Louis |

(4,959) |

(5,301) |

| Washington |

6,907 |

14,610 |

| |

|

|

| POST-1950 CITY/COUNTIES |

(4,119) |

20,179 |

| Indianapolis |

(3,401) |

5,341 |

| Jacksonville |

(1,485) |

4,396 |

| Louisville |

18 |

1,868 |

| Nashville |

749 |

8,574 |

| |

|

|

| NOT CLASSIFIED (Due to Hurricane Katrina) |

|

|

| New Orleans |

10,243 |

(90) |

| |

|

|

| TOTAL |

(49,317) |

(1,217) |

- Among the seven combined city/counties formed before 1950 (excluding New Orleans), the historical core municipalities had a net domestic migration loss of 55,000, while the suburban areas had a smaller net domestic loss of 21,000. In four cases, the historical core municipalities had domestic migration losses. In the three cases in which cities had domestic migration gains, there were also domestic migration gains in the suburbs. In this group, New York had a domestic migration loss of 57,000 despite having an overall population gain of 55,000 (the gain resulting from international migration and natural growth)

- Among the four combined city/counties formed after 1950, the historical core municipalities had a net domestic migration loss of 4,000, while the suburban areas had a net domestic migration gain of 20,000. In two cases, the historical core municipalities had domestic migration losses. In the two cases in which cities had domestic migration gains, there were also domestic migration gains in the suburbs.

- New Orleans is a special case, by virtue of the fact that it is "still rebounding from the effects of Hurricane Katrina," according to the Bureau of the Census and remains 20 percent below its 2005 population. New Orleans is the only case that meets the requirement of historical core net domestic migration gain and suburban net domestic migration loss to demonstrate the likelihood of movement from the suburbs to the city. The historical core municipality had a net gain of 10,000 domestic migrants, while the suburbs lost 90, which could indicate that a very small number of people moved to the city from the suburbs (Note 3).

Moreover, the county data indicates that in 25 of the 49 metropolitan areas with suburban counties, core counties lost domestic migrants between 2010 and 2011.

The Effect of "Staying Put"

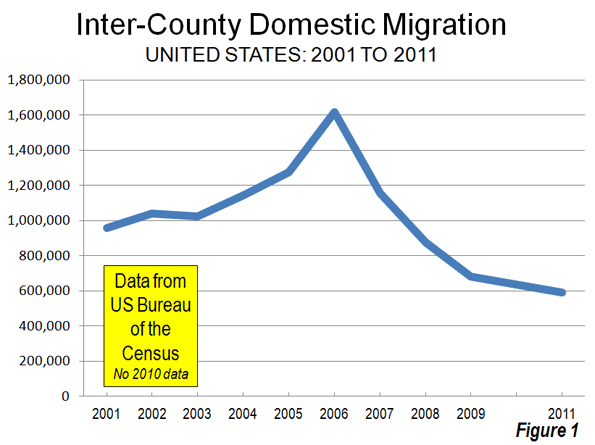

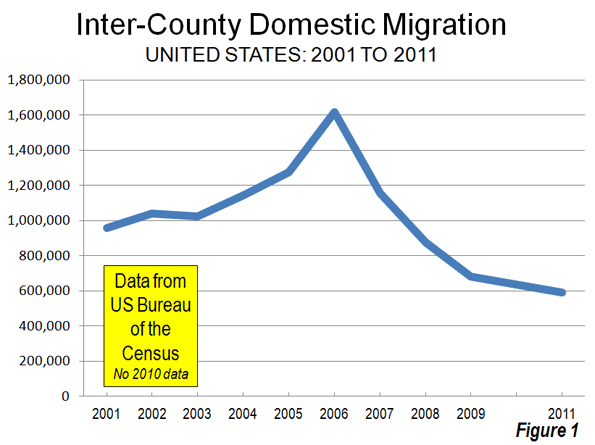

As with the previously released county population estimates, the city data that is available indicates that Americans are staying put in the difficult economy. Domestic migration has fallen substantially. Over the past year, 590,000 people moved between the nation's counties. This domestic migration compares to an annual average of 1,080,000 between the 2000 and 2009 (Figure 1). This reduction in domestic migration has made international migration and natural growth more prevalent, and as a result, core growth has been stronger.

Note 1: An article in this morning's Wall Street Journal contains information different from this article. The Wall Street Journal article classifies some cities as urban core that this article defines as suburbs (such as Fort Lauderdale [Miami], Aurora [Denver] and Arden-Arcade [Sacramento]). This article defines urban cores as historical core municipalities.

Note 2: All historical core municipalities are principally in one county, except for New York (city), which is five counties.

Note 3: The Bureau of the Census domestic migration data is limited to a net number for each county, so it is not possible to determine where people are moving to or moving from.

|