Transit ridership is increasing in the United States. The American Public Transportation Association (APTA) has reported that 10.8 billion trips were taken on transit in 2014, the largest number since 1956. With a more than 80% increase in gasoline prices since 2004, higher transit ridership was to be expected. However, it would be wrong to suggest the transit ridership is anywhere near its historic peak, nor that the increases have been broadly spread around the nation.

Highest Ridership Since 1956 (Which was the Lowest Since 1912)

Total transit ridership in 2014 was the highest since 1956. That's just the beginning. The 2014 modern record ridership was lower than every year from 1956 all the way back to at least 1912, the last year of William Howard Taft's presidency, when transit carried 13.2 billion riders.

Transit ridership has virtually collapsed since that time in relative terms. In 1912, the average man, woman and child rode transit at least 170 times a year. Today, the figure is about 35, down 80% from 1912. During the intervening century, non-farm employment increased by more than five times and the urban population, transit's principal market, also increased more than five times. Ridership was elevated to its peak by gasoline rationing during World War II. Before that, transit ridership had peaked in 1926, as car ownership and suburbs rose before the Great Depression.

The Continuing Dominance of New York

Further, contrary to some media accounts, recent transit increases have not really been national in scope. Nearly all of it was on transit systems that serve local mobility in the City of New York as well as the rail systems serving the City from the suburbs. In the City, most of the service is provided by the Transit Authority. Additional services are provided by the New York City Department of Transportation and the Staten Island Railway. The suburban rail systems are the Long Island Railroad, the Metro North Railroad, New Jersey Transit Rail and PATH Rail. On these systems, nearly 90% of national work trip travel was to the city of New York and nearly three-quarters of those were to Manhattan.

Transit and New York: The Last Decade

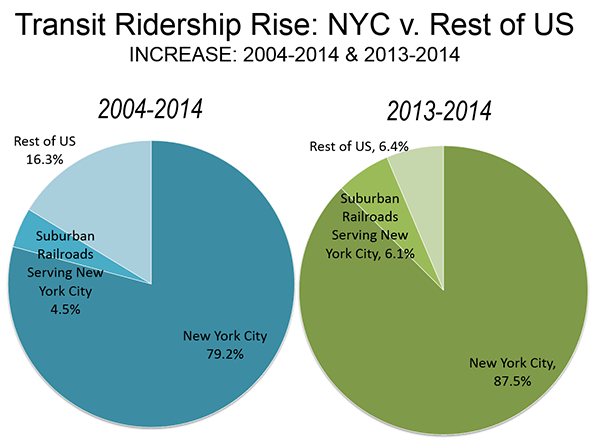

Overall, the enormous system of buses and subways of New York City alone accounted for 88 percent of the national ridership increase from 2013 to 2014. If the ridership on the four large suburban rail systems that serve New York City (the Long Island Railroad, the Metro-North Railroad, New Jersey transit commuter rail, and the PATH trains) is added, City related transit accounts for 94 percent of the increase. A great achievement for the City, but not one that is being repeated in the rest of the nation.

This is nothing new. National transit ridership has increased about 10 percent over the decade since 2004. Much of the increase --- 79 percent --- has been on New York City's buses and subways. The suburban rail systems raise that total to 84 percent. This does not include the many commuter buses that enter the city especially from New Jersey and other suburbs, which cannot extracted from the data because it is not separately reported (Figure).

New York's transit turnaround has been nothing short of impressive. Nearly all of the nation's progress in transit has been on a bus and subway system that carries one third of the national rides.

The results have not been nearly so positive in the rest of urban America, where 30 times as many people live. While New York City related transit services experienced a ridership increase of 33% in the last decade, in the rest of the nation, the increase was less than three percent. Even huge ridership increases in New York City cannot make much of a difference nationally. In 2004, transit accounted for approximately 1.6% of urban travel. By 2014, it had risen to only 1.7%. Without taking anything from New York City's impressive transit record, these results are not likely to be replicated elsewhere. New York City is a very unique place. It is home to the world's second largest business district, after Tokyo, the area south of Central Park in Manhattan. Approximately 2 million peoplework in this small area, a number approximately four times the next largest central business districts, in Chicago and Washington.

Approximately three quarters of Manhattan employees reach work by transit. This is 15 times the national average, New York City's population density (excluding Staten Island, with its postwar suburbanization) is by far the highest and most extensive in the nation. The city of San Francisco comes the closest to New York City, with little more than half the population density and only 1/10 the total population.

Transit is often suggested as a substitute for the car. The reality is that transit can compete with the car only to the largest downtowns. Destinations within the six transit "legacy cities," (not metropolitan areas) of New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Boston, and Washington account for most of the nation's transit work trips. And, 60% of these trips are to downtown.

Transit cannot compete elsewhere, because travel times tend to be double those of the automobile (according to the American Community Survey) and it provides little practical access to most jobs. University of Minnesota research indicates the average employee can reach fewer than 10 percent of jobs in less than one hour by transit in 46 major metropolitan areas. By contrast, approximately 65% of people who drive reach their jobs in less than 30 minutesby car in the major metropolitan areas. Building new rail systems doesn't change the equation. At least 20 new urban rail systems have been built in the last four decades, though transit's percentage of work trips has generally not improved, despite representations about reducing traffic congestion to the contrary. For example, in Portland, Washington, Los Angeles, Dallas-Fort Worth, and Atlanta, which have among the most extensive new rail systems, a smaller percentage of commuters use transit than before rail opened, when there were only buses.

Even low income workers, who are often portrayed as "transit dependent," use cars much more than transit, and at a rate nearly equal to that of others in the labor force.

Yet, transit funding advocates continue to seek even more money, claiming that transit can attract drivers from their cars and reduce traffic congestion. That may be true in New York City's uniquely transit-friendly environment, but not elsewhere.

Wendell Cox was a three-term member of the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission and chaired two APTA national committees. He is a public policy consultant in St. Louis and is a senior fellow at the Center for Opportunity Urbanism.

Photo: Bart A car Oakland Coliseum Station

Our Metros Don't Have Well-oiled Transport Systems As Yet

Comparing the profile of my country, South Africa, to what has been outlined above for New York, I can clearly see why transit ridership will not work for us.

It is so true that a town has to be walkable first to be transit rider friendly. In South Africa nobody walks or uses transit systems, except for the poor who don't have a choice. And yes, our communities do not want 'the poor' so who is really going to invest in friendlier transit systems that actually work and serve everyone?

Forthwith are some reasons why transit systems work in New York but will not work in my country; The New York underground train stations are accessible and one does not need a car to travel from place to place during the day because activities and shops are centralised. Manhattan is friendly, attractive and walkable. In South Africa for example, the Central Business Districts of Johannesburg and Pretoria are dirty, unattractive and completely unsafe. Hobos roam freely and make for themselves a place to sleep on the pavements at night and sleep until 08h00. I don't know what the government is doing about renewal in these places but if you work in the CBD, you want to drive out of town during lunch break or for meetings. Public transport is somewhat a last option because it is a nightmare and safety is a big concern.

The only viable option with regards to public transport is the Gautrain, which only came into existence in 2010 but unfortunately it was designed for the 2010 FIFA World Cup and therefore only meant to cater for the needs of the tourist stadium goer. Pick-up points are hotels, malls and other tourist points of interest. Anyway, it is now being utilized by commuters, but still a very small percentage. Its buses get stuck in traffic and during peak hours it will take you an hour and a half to get to work on the train whereas it would take you 30 minutes by car. In South African metros, car ownership is a must, not an option.

More and more Rapid Transit Systems are being introduced in Gauteng and in Pretoria but I don't see drivers being attracted from their cars and ditching traffic. It is only the poor who will benefit from these system which seem to be designed only for them. The problem with our Metros is that they don't have well oiled attractive public transport systems as yet. Over how many years has the transit system of New York developed? Since before WWII. We are also still a long way.

Sincerely, u15263135

additional reasons why New York distorts the picture

There are three other important factors that make New York City different from almost anywhere else as far as transit use is concerned.

1) Many cities have rivers running through them, and if the rivers are of any size, they form bottlenecks that are significant barriers to commuting. But New York City is basically surrounded by sizable bodies of water. I'm sure that disproportionately few people commute to the Bronx entirely by land from east of the Hudson, or commute to Brooklyn or Queens by land from Long island. Those going by car to Manhattan, or to Brooklyn or Queens from the mainland, must go through the bottlenecks formed by bridges, whose number is small relative to the potential number of car commuters. This can slow the drive immensely. (If EZ-Pass is still bottlenecking the bridge approaches the way it was when I lived there, it the delays will be even greater than they would be elsewhere.)

This factor affects buses as well as cars, but many, if they have to make a long commute in any case, would rather do it sleeping or reading or working on a bus than drive themselves. Trains are much less affected relative to other cities, since they are always limited to a few approaches. Thus the hydrography of the city affects the balance of cost and time in favor of buses and trains.

2) Even for those who can drive in without crossing bridges, the cost and time of the commute is often magnified by the sheer size of the metropolitan area. There are people who commute to New York from Pennsylvania, and farther. This factor, of course, also affects the equation for those who cross bridges. Those who drive in from Long Island to the city core also have to cross a lot of New York City itself.

3) In addition, the parking situation in Manhattan is much worse than in anyplace else in the U.S.

All this tips the balance of cost and time in favor of mass transit to a degree that is hardly typical of the rest of the U.S.

In addition, there's the factor noted by a previous commenter: a large number of people drive much of the way in, often quite a long way, and take the train or bus from there.

One more I forgot...

In the core areas of New York City, more than anywhere else in the country, keeping a car isn't even an option for a lot of people, because of 1) the shortage of parking, 2) alternate-side-of-the street parking regulations, and 3) (unless this has changed) the high rate of car theft.

And another item worth mentioning:

The city's subway system actually works fairly well most of the time, if all you want is to get into and out of Manhattan. One reason for that is that most of those lines were laid out a long time ago, in a very different era, by private companies that were interested in establishing economically viable lines by moving commuters from where they already lived to where the commuters wanted to go. These companies were not interested in speculating on the less substantial forms of social engineering. They operated under the auspices of a city government that probably held the same view. The lines later built by the city were built with the same objective. That's less likely with city-planned lines today.

(I'm far from believing that privatization is always the best way to serve the public, but it can sometimes work out that way if the money is to be made by serving the basic needs of large numbers of people.)

Transit only makes sense after a town is already walkable first

Transit isn't a replacement for cars and highways. Transit augments and connects walkable pedestrian friendly neighborhoods. Transit works beautifully in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Toronto, and a few other places. But if you don't have existing pedestrian neighborhoods than transit will be expensive and completely ineffective.

Here's one way to look at the situation:

We haven't built compact, walkable, mixed use towns since WWII. Adding transit to the post war cul-de-sacs and strip malls of Atlanta, Phoenix, and Houston is a complete waste of time and money and might just degrade the driving experience of the 99.7% of the people who live in these places. Transit is associated with people who can't afford to own a car so transit is for "Them". "They" are not wanted in most communities. So transit is a political non-starter.

Here's another way to look at the situation:

Many aging suburbs are in decline and are losing market value. This is occurring just as the car oriented horizontal infrastructure is failing and needs a complete and very expensive overhaul. The tax base just isn't there to fund these project. So people have two choices. They can migrate to newer suburbs where the infrastructure hasn't started to deteriorate yet and where taxes are still reasonable. Or they can migrate to an historic town center where the pedestrian oriented built environment has enough market value for the tax base to support the required compact infrastructure. Then transit starts to make sense.

Apples and oranges.

www.granolashotgun.com

transit users or parking users?

I am officially a public transit user. I routinely drive 90% of the way to my destination, park in a free lot, and ride light rail a few miles to my destination.

The cost of both light rail rides is considerably less than the cost of actual destination parking and the time is similar, since the light rail puts me closer to my destination than any affordable parking lot.

I know that hundreds of people do this every day just from the parking lot I use.

Meanwhile, the light rail executives are no doubt chalking us all up as "regular transit users" despite the fact that we are really "lower cost parking users".

As an individual, I'm grateful. As a taxpayer, I'm depressed, as I'm certain these light rail executives view this as a feature rather than a bug in their money bleeding system.