Nashville is the 36th largest metropolitan area in the nation, having long since passed historic Tennessee leader Memphis. Nashville was the 10th fastest growing major metropolitan area in 2017. At the current growth rate Nashville will reach 2 million residents by the 2020 census and seems likely to pass slower growing San Jose soon after. Effective transportation is necessary for a growing metropolitan area to maintain its competitiveness. Yet voters are being asked to sink billions into a hopeless rail transit system that could cost more per capita than any in US history.

The key to Nashville’s growth is net domestic migration: many more people are moving in than moving out to other parts of the nation. Just since 2010, the Nashville metropolitan area has attracted more than 125,000 net domestic migrants.

Further, Nashville’s net domestic migration is up from earlier in the decade, averaging more than 20,000 for the last four years, up from under 9,000 in 2011. In contrast, high-flying Denver saw domestic migration collapse from 32,000 in 2015 to just 12,000 in 2017.

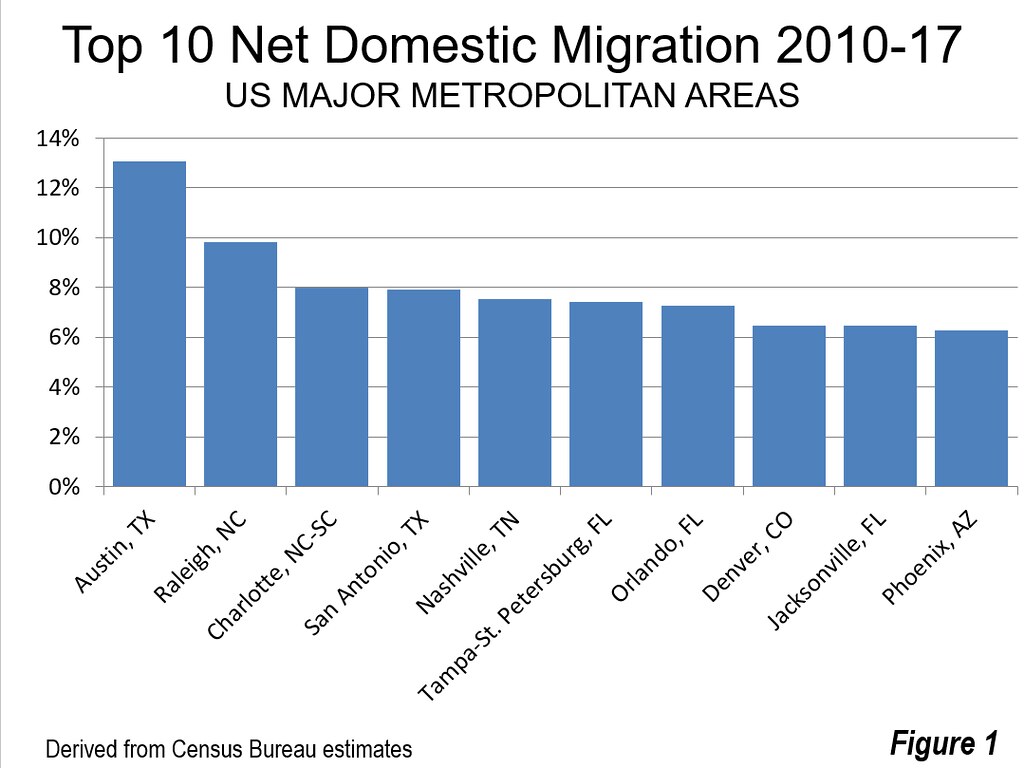

Proportionally, Nashville’s performance has been even more impressive. Only four metropolitan areas have gained more domestic migrants in relation to their 2010 population, Austin, Raleigh, Charlotte and San Antonio, with the latter two only slightly ahead of Nashville. Nashville’s net domestic migration rate was 20 percent greater than rapidly growing Phoenix (ranked 10th) and more than half greater than 13th ranked Portland (Figure 1).

Nashville’s Suburban Oriented Urban Form

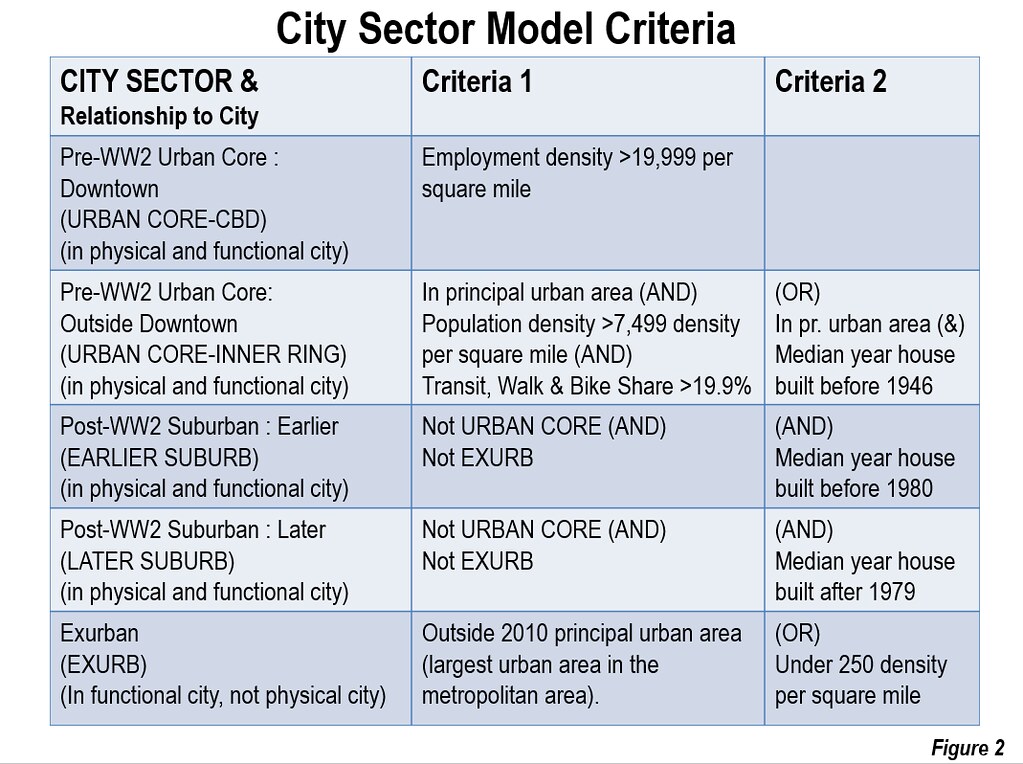

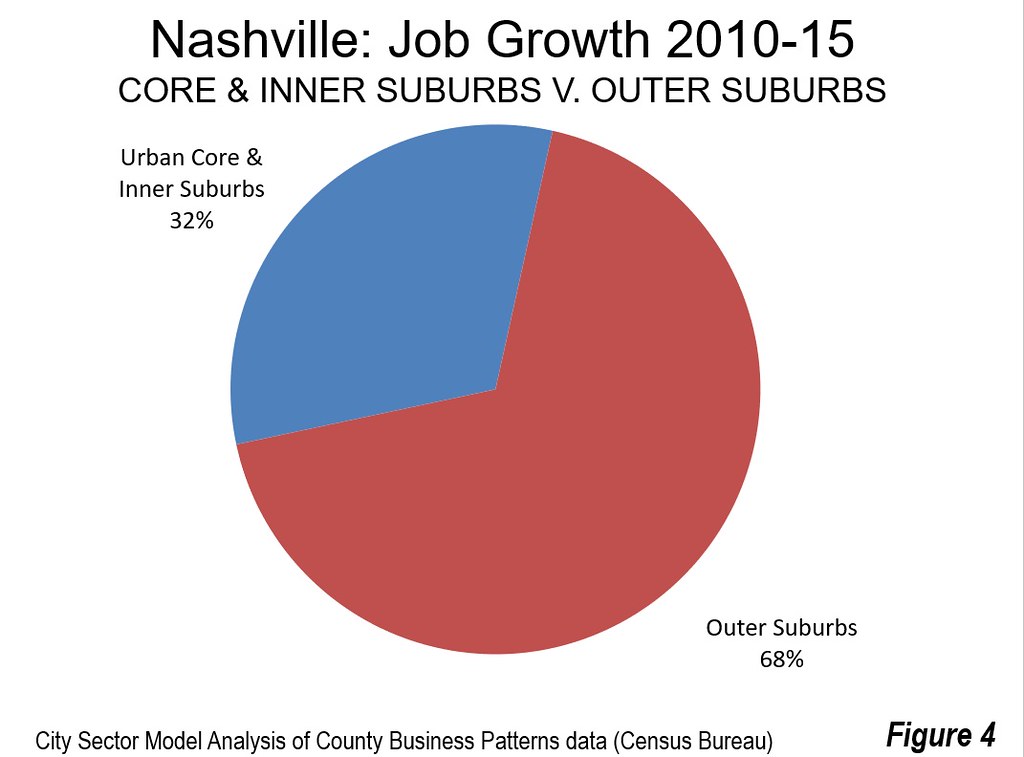

The problem facing transit planners is Nashville’s urban form, which mirrors that of virtually all 10 of the nation’s fastest growing metropolitan areas. Little of Nashville is urban core, by pre-World War II standards, with more than 95 percent of the population living in automobile oriented lower-density development, per the City Sector Model (Figure 2). A city sector model analysis indicates that 68 percent of the new jobs created in the metropolitan area from 2010 to 2015 were in later (outer ring) suburbs.

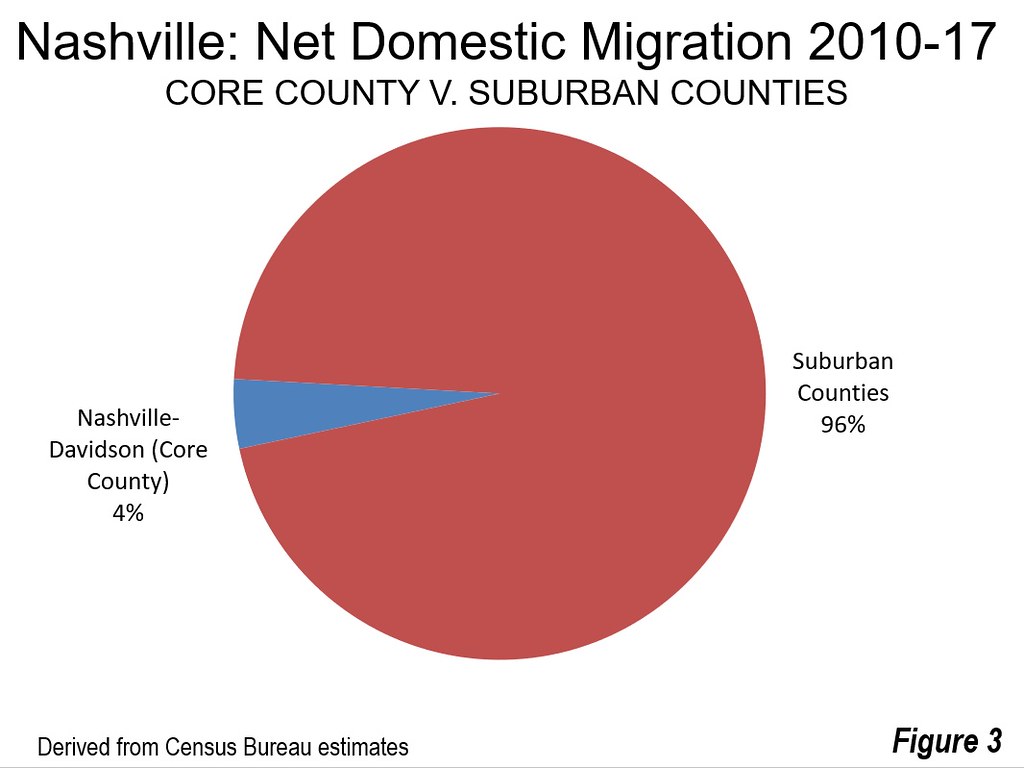

Like elsewhere in the nation, most people moving to Nashville are moving to the suburbs (see: “Moving Away from the Major Metropolitan Areas: 2017 Estimates”). The core county, Davidson County (Nashville has a consolidated county-core city government, see Note below) gained 5,300 net domestic migrants between 2010 and 2017. By contrast, the suburban counties gained 120,800 net domestic migrants, nearly 25 times as many (Figure 3).

Planning for a Nashville that Never Was and Will Never Be

One might expect that local leaders are busy planning for this expanding population. Voters in the city of Nashville (which is consolidated with Davidson County), are being asked to fund the same obsolete, and costly 19th century rail strategies that presume everyone works downtown. Profoundly miscast to serve the modern metropolitan area, America’s many new urban rail systems have simply not attracted net drivers from cars. According to Aaron Renn of the Manhattan Institute, rail makes sense only in the six metropolitan areas with transit legacy cities (See: “Does America Need More Urban Rail Transit?”).

It is hard to imagine a more inappropriate transportation system for Nashville. Transit carries less than one percent of work trips in the metropolitan area, less than one-fifth the national average (which includes areas that don’t even have transit). Out of the 53 major metropolitan areas (over 1,000,000 population), Nashville ranks 49th in transit work trip market share, ranking with other domestic migrant centers Tampa-St. Petersburg, Charlotte and Raleigh (Figure 4).

Most Nashville residents rely on contemporary, rather than obsolete, technologies for their mobility. Driving alone dominates mobility in Nashville, as it does in virtually all US major metropolitan areas. In 2016, 81.8 percent of work trips were by solo drivers, the 12th highest figure among the 53 major metropolitan areas. At the same time, Nashville’s drive alone share is fairly close to the major metropolitan median (middle value), which is 79.4 percent. It is not hard to imagine why Americans drive alone --- it provides the by far the fastest travel times and maximizes leisure time.

But there’s a way of commuting that conserves time even more --- working at home. Nashville ranks 12th in the share of commuters who work at home, at 6.1 percent. This is a higher share of workers than ride transit in oft-cited transit examples Denver and Salt Lake City, and nearly as many as in Portland. A principal advantage is that working in home does reduce traffic volumes and also reduces greenhouse gas emissions, since it eliminates the traveling to work. This is done at virtually no cost to the driving public or to taxpayers. This is in contrast to transit operating costs, which have risen far more than justified by the economic fundamentals.

Vain Hopes

Proponents claim, predictably, that the system will reduce traffic congestion, speed up travel and provide greater connectivity. They say that the five route rail system will cost only $5.4 billion dollars (though they don’t say “only”). All of these are vain hopes.

It is hopeless to believe that rail transit will reduce traffic congestion in Nashville. That would require a significant decrease in the percentage of commuters driving alone and an astronomical increase in the percentage of commuters using transit. With transit carrying less than one percent of commuters, even doubling transit use (highly inconceivable) would not be able to keep up with the annual growth, which in the metropolitan area is 1.8 percent.

It is hopeless to believe that rail transit will improve average commute times. The average transit commute time is nearly twice the average automobile commute in Nashville and substantially exceeds that of driving alone in every major metropolitan area, according to Census Bureau data.

It is hopeless to believe that rail transit will improve connectivity throughout Nashville-Davidson County. Transit’s principal market is downtown. For travel that does not begin or end downtown, the transit system requires one to go downtown and transfer to another line to get to the ultimate destination. The resulting circuitous travel and the time waiting between trains or buses makes travel times on transit especially longer where transfers are required.

It is hopeless to believe that the system will cost only $5.4 billion. Seminal international research by Bent Flyvbjerg of Oxford University (United Kingdom), Nils Bruzelius University of Stockholm and Werner Rothengatter of the University of Karlsruhe (Germany) in Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition shows that rail projects average 45 percent more expensive than promised, with cost overruns occurring in 90 percent of cases.

I speak from experience on this, having played a pivotal role in establishing the rail transit system in Los Angeles). By any measure, the Los Angeles rail system has been a profound failure. Now, with more than $15 billion in new rail lines operating, ridership is 20 percent below the peak 1985 bus-only level, while increasing taxes three times.

But from a cost perspective, Honolulu is far worse. Shortly after the tax to support the system was approved (2006), taxpayers were told that the cost would be $3 billion. The latest estimates are around $10 billion, and will probably rise further.

Nashville-Davidson: Poised to be the Most Costly System in History?

With that in mind, Nashville-Davidson voters could see the $5.4 billion project escalate to a final cost rising above $17 billion. This is particularly sobering, because on a per capita basis, the Honolulu project may have been the most expensive ever (the greatest tax burden). Worst case cost escalation (Honolulu rate) in Nashville-Davidson would result in even higher per-capita costs, because Nashville-Davidson has 300,000 fewer residents.

If the purpose of the Nashville-Davidson rail transit proposal is to spend taxpayer money, its success seems guaranteed. For the public, if misled by claims of traffic reduction, faster travel or improved connectivity, experience suggests success will be hopeless.

Note: The city-county government is called the “Nashville and Davidson County Metropolitan Government.” However, it is not a genuinely metropolitan government. Davidson County is only one county out of the 14 in the Nashville metropolitan area.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photograph: Seal of the Nashville and Davidson County Metropolitan Government

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Davidson_County,_Tennessee#/media/File:Sea...