NewGeography.com blogs

In December 2010, Meredith Whitney, the financial analyst, appeared on 60 Minutes, where she predicted that the United States would see between 50 and 100 defaults of municipal bonds. Since she was one of the earliest analysts to predict the financial meltdown, publishing a research report in October 2007 that said that because of mortgage losses Citigroup might have to cut its dividend, it was not surprising that her statement attracted a great deal of attention, but also significant pushback from industry representatives, who insisted that municipal bonds were safe. This book, "Fate of the States: The New Geography of American Prosperity" is her effort to elaborate on that call.

Whitney begins her analysis with a review of the housing bubble and banking crisis, which by now is well trod ground, but she does so in a highly informed and balanced way. Where some commentators want to place most of the blame on government, others on Wall Street, and yet others on the Federal Reserve Bank for keeping interest rates too low for too long, she argues that everyone behaved badly. The self-destructive behavior that she witnessed on the part of many banks and financial institutions during this period remains an enduring and puzzling part of the story.

Readers of New Geography will be familiar with two of the themes that she articulates. One is the rise of a zone of prosperity from the Gulf Coast through the heartland and up to North Dakota that has been built on pro-active energy policy and strong global demand for agricultural commodities. A second theme she articulates is the striking disparity in the cost of living between states like California and New Jersey compared with far more affordable states like Texas. Low cost states, she says, will continue to attract new investment and jobs.

In arguably the core section of the book, she explains how the housing bubble interacted with banking and government to create what she calls “The Negative Feedback Loop from Hell.” By way of background, it should be noted that the underlying economics of banking are unusual. As economist Joseph Stiglitz demonstrated in the 1980s, the price of money does not necessarily clear markets. Instead, banks often employ credit rationing in order to control risk. As she argues, this is exactly what happened in the states where the housing bubble inflated the most. These are the states where the subsequent economic decline was the greatest.

As Whitney shows, it was also these states, where government officials handed out the most generous pay packages, including large back loaded pensions. On top of that, these states often piled on the most government debt, which nearly doubled between 2000 and 2010. The result has been significant retrenchment on core government services, from police and fire protection to public education. In her view, this is the negative feedback loop from hell, and the reason that she believes that fiscal stress will continue for a long period of time.

As the fight for limited resources works itself out, she believes that besides government there will be three parties at the negotiating table. Two are straightforward enough: the bondholders, who expect to be paid back the money they lent, and the public sector employees, who expect to receive the pensions they were promised. But she also sees a third party. Writing shortly before the bankruptcy in Detroit, she presciently recognized that citizens will also have a claim on resources, arguing that they need and deserve the services that government is supposed to provide.

Although the sub title of the book mentions geography, Whitney largely dismisses what a contemporary textbook on economics and geography calls the “who, why, and where of the location of economic activity.” This is not surprising. There are probably few people who are aware that this branch of economics even exists. (Among professional economists, more attention has been paid in recent years with the advent of New Economic Geography as championed by Paul Krugman, although, ironically, empirical research indicates that key elements of of Krugman’s theoretical work are almost certainly wrong.)

While Whitney rightly focuses on the economic growth that distinguishes many of the states in the central corridor of the country, she cites data that shows that most economic activity continues to occur elsewhere. She observes, “These so-called flyover states contributed 25 percent of U.S. GDP in 2011, up from 23 percent in 1999.” That is nearly a 10 percent increase, but obviously from a lower base. A current and highly visible example of the importance of geography is the huge growth in the number of warehouses along the New Jersey Turnpike, as engineering projects deepen New York harbor and expand the Panama Canal. Access to water will always be important.

Additionally, I would argue that the issues that Whitney addresses cannot be fully understood without taking into account the challenges that continue to face older industrial cities. All economies must constantly re-invent themselves. In the case of cities with a large industrial legacy, however, intrinsic market failures caused by asymmetric and imperfect information have made redevelopment significantly more difficult. Theoretical and empirical work in recent years has also shown that joint and several liability under U.S. environmental law undermines efficient price discovery for properties that once had an industrial use.

These issues aside, Whitney has written a book that is both provocative and necessary. Clearly, certain states have instituted policies that are far more effective at attracting business and new residents. At the same time, other states appear unable to reform. Perhaps her central insight is that problems associated with debt can take on a life of their own. Therefore, her message is clear. States that properly manage their debt and pension obligations will enjoy a prosperous future. States that do not will encounter severe problems. Investors and public sector employees take note.

Eamon Moynihan is the Managing Director for Public Policy at EcoMax Holdings, a specialty finance company that focuses on the redevelopment of previously used properties.

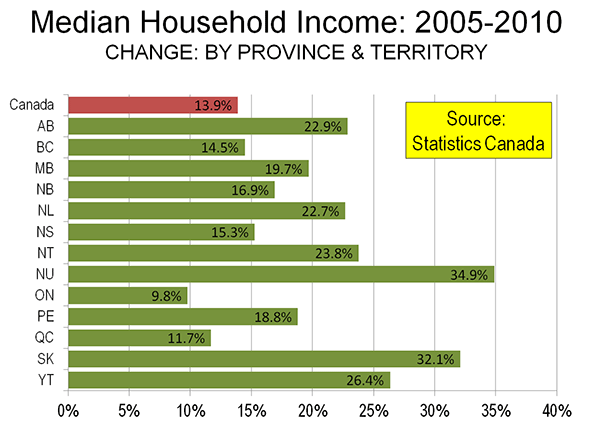

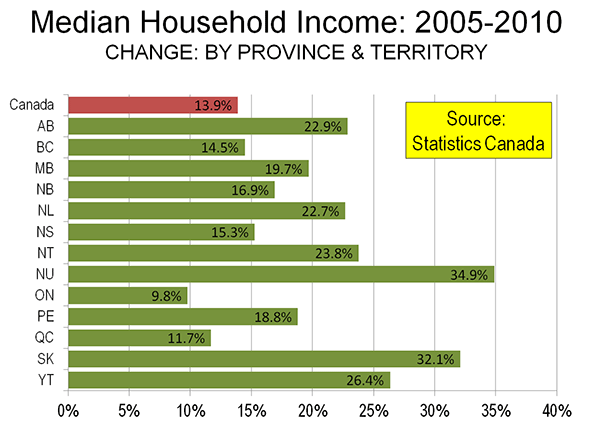

Statistics Canada’s newly released National Household Survey indicates changes in the distribution of median household incomes among the provinces and territories. The new data is for 2010, and indicates that an increase of 13.9 percent per household at the national level from the 2005 data collected in the 2006 census.

The big story, however, is the progress in parts of Canada that have grown used to laggard economic performance. In 2005, few would have expected the progress made in the provinces of Saskatchewan and Newfoundland & Labrador. In both cases, the resource boom had much to do with the turnaround.

Gains in Saskatchewan and the Prairies

Saskatchewan’s median household income grew 32.1 percent, out-distancing perennial champion Alberta and emerging Newfoundland & Labrador by nearly a third (Figure). Alberta’s income was up 22.9 percent, while Newfoundland & Labrador experienced a nearly as great 22.7 percent increase. Saskatchewan had trailed British Columbia by more than 10 percent five years before, but had edged ahead by 2010. Saskatchewan’s income level now leads all of the provinces except Alberta and Ontario.

All three of the Prairie Provinces did well. In addition to Saskatchewan and Alberta, household income in Manitoba grew at a 20 percent, stronger than all provinces outside the prairies except for Newfoundland & Labrador.

A New Day in Newfoundland and Labrador

While Saskatchewan has experienced prosperity from time to time in its history, the same is not so true in Newfoundland and Labrador. In fact, in 1933, the government of Newfoundland (as it was then known) voted itself out of existence as a Dominion of the British Empire because of its serious financial difficulties. Effectively, the Dominion was relegated to the status of a British crown colony (like former Hong Kong). Newfoundland joined Canada as the 10th province in 1949. With that, representative government was restored, but Newfoundland always lagged behind (generally along with the Maritime provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island). In 2005, Newfoundland and Labrador ranked 10th out of the 10 provinces in median household income. By 2010, the ranking had improved to 7th.

The Prosperous Territories

The greatest income growth (35 percent) was in the territory of Nunavut, which was created by carving out the eastern portion of the Northwest Territories in 1999. Nunavut covers a land area about 1.3 times that of Alaska, but has only 30,000 residents (about the same as live in a square kilometer of Manhattan or Paris). The Yukon experienced a 26 percent increase, while the Northwest Territories had a 24 percent increase. The Yukon and the Northwest Territories had stronger income growth than all of the provinces, except Saskatchewan.

The Old Dynamos Trail

Meanwhile, the economic dynamo of the nation, Ontario experienced household income growth of less than 10 percent, nearly a third less than the national average, and less than one-third of Saskatchewan. Ontario is home to more than one-third of the national population. British Columbia, which has historically experienced strong economic growth, could muster only slightly above average household income growth (14.4 percent compared to the national 13.9 percent).

This may be a surprising headline to readers of The Wall Street Journal and the Washington Post, which reported virtually the opposite result in their August 19 editions. The stories, “Hip, Urban, Middle-Aged: Baby boomers are moving into trendy urban neighborhoods, but young residents aren't always thrilled,” by Nancy Keates in The Wall Street Journal and “With the kids gone, aging Baby Boomers opt for city life,” by Tara Barampour in the Washington Post reported on information from the real estate firm, Redfin (a link to the corrected Wall Street Journal story is below). Both stories reported virtually the same thing: that 1,000,000 baby boomers moved to within five miles of the city centers of the 50 largest cities between 2000 and 2010. Because these results appeared to be virtually the opposite of census results, I contacted both papers seeking corrections.

When pressed for more information, Redfin.com responded with a tweet indicating that: “We don't have a link to share or published study; Redfin did a special analysis of Census data at reporters' requests.”

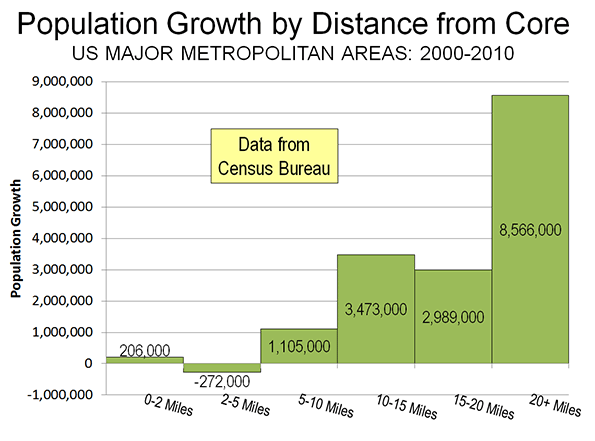

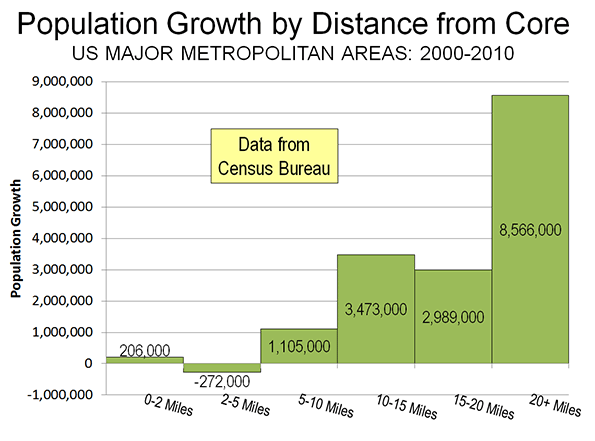

In fact, the census data shows virtually opposite. Redfin’s method was not clear, so I queried the five mile radius within the main downtown areas of the 51 metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 population in 2010, shown below in this table and figure.

Within the five mile radius of downtown, there was a net loss of 1,000,000 baby boomers, or 2 percent of the 2000 population (ages 35 to 55 in 2000). There was also a loss of 800,000 in the suburbs, or 17 percent of the 2000 population. The continuing dispersion of the nation is indicated by the fact that there was a gain of nearly 450,000 in this cohort outside the major metropolitan areas. Overall, there was a net loss of 1.3 million, principally due to deaths.

To its credit, The Wall Street Journal issued a correction, as I would have expected. The incorrect reference to an increase of baby boomers in the urban cores was removed. To my surprise, not only did the Washington Post fail to make a correction, but they also ignored multiple requests to deal with the issue (though my emails received courteous computer generated acknowledgements).

With the ongoing repetition of the “return to the city from the suburbs” myth, it is important to draw conclusions from the data, not from impressions.

An article by Nancy Keates in today’s The Wall Street Journal indicates that more than 1,000,000 baby boomers moved to within the downtowns of the 50 largest cities between 2000 and 2010. The article quoted Redfin.com as the source for the claim.

In fact, the authoritative source for such information is the United States Census. The Journal’s claim is at significant variance with Census data.

First of all, according to US Census Bureau data, the areas within 5 miles of the urban cores of the 51 metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 population lost 66,000 residents between 2000 and 2010 (See Flocking Elsewhere: The Downtown Growth Story). It is implausible for 1,000,000 boomers to have moved into areas that lost 66,000 residents (Figure).

Secondly rather than flock to the city, as the Journal insists, baby boomers continued to disperse away from core cities between 2000 and 2010, as is indicated by data from the two censuses. The share of boomers living in core cities declined 10 percent. This is the equivalent of a reduction of 1.2 million at the 2010 population level (Note). The share of the baby boomer population rose 0.5 percent in the suburbs, the equivalent of 175,000. Outside these major metropolitan areas, the share of baby boomers rose three percent, which is the equivalent of 1,050,000. All of the net increase in boomers , then, was in the suburbs or outside the major metropolitan areas, while all of the loss was in the core cities.

Among the 51 major metropolitan areas, only seven core cities gained baby boomers (See table at Demographia.). Among these seven, only two had larger percentage gains than the suburbs in the same metropolitan areas. One of these was Louisville, which accomplished the feat by a merger with Jefferson County. Louisville’s gain appears to have been simply the result of moving boundaries, not moving people.

Note: The age groups used are 35 to 55 in 2000 and 45 to 65 in 2010, which approximate the baby boomers. There was a decline in the number of baby boomers between 2000 and 2010 (largely due to deaths). The figures quoted in this article allocate the same percentage loss from this reduction to the 2000 baby boomer population for each core city and metropolitan area (the national rate).

by Anonymous 08/06/2013

When Rahm Emanuel was Barack Obama’s Chief of Staff, little did he know he’d be helping craft a law that would help him as the future Mayor of Chicago. Many American cities failed to put away enough money for current and former government workers. Rahm Emanuel and powerful Democratic Party interest groups would like the federal government to bailout their pensioners. While the unions are less shy about looting federal taxpayers, Emanuel is working hard getting federal help.

Emanuel needs to cut costs immediately to prevent more downgrades from the bond rating agencies. One of Emanuel’s creative financial techniques involves the use of Obamacare as way of pushing some financial costs from the city of Chicago budget onto the federal government. Many retired workers don’t like or want Obamacare. The Chicago Sun Times reports :

Chicago’s 30,000 retired city employees are trying to stop Mayor Rahm Emanuel from saving $108.7 million — by phasing out the city’s 55 percent subsidy for retiree health care and foisting Obamacare on them.

One week after an unprecedented, triple-drop in Chicago’s bond rating, retirees have filed a class-action lawsuit against the city and its four employee pension funds that threatens to make the financial crisis even worse.

The suit argues that the Illinois Constitution guarantees that municipal pension membership benefits are an “enforceable contractual relationship which may not be diminished or impaired.”

Chicago’s retired workers aren’t the only individuals unhappy with Obamacare. IRS workers don't want Obamacare but likely will find they can’t keep their current health insurance. All of this is providing massive strains on the Blue Model coalition of government workers and the Democratic Party. In Chicago, at least retired government workers can know who to blame for their change in health insurance if they lose their lawsuit. Mayor Rahm Emanuel not only was instrumental in getting Obamacare passed but now he’s dumping Obamacare on thousands of workers as Chicago’s Chief Executive.

|